Emperor Nobuhito and King Vittorio Emmanuele III of Italy.

Emperor Nobuhito and King Vittorio Emmanuele III of Italy.The new Emperor was Prince Nobuhito; inexperienced with regards to the administration of the nation but with a thorough background in the runnings of the navy. He had served as an officer in the Navy and had risen to the rank of Captain; he had even spent two years as the commanding officer of the cruiser

Yoshino. He was a personal friend to F.D. Roosevelt, having been introduced to him since before the Uchida-Roosevelt Pact, and a firm supporter of the re-establishment of the USA-Japanese relations. For now, however, he had a war to deal with, something for which he was uniquely qualified among the sons of the late Emperor Taishou.

A war that would be like no other. For circumstances were truly exceptional:

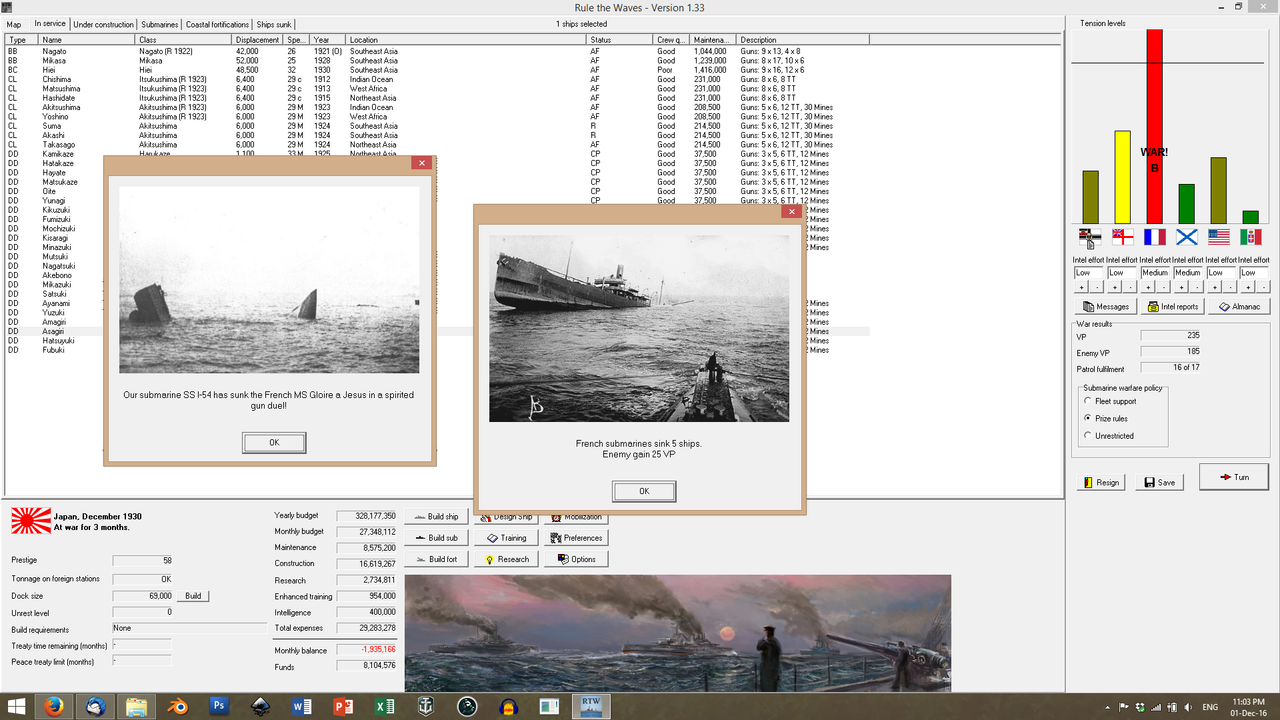

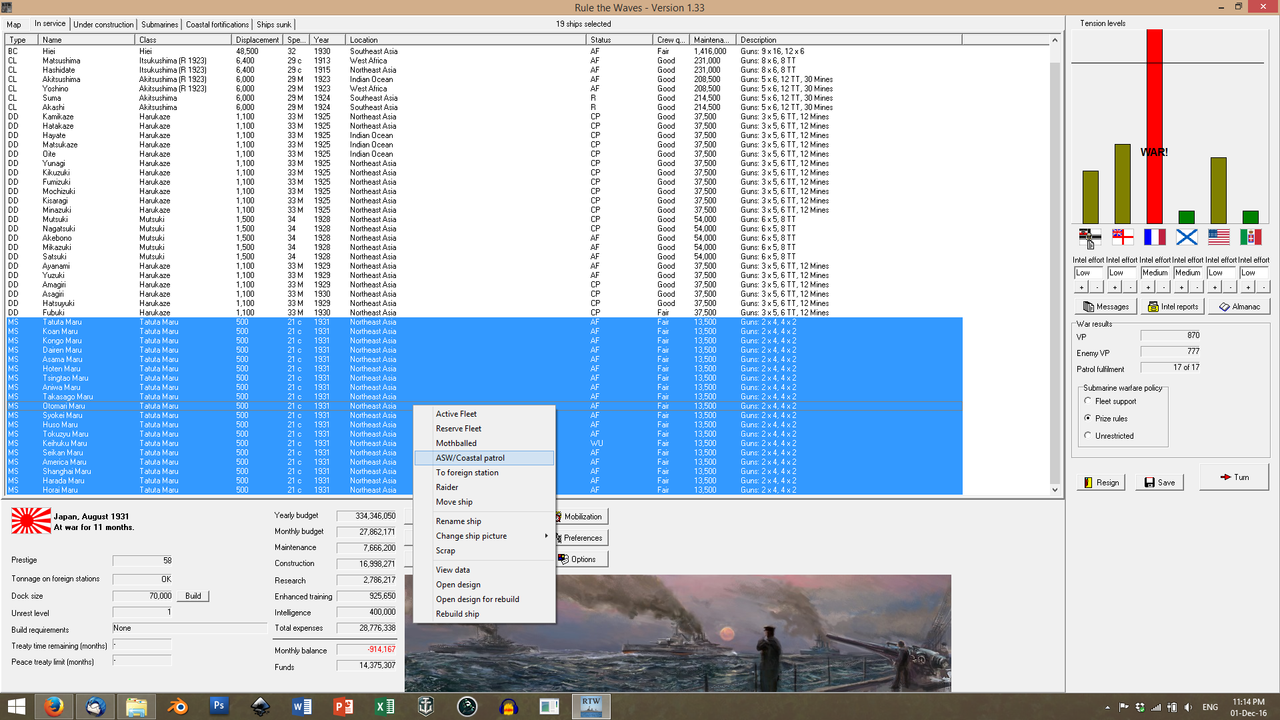

For one thing, the war could not have come at a worse time for the Japanese 'Maru boys'. The old minesweeper fleet was falling apart, not having been maintained to the proscribed levels during the final years of Hirohito's reign - funds had been shifted to capital ship production, leaving most of the minesweepers rotting in their moorings. Upon inspecting the navy, the new Emperor was horrified to discover this situation; he ordered all of the remaining derelicts to be scrapped for a pittance and initiated construction of a larger class of modern minesweepers for the 'Maru boys'. The earliest estimates would have the new ships leaving the slipways in ten months; until that time, the second-rate

Harukazes would take over ASW and Coastal patrol duties. Their mine rails (easily adaptable to depth charge munitions) would serve them well in this regard.

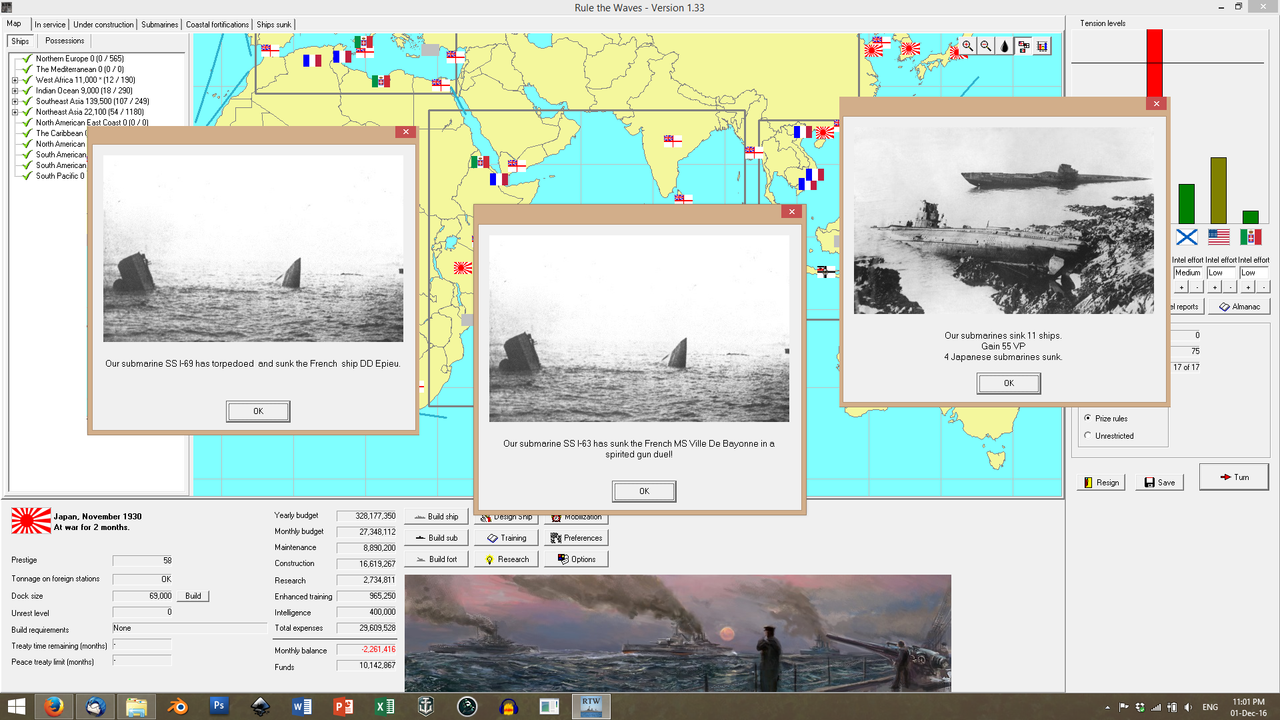

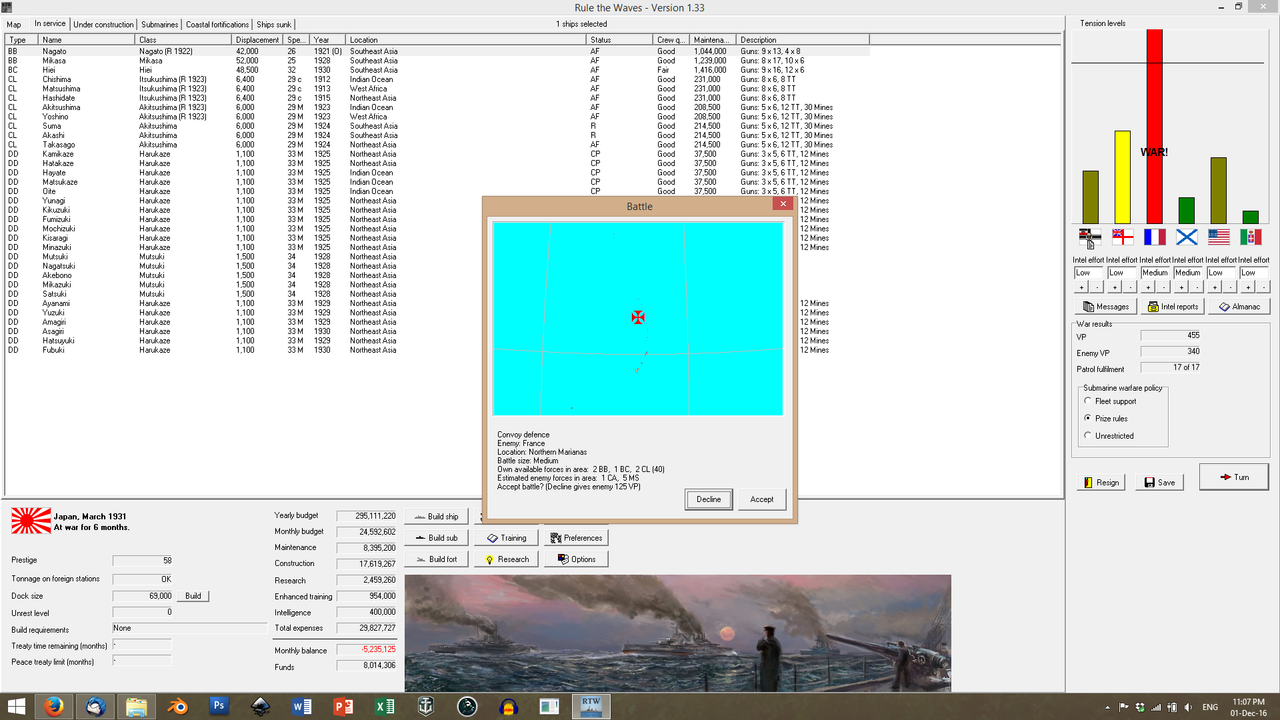

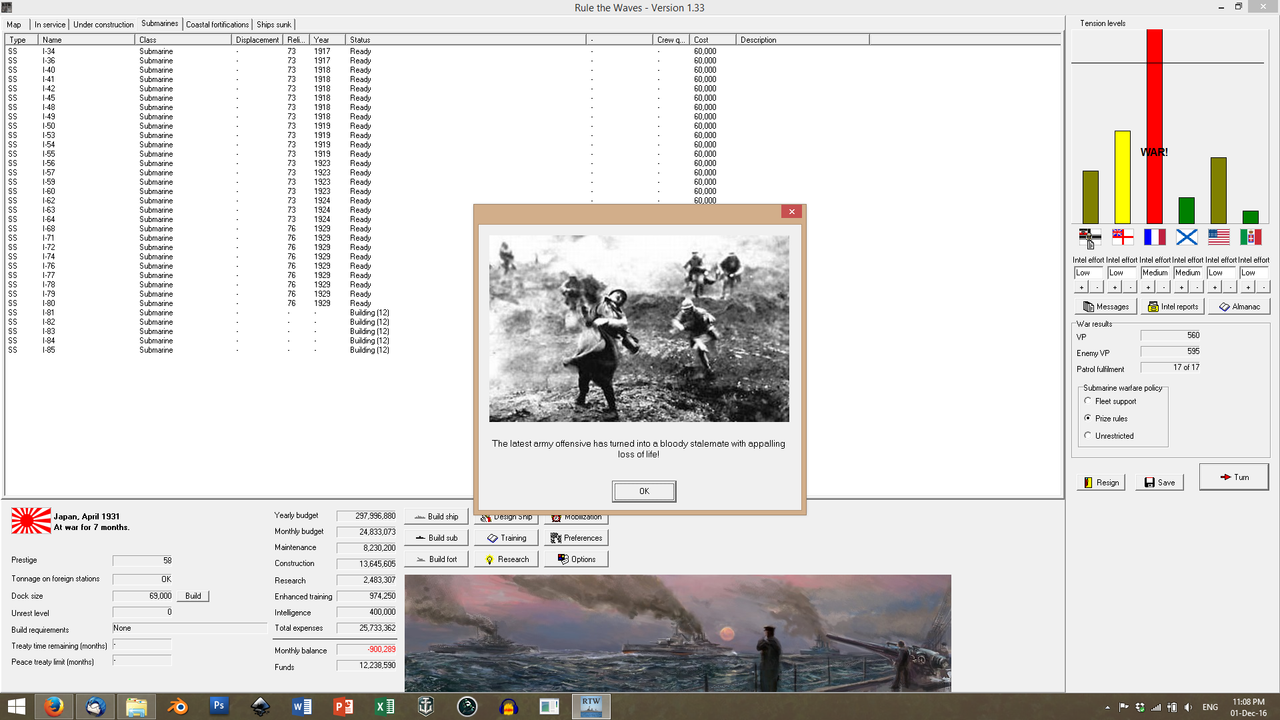

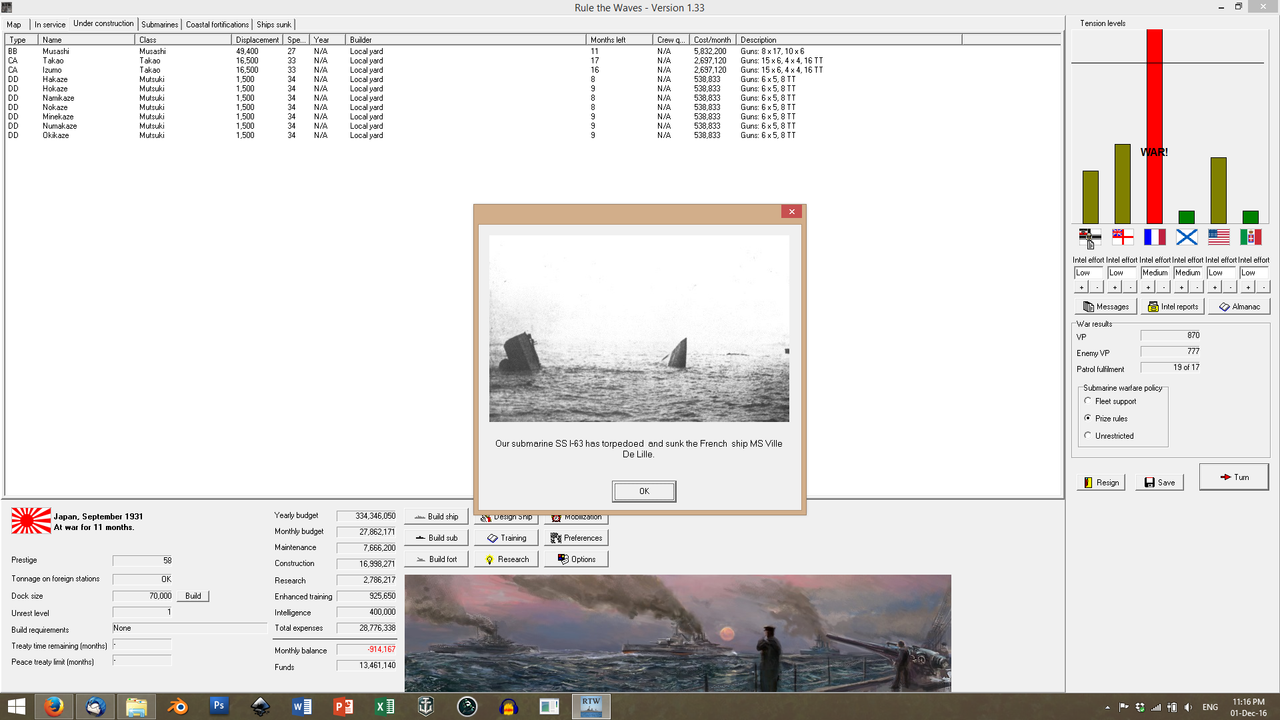

Furthermore, Japan had a greatly diminished battle-line, in number of hulls at least, compared to France. But Japan also had a massive and modern submarine fleet, that, with German support, could operate off German bases in Europe. The Silent Service received their orders, and its fourty subs left their moorings and headed for shipping lanes and enemy harbors like hungry sharks. For the first time in history, submarine wolfpacks went on the prowl.

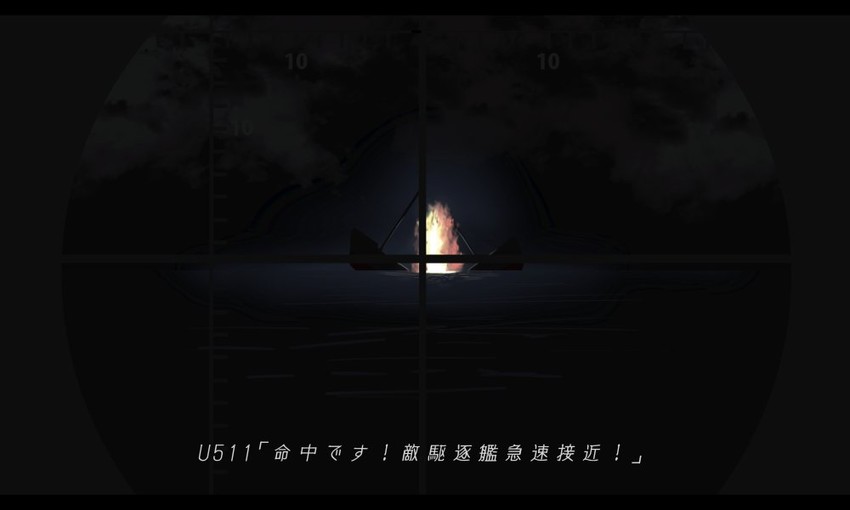

And did they ever earn their spurs. In the opening two months of the war, the Japanese submariners sent to the bottom two enemy minesweepers; a staggering quarter-million tons of merchant shipping were sunk. Even more spectacularly, Captain Biobaku of I-69 nailed a pursuing destroyer with a torpedo off the coast of Normandy. In exchange, the Japanese lost four submarines; a much lesser blow than what one would expect for such gains.

The savagery of the submarine attacks stunned the French Navy and sent the Marine Nationale ships scuttling back to their harbors. The Kriegsmarine pounced and used their capital ships to establish a blockade of the French ports; maritime traffic to and from France ground to a halt.

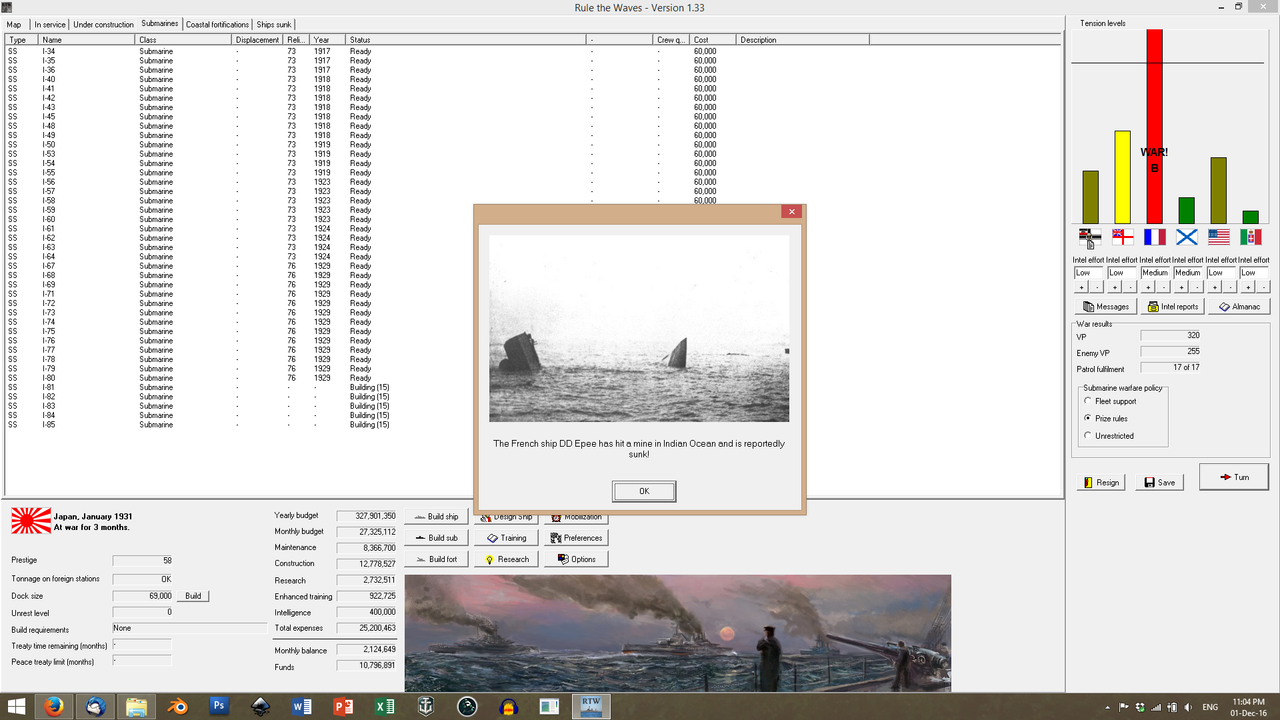

The

Harukaze minelayers claimed their own indirect victim in January, when a French destroyer was lost in the Indian Ocean...

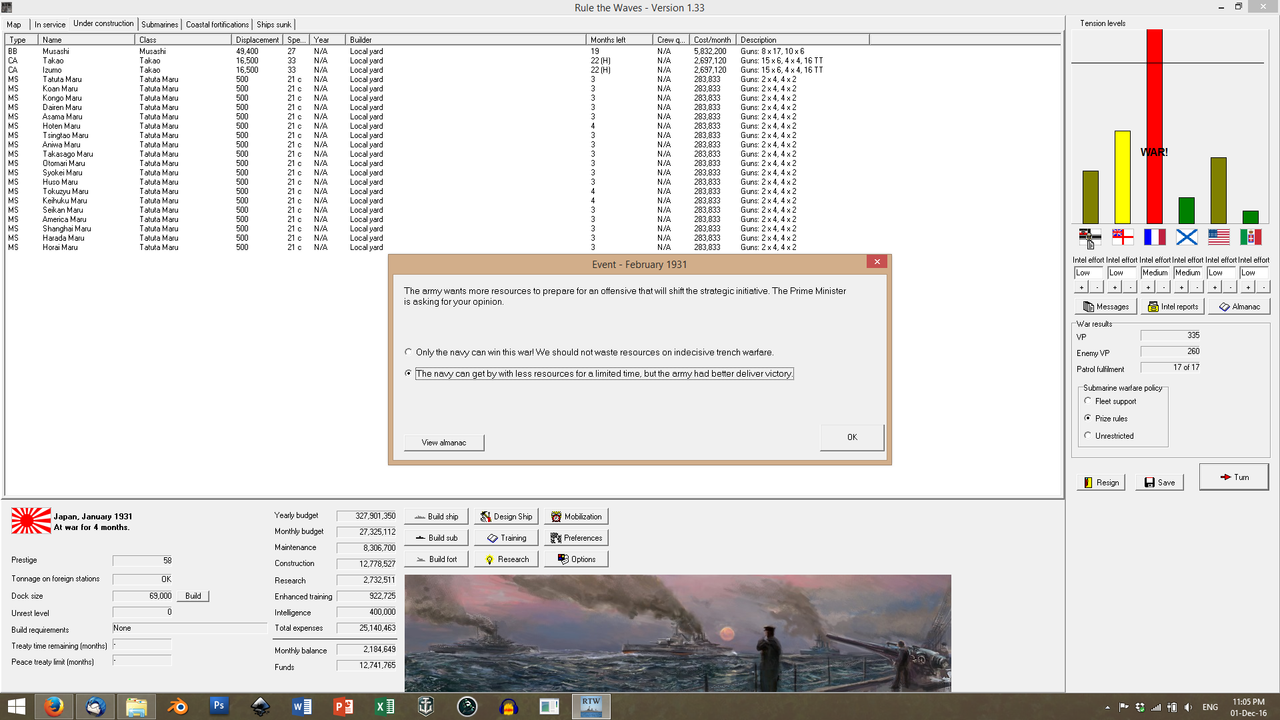

... and the Army started planning a massive assault against France's African holdings. The prize was thought to be Djibouti: the major French port in the southern end of the Red Sea. If that French colony could be conquered, France would lose her last resupply base in the Indian Ocean and Japan would gain a considerable degree of control over the traffic in the Red Sea.

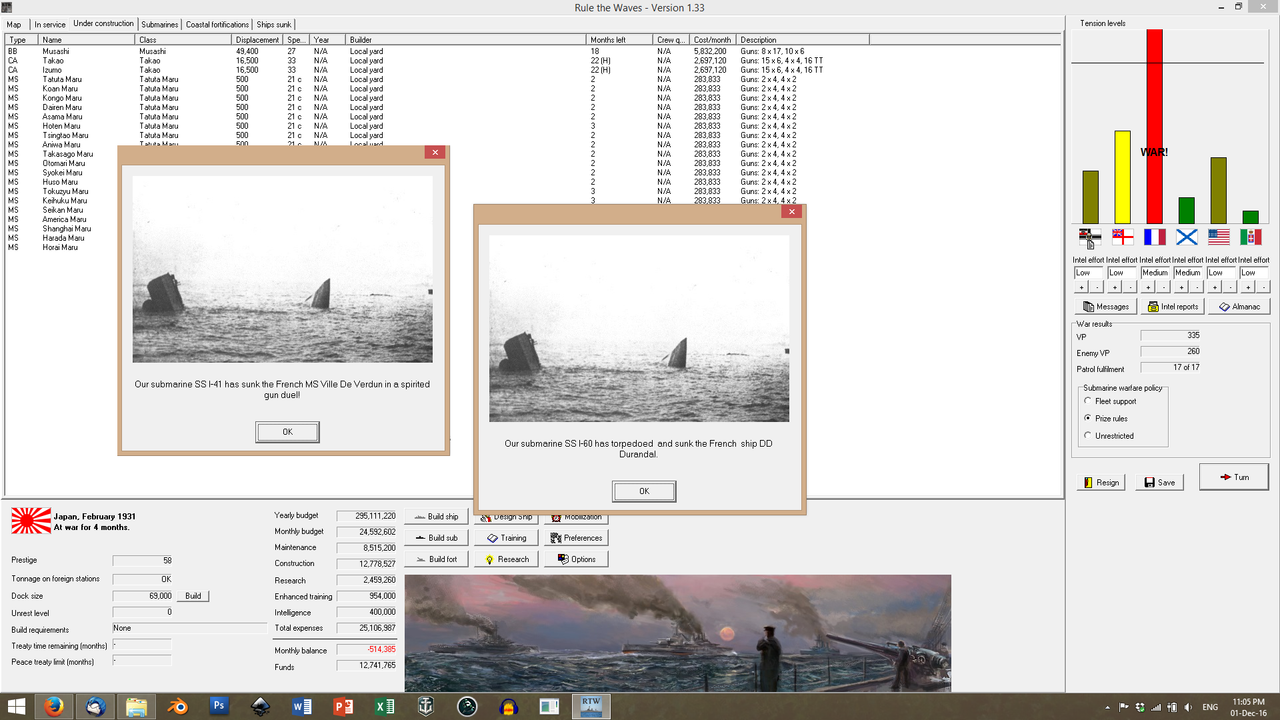

The Silent Service continued to make Japan proud. The German blockade meant that no merchant ships left the French Atlantic ports; but their minesweepers and destroyers were still out on patrols and it is on these ships that the submarines now turned their attention. Another minesweeper and the destroyer

Durandal were sunk off St Nazaire.

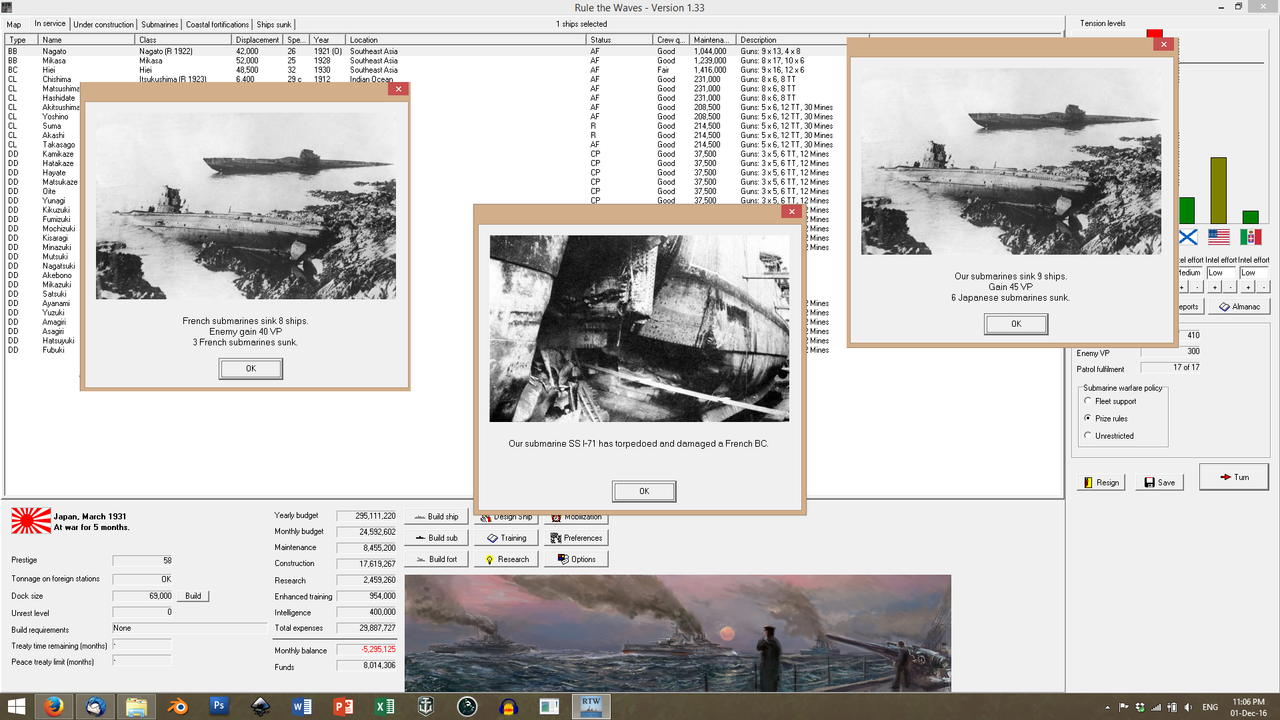

Unfortunately, by March, the initial shock of the submarine attacks had worn off and the French were gearing for a counterattack. A forey of French submarines gutted the convoy S-23, ferrying supplies from Sumatra to Madagascar; and Japanese submarine attacks on French ships in the Mediterranean were successful, but suffered heavy losses. Yet the Silent Service would still have the final word: on the 23rd of March, the Japanese submarine I-71 entered the port of Toulon almost casually during the dusk hours; sailed up to the moored French Battlecruiser

St Louis and scored two torpedo hits on her, from a distance of under 300 yards. The French ship went down in less than ten minutes but was successfully raised and repaired in five months; I-71 made good her escape, with her crew and Captain being hailed as heroes.

All was not good for the Japanese, however. The lack of dedicated minesweepers was tying down a large number of destroyers and that, in turn, was severely impacting the viability of the convoy routes in the Pacific. French subs and raiders operating from China could strike at Japanese shipping as far as Polynesia; not having enough ships for escort duty, the Japanese Admiralty had to cancel several supply convoys to the Marianas. The local populations had to endure considerable hardship during the time as necessary supplies never reached their destinations.

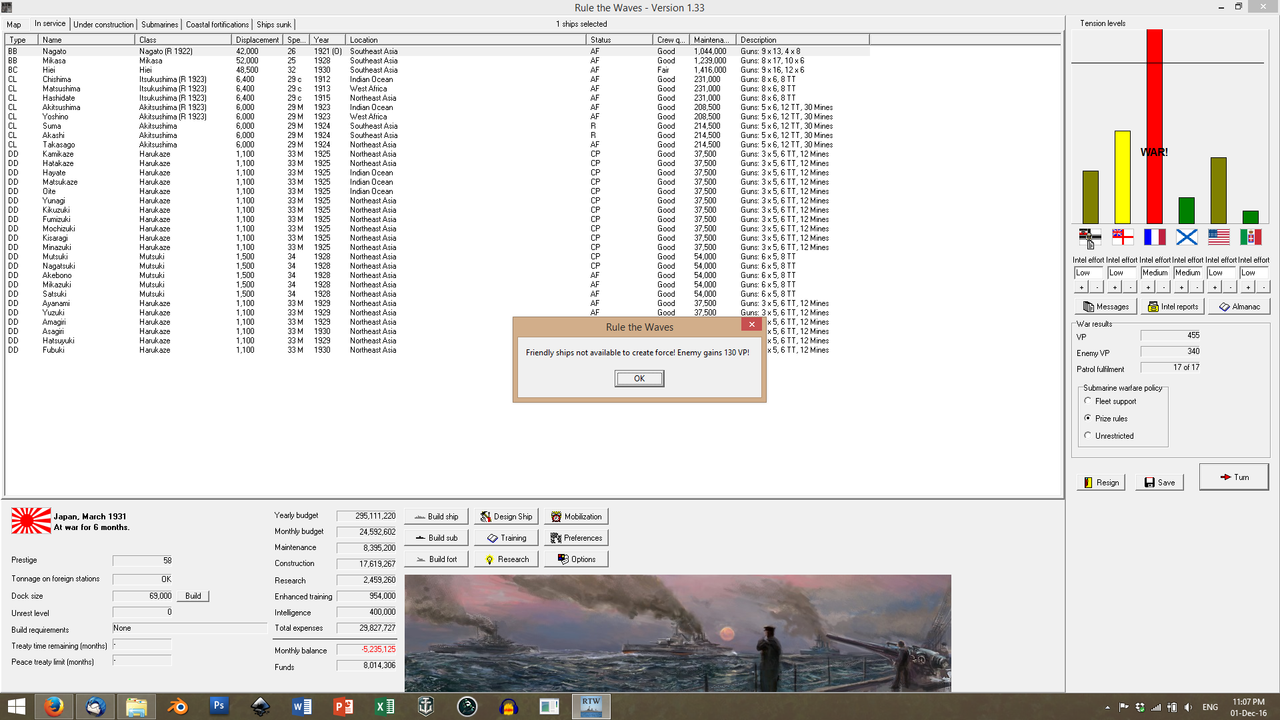

However, the Silent Service would not be deterred. In an almost comical repeat of I-71's achievement, Captain Iwaki of the I-64 led his boat on a raid to Brest, where he found the two French Dreadnoughts

Richelieu and

Temeraire at anchor. He fired the entirey of his torpedo complement at the latter of the two targets and scored three hits; the

Temeraire was only saved because the deck officer at the time ordered controlled counterflooding and called for tugboats to beach her on a nearby sandbank. The ship would stay out of commission for half a year.

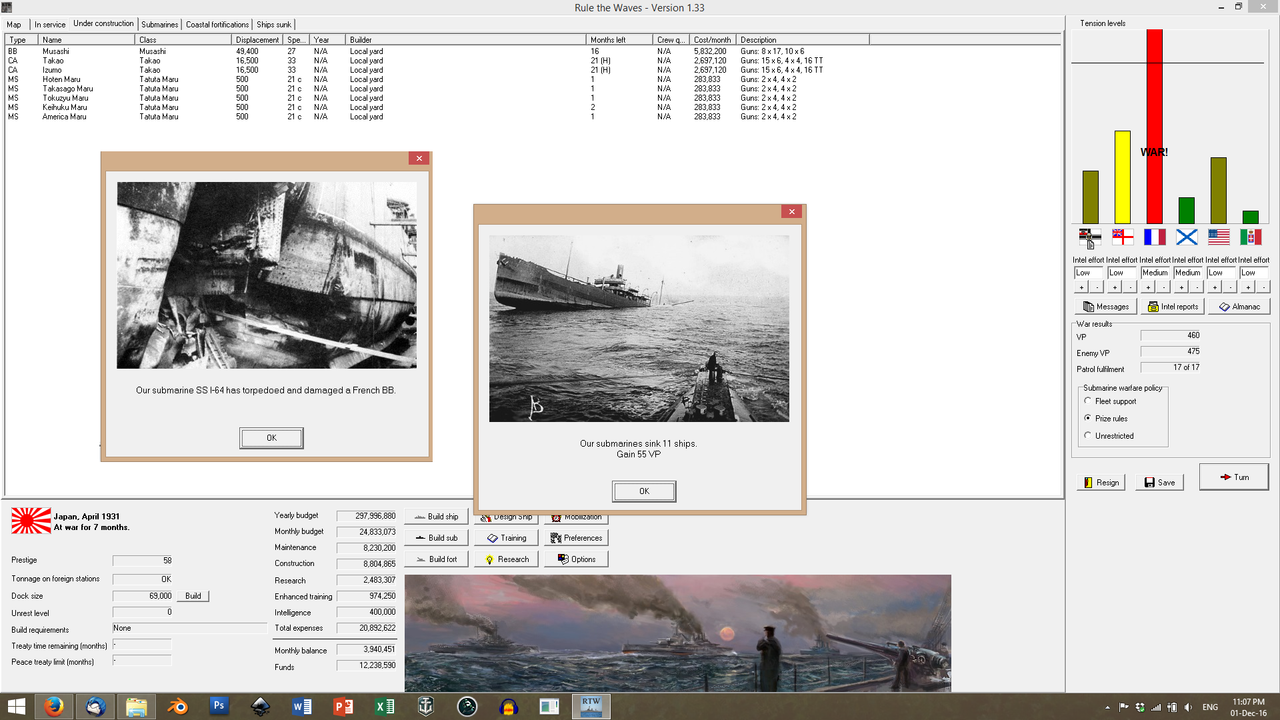

Unfortunately, the Army could not report similar success. Having put the Djibouti invasion on the backburner, the Japanese had to deal with several guerilla incursions of the French forces in their China holdings. A blood stalemate ensued, different yet no less horrifying than the trench warfare of earlier wars.

And in May, seven months into the war, the French submariners scored their first major success of the war. The

Chishima, the oldest surviving ship of the

Itsukushima class was torpedoed and sunk off the coast of Kamerun, in a heart-rending repeat of her sister's death.

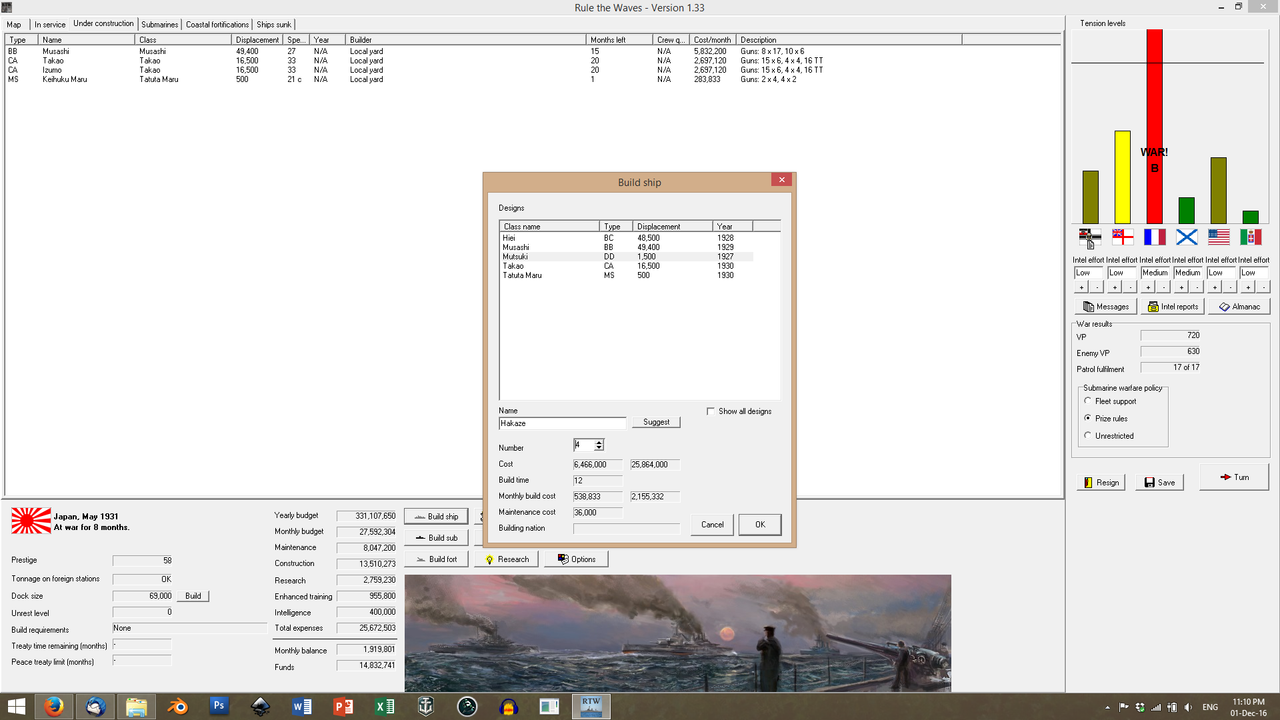

This spurred the Japanese to focus even harder on their light forces. The new minesweepers were complete and working up, the 'Maru boys' ecstatic at their new toys; the Admiralty immediately ordered four more

Mutsuki-class destroyers.

In June, the Japanese subs pulled back to friendly bases to resupply and repair, allowing the French a three-week lull. The French submariners poked, hesitantly, and scored almost thirty thousand tons in merchant tonnage sunk; then they got slapped down hard by the patrolling

Harukazes.

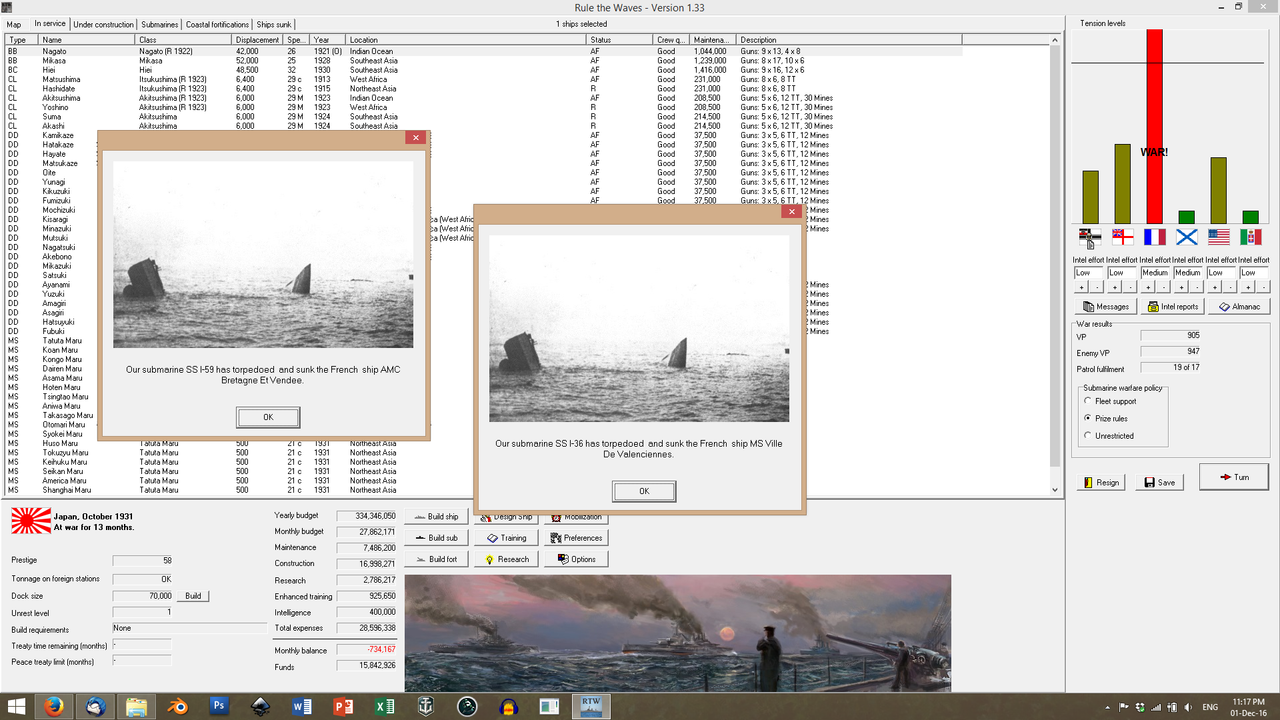

And then the Silent Service pushed back,

hard; I-59 and I-74, operating jointly from Heligoland

nailed two French destroyers that were patrolling the coast of Brittany.

And the 'Maru boys' finally reported their readiness to resume their duties and swarmed out of the Japanese anchorages, to relieve the

Harukaze crews.

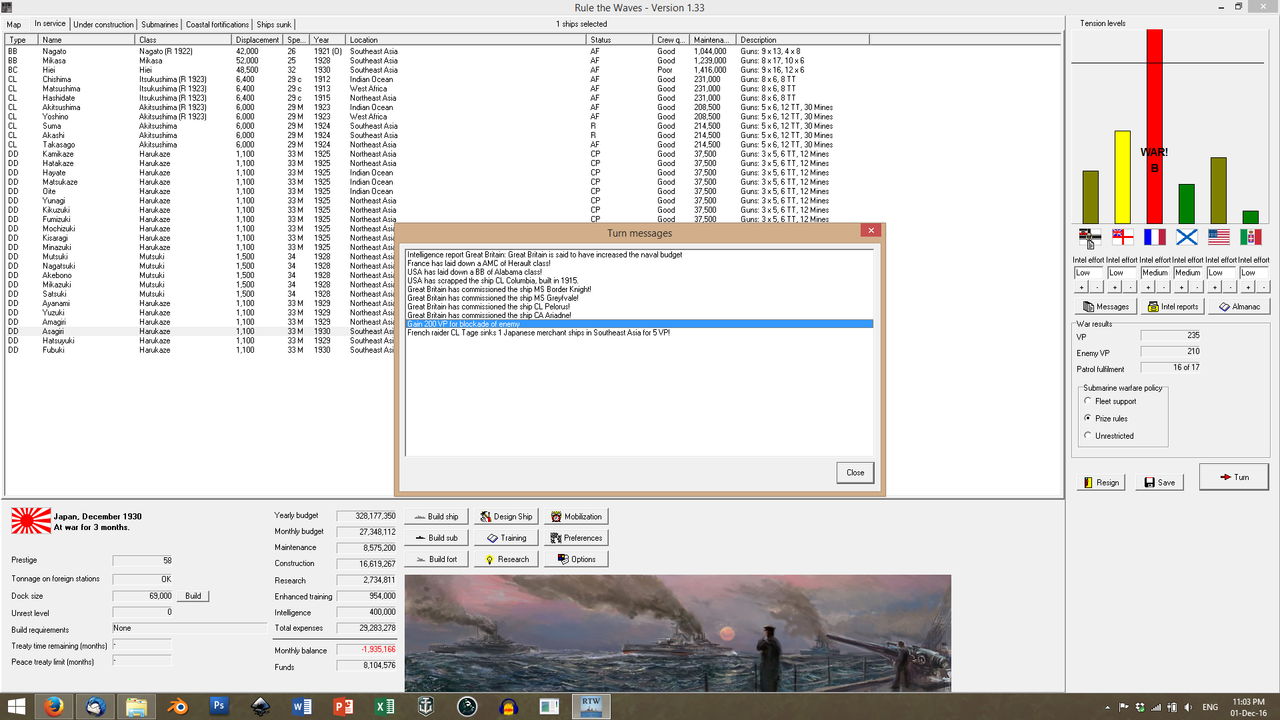

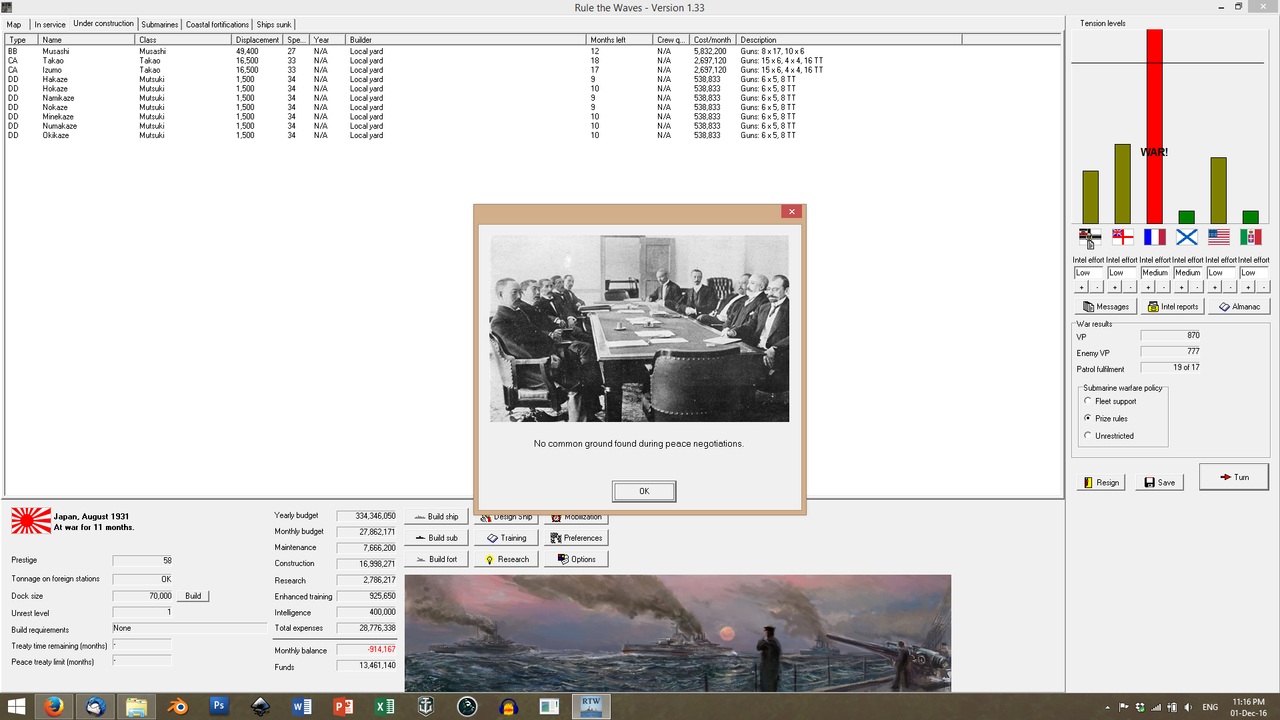

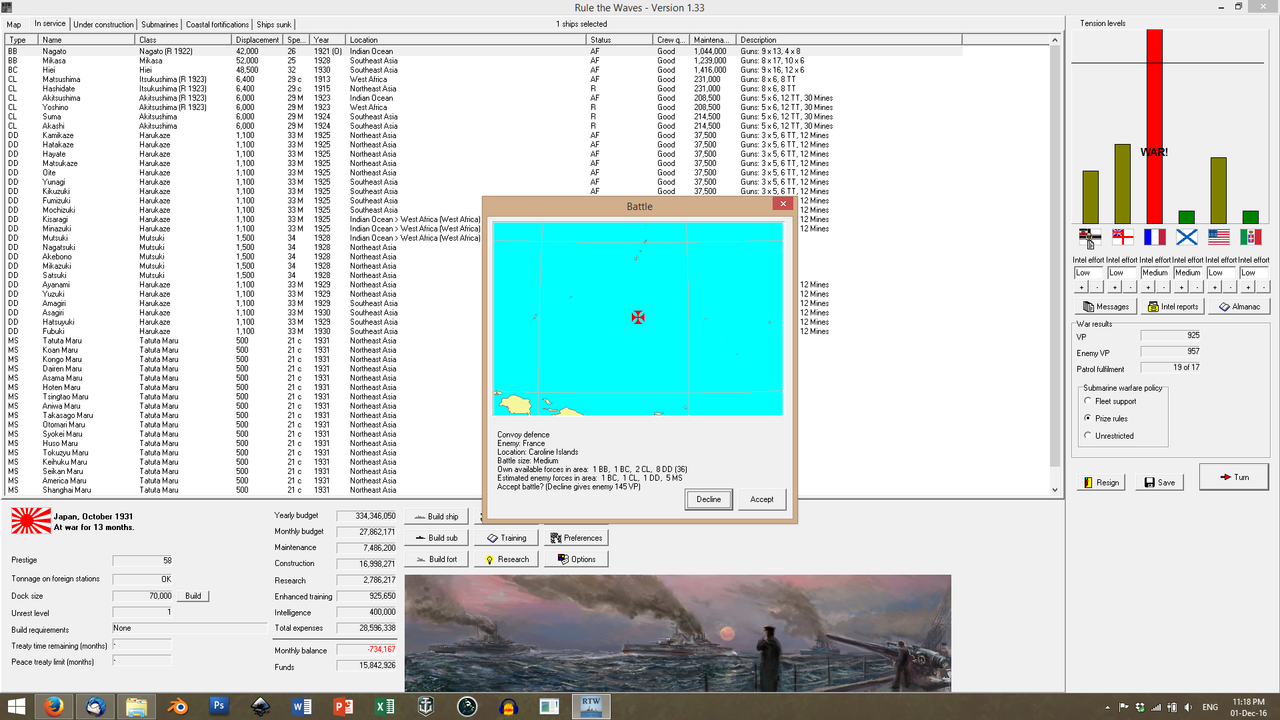

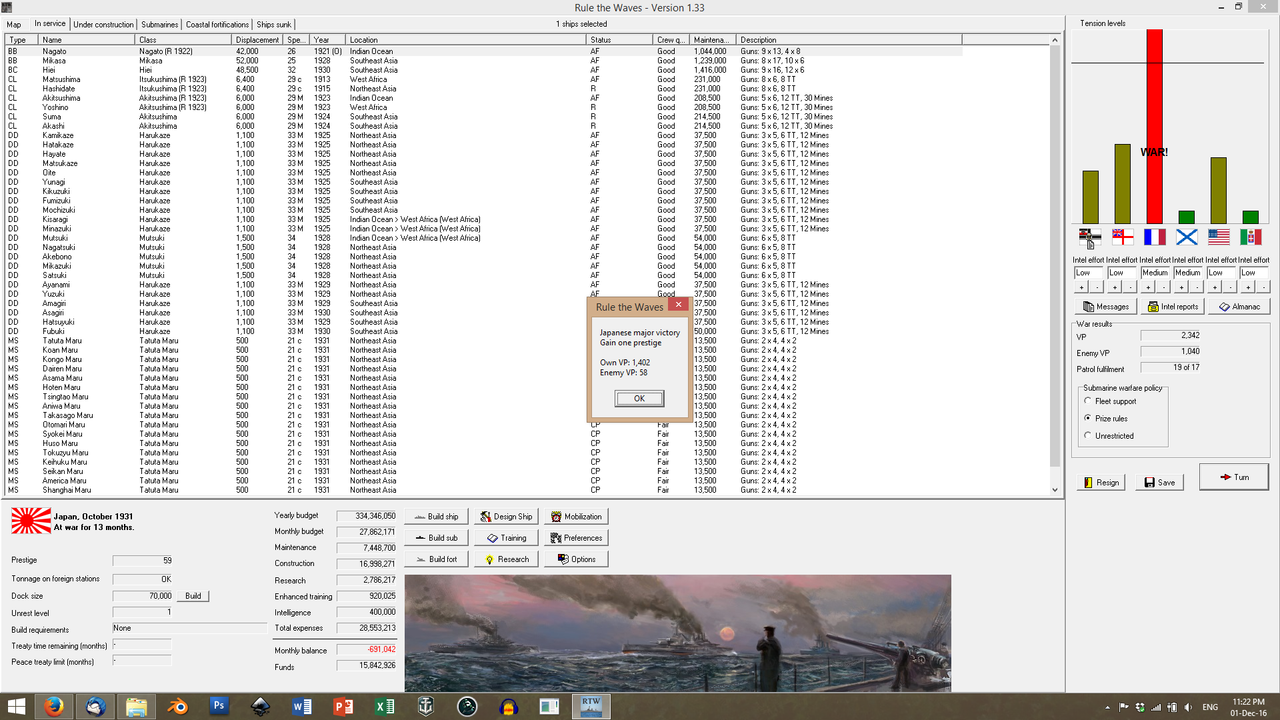

A year in and, despite attrition heavily favouring the Japanese, no noticeable progress was taking place. The French probed for a compromise peace, but only received a vehement response. This was not a posturing war, like the ones before - the Japanese were out for blood.

The Silent Service provided an eloquent punctuation for the Japanese official stance, by smashing two more French minesweepers and an armed merchant cruiser to kindling, inside the harbor of French Congo.

And

finally, there were enough light forces available to dispatch a convoy to the Alliance's much-suffering Pacific holdings. In a clear statement of how important the Japanese considered these territories, the Admiralty dispatched a task force of three destroyers and

Hiei itself as escorts to the convoy S-30.

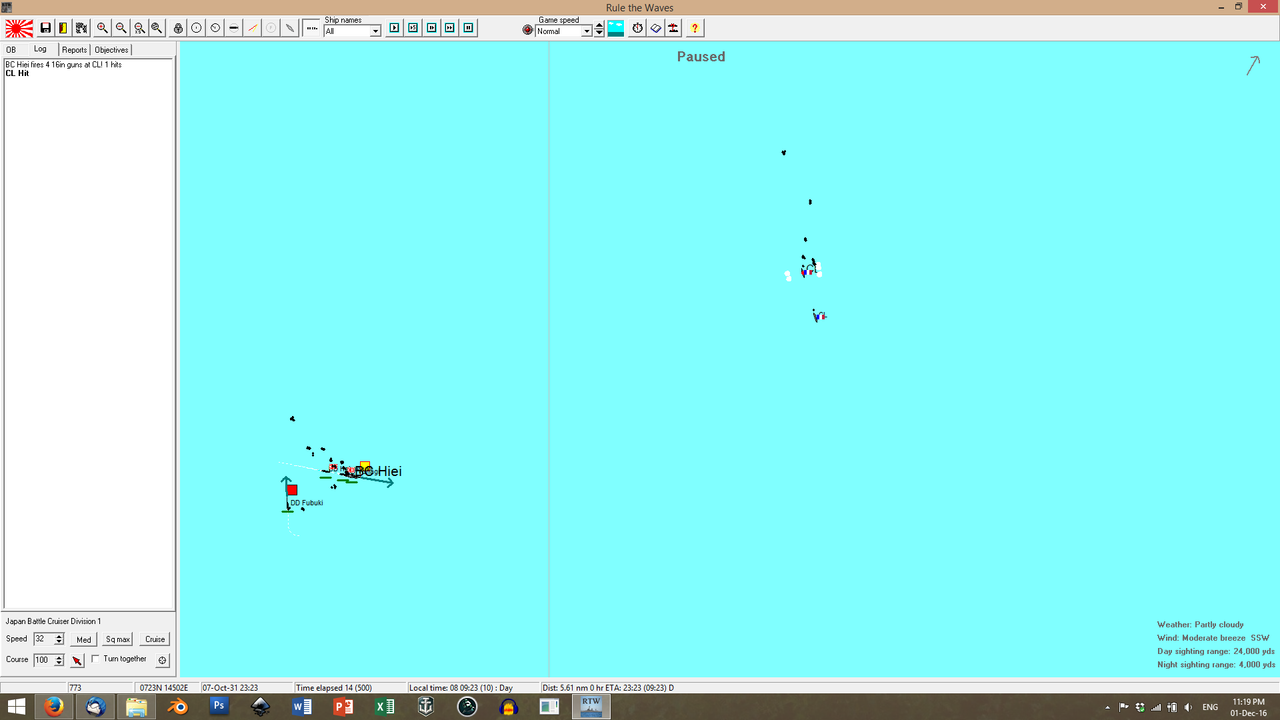

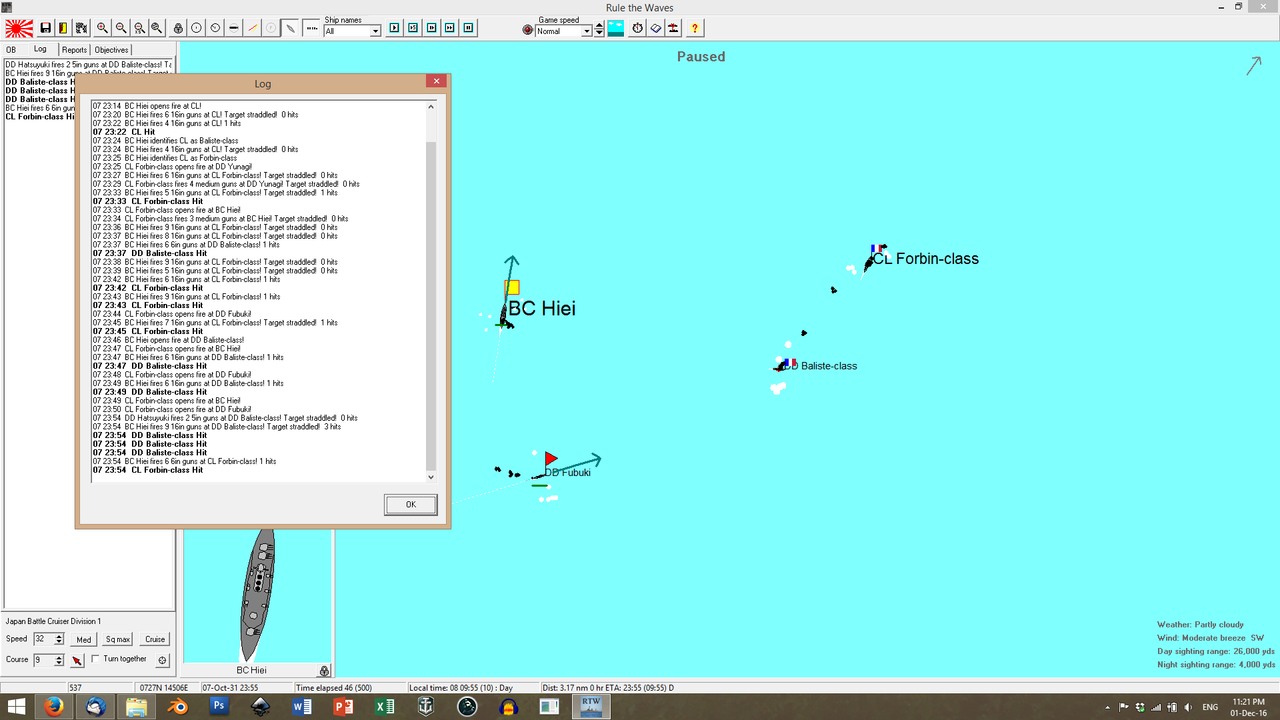

At 09:30, on the 7th of October, and while scouting ahead of the convoy, the

Hiei's ITMS spotted two ships closing in from the east; the signatures corresponded to light cruisers or destroyers.

Captain Yamamoto orders the main battery guns to open fire under ITMS guidance;

Hiei fires her first shot in anger from a range of around 18,000 yards. After a few corrections, her second salvo follows up, two minutes later. Her lookouts report an explosion on the second enemy ship and the bridge of the

Hiei erupts in cheers.

Encouraged by this success, Yamamoto orders full pursuit.

Hiei accellerates to her flank of 32 knots and turns toward the enemy, still keeping six of her nine 16-inchers pointed at the contacts. At close range, her lookouts identify the targets: a

Forbin-class raider and a

Balliste-class escorting destroyer: a development on the older

Catapulte-class. Nothing that could threaten the Japanese behemoth.

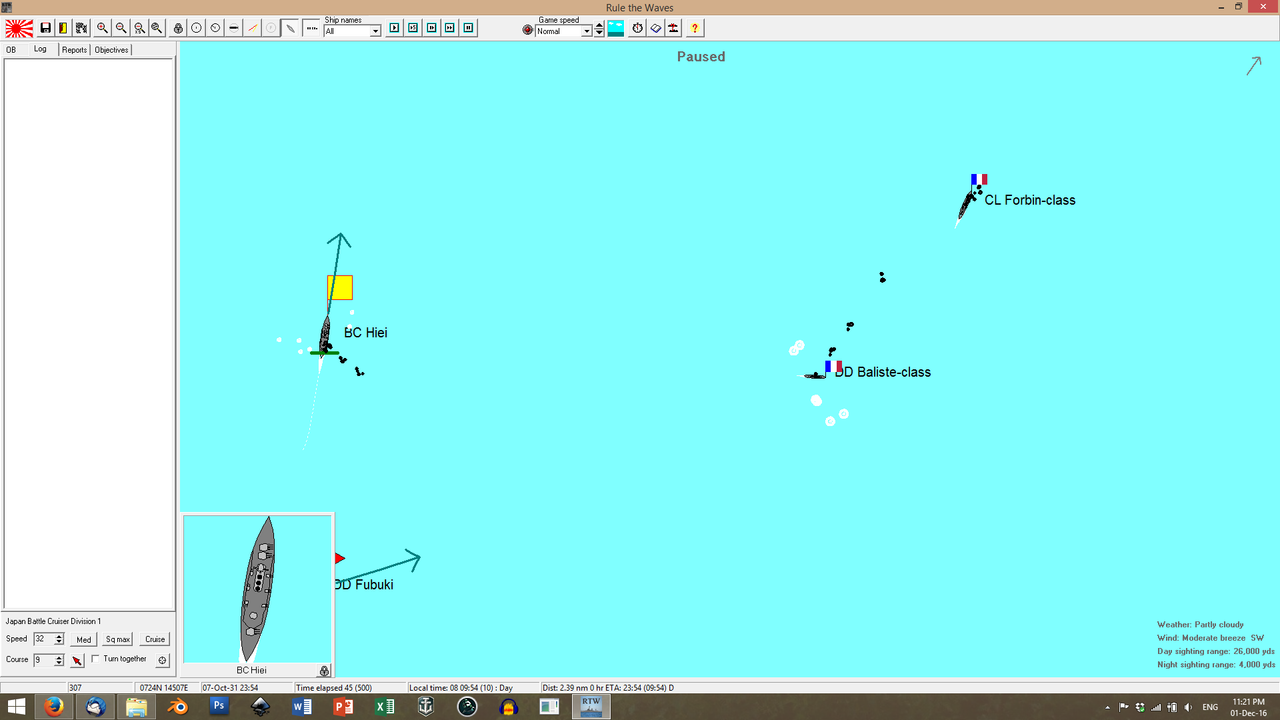

Hiei

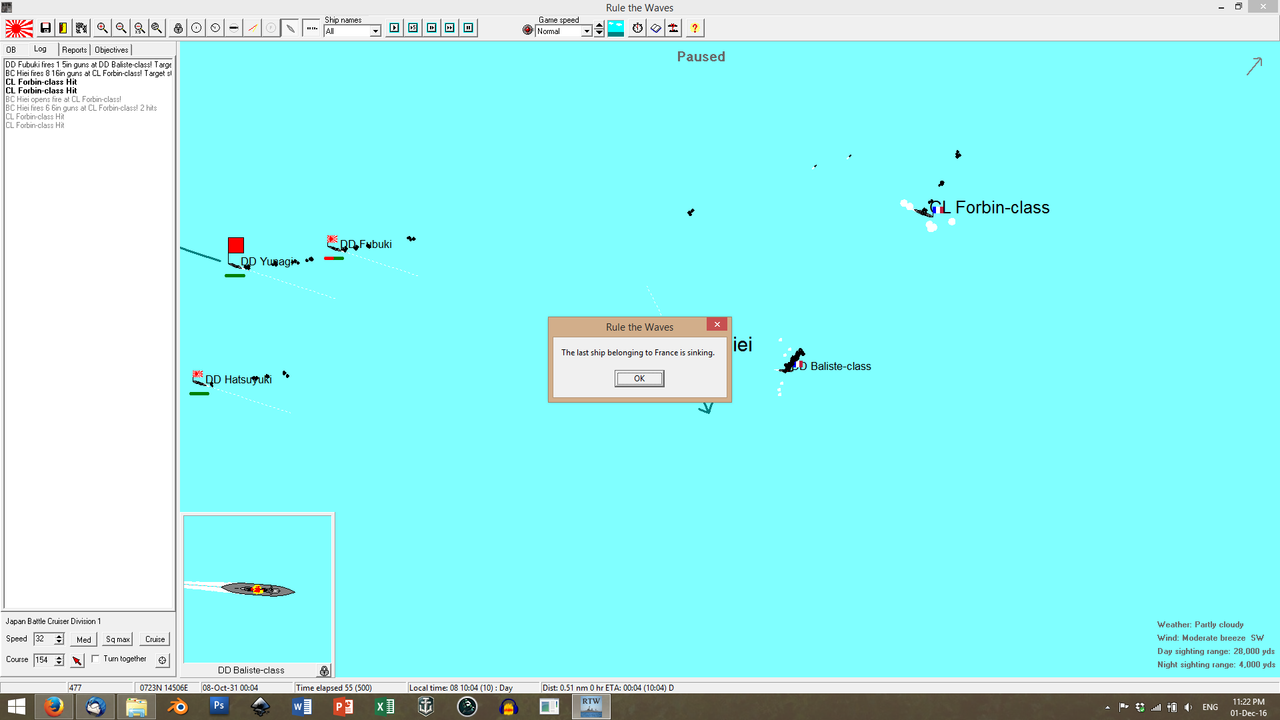

Hiei turns to bear North and unshadows her entire broadside. She proceeds to absolutely

savage the enemy ships. To add insult to injury, Yamamoto asks his targeting crews to test the ITMS systems further under combat conditions: he assigns the rapidly retreating

Balliste as a target and leaves the foundering

Forbin to

Hiei's secondaries.

Hiei's main batteries traverse; the ITMS reports that a targeting solution has been achieved; and, at 10,000 yards, the

Balliste is literally blown out of the water, under the impact of three superheavy High-Explosive shells. There were no survivors.

The

Hiei turns lazily to the South, to inspect the wreck; her main batteries train to take the

Forbin under fire. Two shells strike the French ship under the waterline and instantly snap her spine.

Hiei's destroyer escort pick up a few dozen survivors.

HON HON HON, BAGUETTES.

HON HON HON, BAGUETTES.