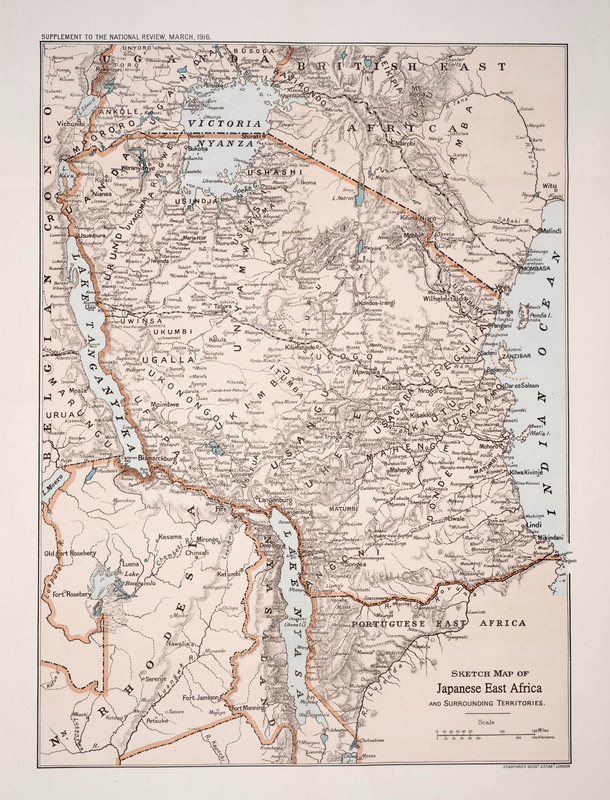

It was clear to the Japanese Government that her new colonial possessions had to be carefully managed, with the clear goal of becoming a true asset to the Alliance, instead of a millstone around their neck. Administrators, engineers, medical specialists, military consultants and prospectors had been dispatched to get an impression of what the Japanese had inherited from the Germans and to propose a plan of integrating what was now known as 'Japanese East Africa' into the Alliance.

In October 1913, the first detailed reports came in; the situation was both better and worse than expected.

The good news were that Japan had, without truly knowing it, acquired one of the richest and and most valuable areas in eastern Africa. The new territories stretched from the coasts of Tanzania to the great lakes of the African interior: Lake Victoria, Lake Tanganyika and Lake Nyasa. To the north, the entirety of the Serengeti with all its natural wealth, flora and fauna were now Japanese. The massive sisal- and rubber-tree plantations started by the Germans were ready to now supply the Alliance factories. And another surprise awaited the stunned Japanese topographers, something that

really spoke to their

Yamato-damashii.

In this far-off land, they had found Mt. Fuji's long-lost

onii-san.

When the first photographs were brought back to Japan and the representatives demonstrated their findings in a week-long conference in Kyoto, attended by the Alliance's elite, this was what forever banished any doubts that Japan had done well.

The bad news were that Germany, in its two decades of administration, had failed to make East Africa profitable. Every year, the colony had to be heavily subsidised by the German Government and it promised to be a similar weight to the Alliance's budget in the years to come.

More importantly, with the exception of economic returns, the Germans had perhaps done

too good a job. The local tribes had experienced the benefits of German medicine; German schooling; German technology and infrastructure. An extensive railway (partly still under construction and originally slotted to complete in 1914) connected the port of Tanga to the interior, as far as Lake Tanganyika and the commercial harbour of Tanga knew heavy traffic, despite its limited capacity to support a military fleet.

This made the locals rather hostile towards a regime change. The Alliance would have to, somehow, one-up the Germans in their own game, if they expected to truly establish themselves in the area.

It would be a long and difficult process, but the Alliance had two notable things to offer, which the Germans never could:

Firstly, (and surprisingly) a higher budget. The economy of Japan was still smaller in absolute numbers than that of the Germans - but it was a)

concentrated, with a larger percentage being available for colonial support, b) growing rapidly, thanks to trade and economic partnerships with the USA and other countries and c) supported by a large Alliance, eager to accept a new member into its midst. As an end result, the net amount that the Alliance was willing to pour into East Africa,

in the first year of their administraion alone, rivalled Germany's budget for the colony in the last three years

combined.

Secondly, (and that was the real deciding element in the long run), the Japanese had no interest in establishing a colony or protectorate along the European model. The goal of the East African Administration (東アフリカ政権 -

Higashiafurika seiken) was to guide the development of the region in such a way as to make it semi-autonomous, with an administration comprised almost entirely by natives within a projected timeframe of two decades; not unlike what was currently underway for Sumatra and Japan's Polynesian holdings.

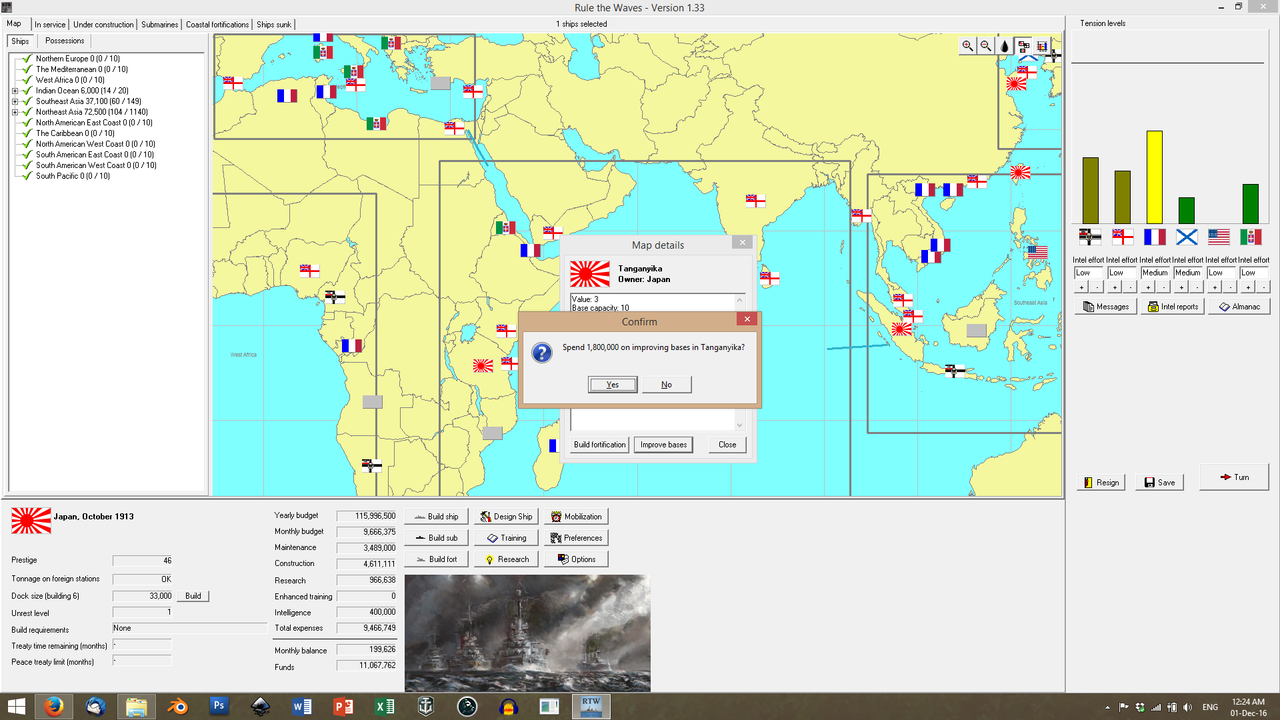

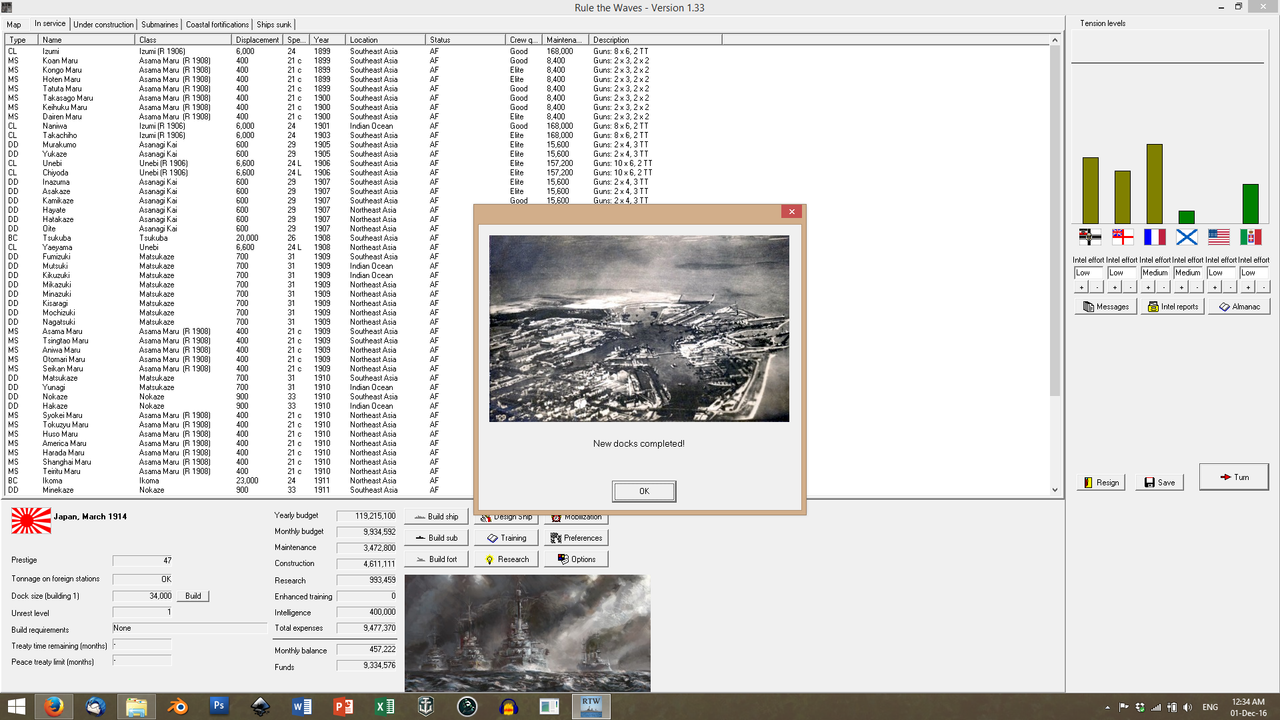

The Navy took up its own part of the burden, by spending a considerable sum of its monthly budget in dredging up and improving the military harbour installations of Tanga. They also deployed the veteran cruisers

Izumi and

Naniwa with a destroyer escort permanently on-station. Promising candidates and volunteers for crewmembers were selected among the native Askari (colonial) troops. The natives had, so far, been banned from naval service by the German authorities; this gesture of trust by the Japanese generated no little amount of goodwill. The already-multinational character of the crews also helped mitigate native hostility and created a true melting-pot environment.

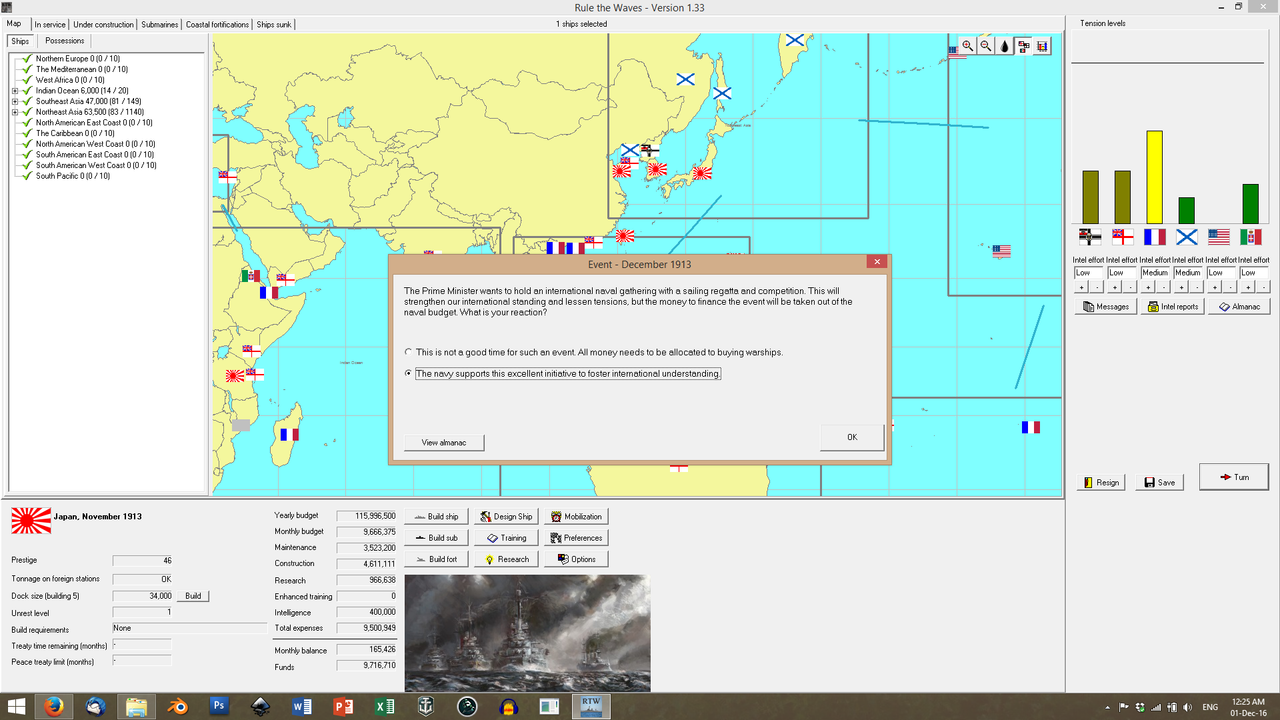

The Navy also took up the entirety of the expenses for the 1913 International Naval Gathering, held in Sasebo. The three-week gathering saw ships from every Power gather in Japan and included a regatta. It gave the diplomats time and opportunity to diplome and the Navy men the chance to sneak looks onto enemy ships. The Japanese Navy was happy to note that they were not falling behind.

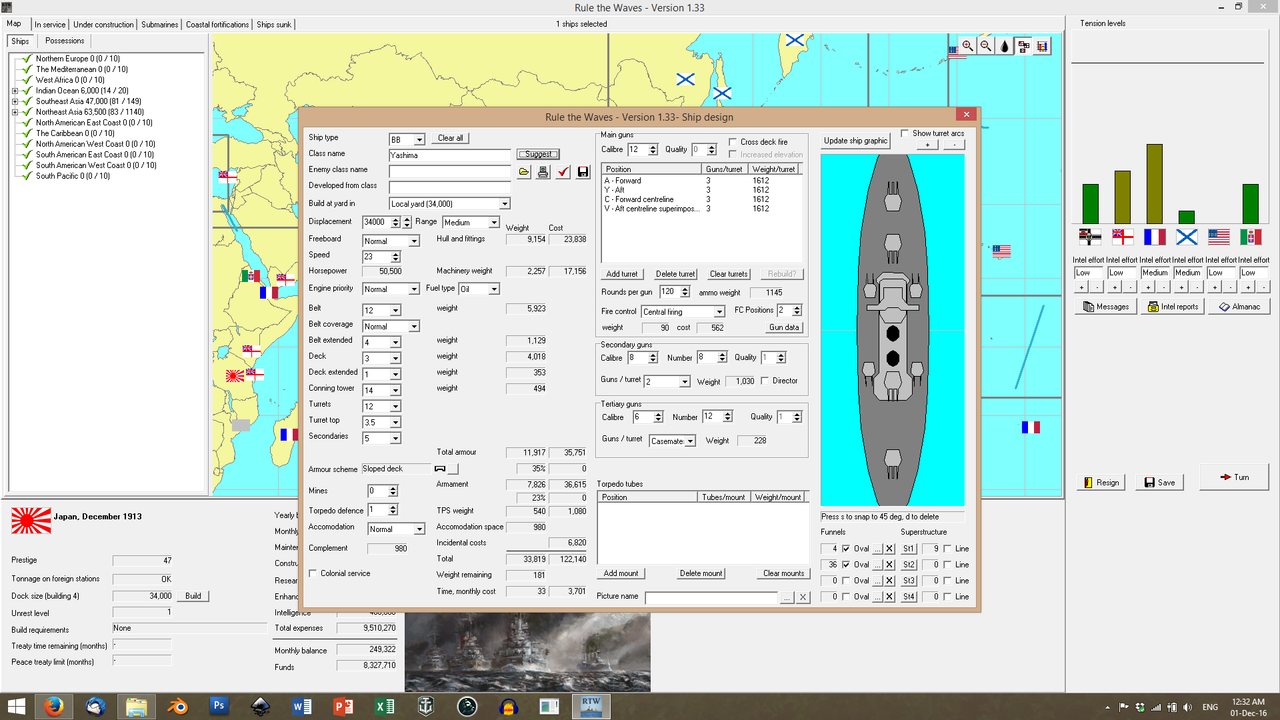

Yet there remained the problem of Japan's lack of Battleships. The

Yashima, a twelve-12'' monster was proposed but never built - lack of funds was a persistant problem for the Japanese.

The new year started with China approaching Japan for support. France had been making angry noises and casting meaningful looks towards the Hong Kong area. Japan covertly arranged for a three-way meeting with the English authorities and agreed to provide 4'' field artillery, based on naval gun designs, to her allies. France, eventually, backed off - but the event massively raised Japan's prestige among her Allies, was a boon for the Navy's budget and also left the English grimly satisfied and the French and Germans (oh so eager to see their rivals humiliated) seething.

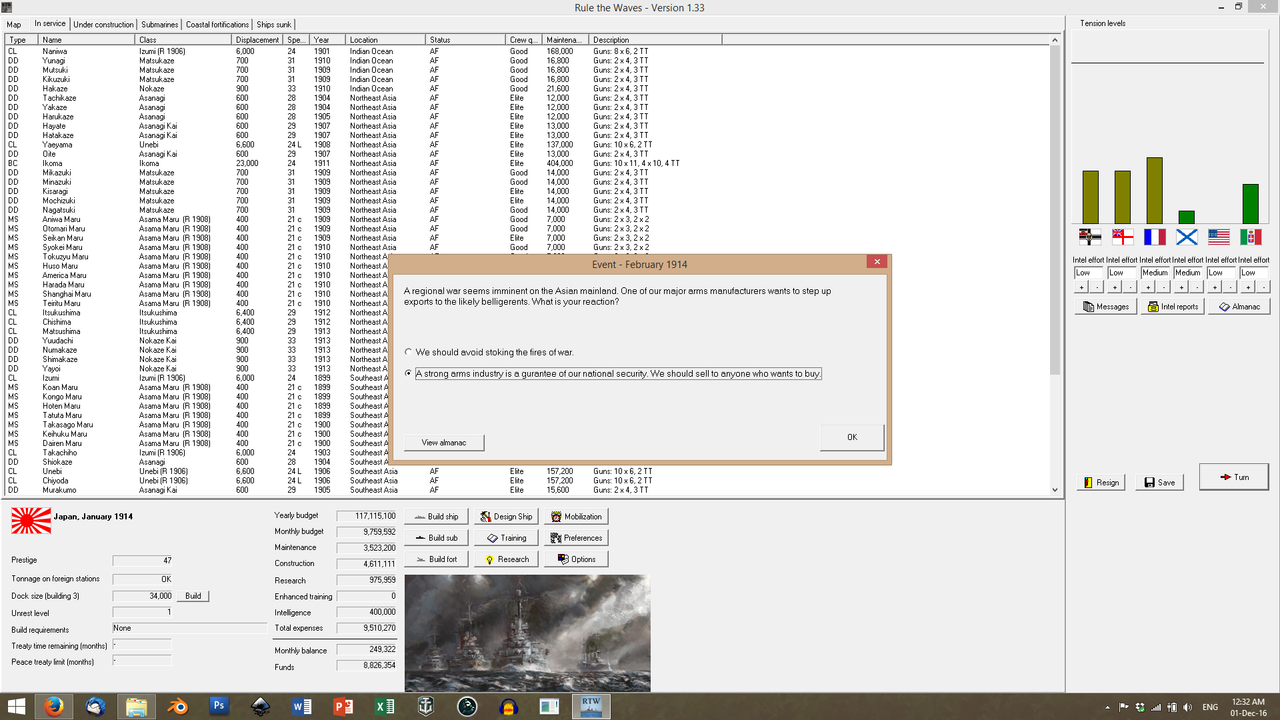

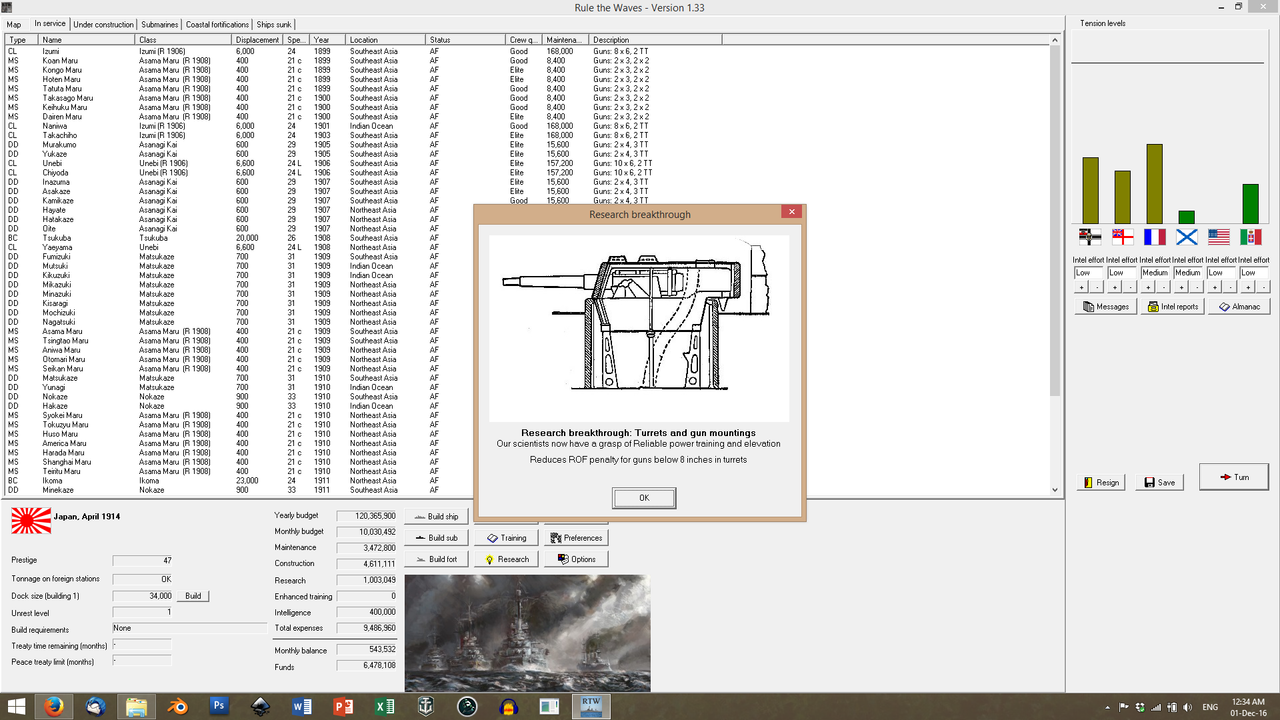

In March, the R & D department presented further improvements on targeting systems to the Admiralty and there was much rejoicing.

And they also presented an improved 9'' gun prototype. Unfortunately, the gun was too small for use in a battlecruiser and to big for use in a light cruiser. The Admiralty had nothing to use it on. So there was less rejoicing.

March also marked the completion of the new docks. Japan could now build warships of up to 37,000 tons.

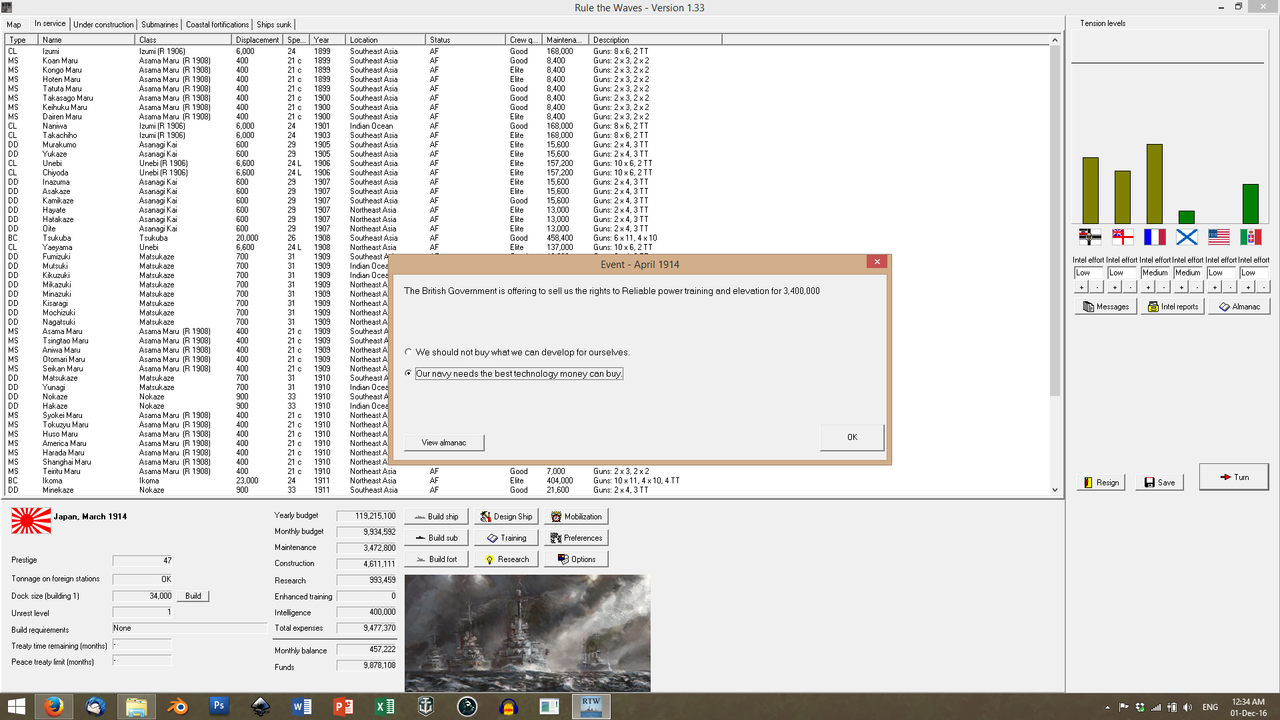

And in April, Great Britain approached the Admiralty with a 'thank you' note for their help in the China crisis and with a proposal for the Japanese who, maybe, would like to purchase the latest British designs on turret miniaturisation for a bargain price?

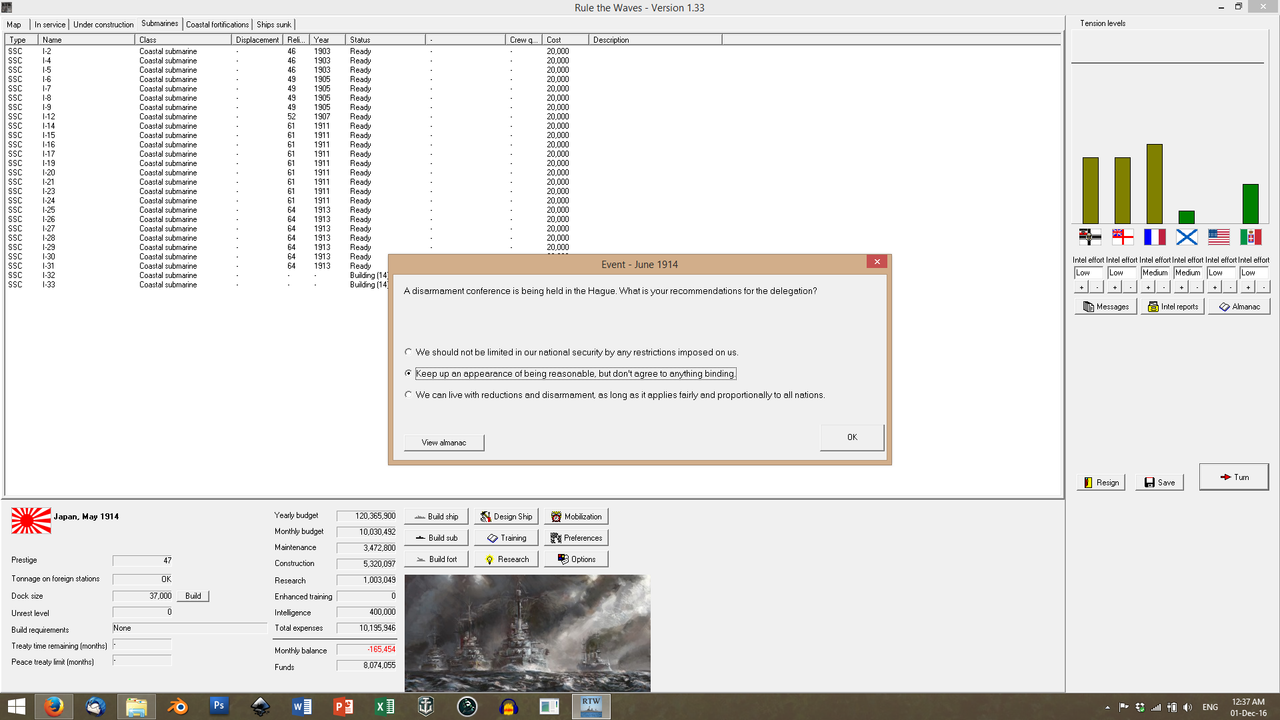

And then, in June, the international Hague Convention was held - a "step towards true peace", it was called. The Japanese were quite suspicious. This had Germany written all over it - any limitations on ship or weapon designs would allow the Kaiser's Navy time and opportunities to catch up. So, it was a very angry and very,

very determined Foreign Minister Katō who assembled his delegation and departed Kyoto, on the 2nd of June 1914.

Poll

Poll