In the Hague Convention, the support of the USA was crucial. Both the Japanese and the Americans were eager to further expand their navies and their spheres of influence, in contrast to the European powers, who were all too keen to maintain their relative lead and (in the case of Germany) limit their opponents' development while waiting for the opportunity to catch up.

However, with Japan and USA presenting a united front, the Convention came to naught in the disarmament front - although it did result in one of the first (and most well-known) codifications of the international laws of war.

In the upcoming years, Japan would

bitterly regret not taking a different stance.

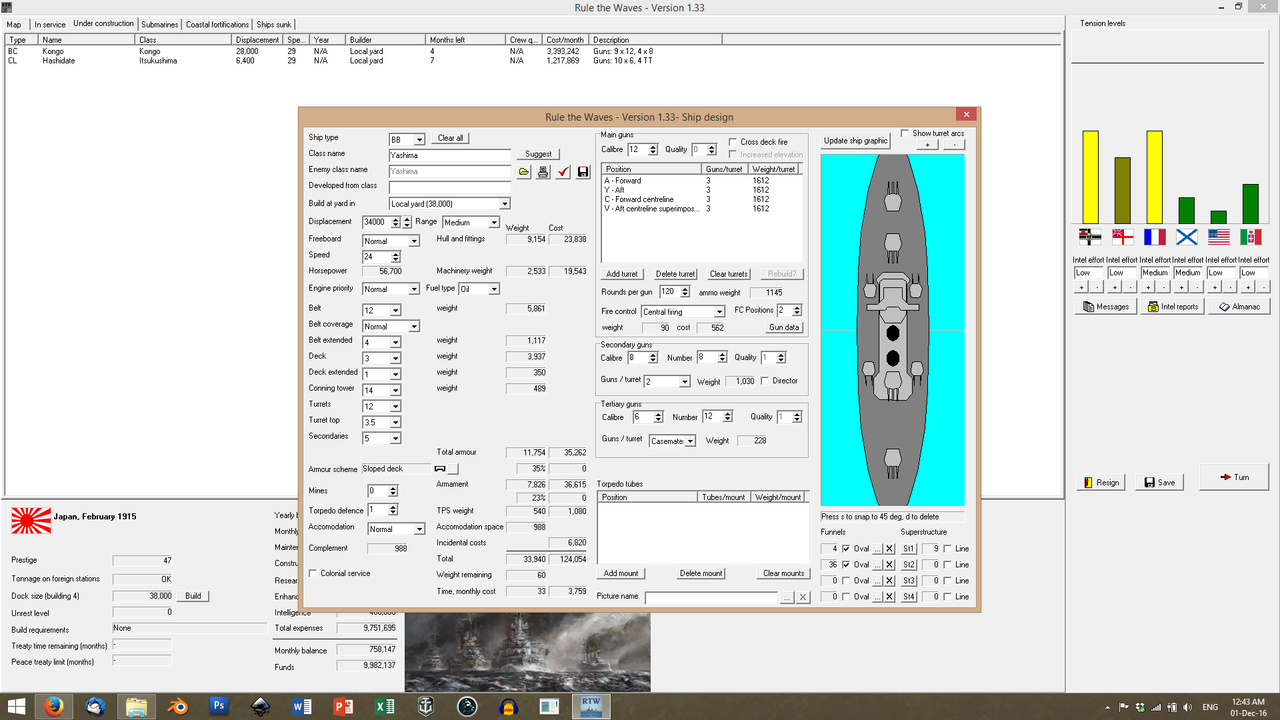

For now, however, the Japanese, satisfied by their success poured more money into their infrastructure. They could not yet afford the mighty Dreadnought they were envisioning; so be it. They would make sure that, when the time came, their ship would be the best and biggest of its kind in the world.

In August, with

Kongou less than nine months from completion, the R & D people reported new advances in torpedo propulsion. The Japanese torpedoes now could reliably reach 9,000 yards - a spectacular range.

Meanwhile, the new trade routes opened thanks to the inclusion of Tanganyika in the Alliance contributed significantly to the development of Japanese industry. The first rubber shipments arrived in August; the Sumitomo

keiretsu proceeded to buy out the Japanese branch of Dunlop enterprises and quickly developed into Japan's prime rubber manufacturers.

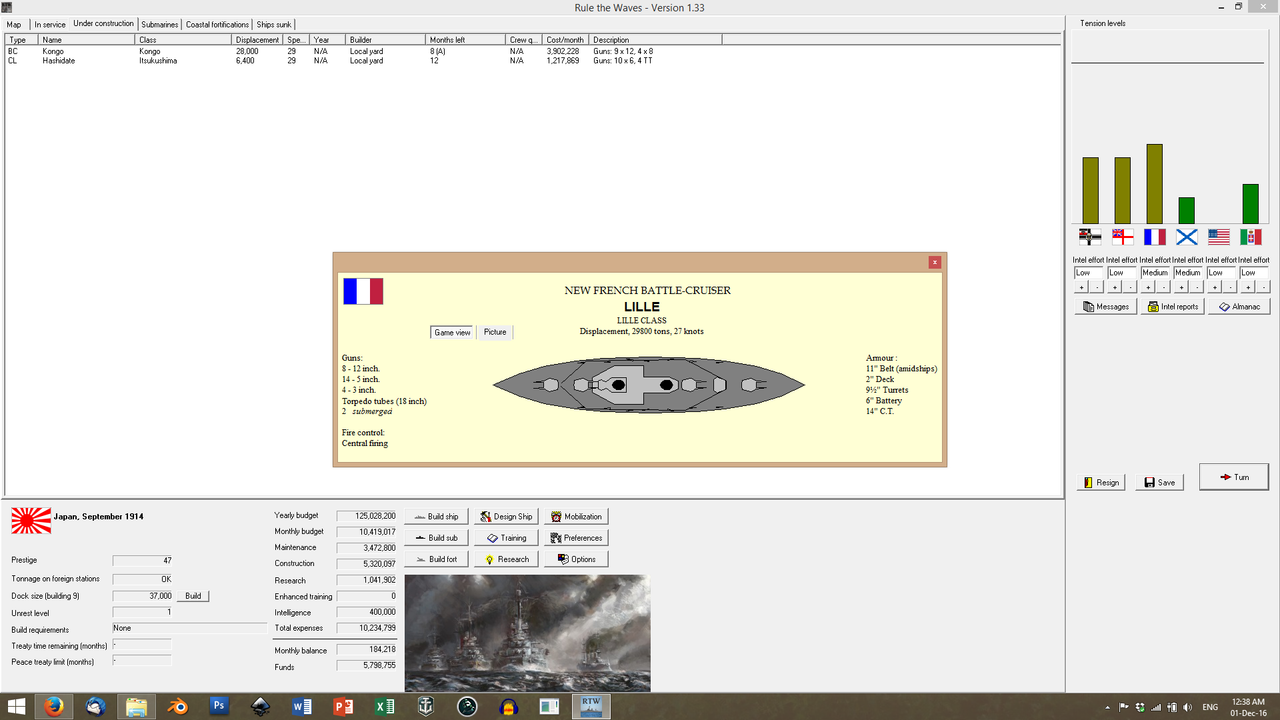

In a move that brought great joy and jubilation to the Admiralty, Military Intelligence surreptitiously acquired the blueprints to the new French battlecruiser,

Lille. The ship was notable for its heavy armour but, in all other matters, it was inferior to

Kongou - its speed in particular. The fact that

Kongou was oil-fired meant that she could maintain her speed consistently and dictate the terms of the engagement.

In October, Sumitomo Enterprises funded further expansion of the Yokosuka dockyards, in order to manufacture their new cargo haulers. The Admiralty was quietly jubilant, despite the money being 'poured away' towards colonial developments.

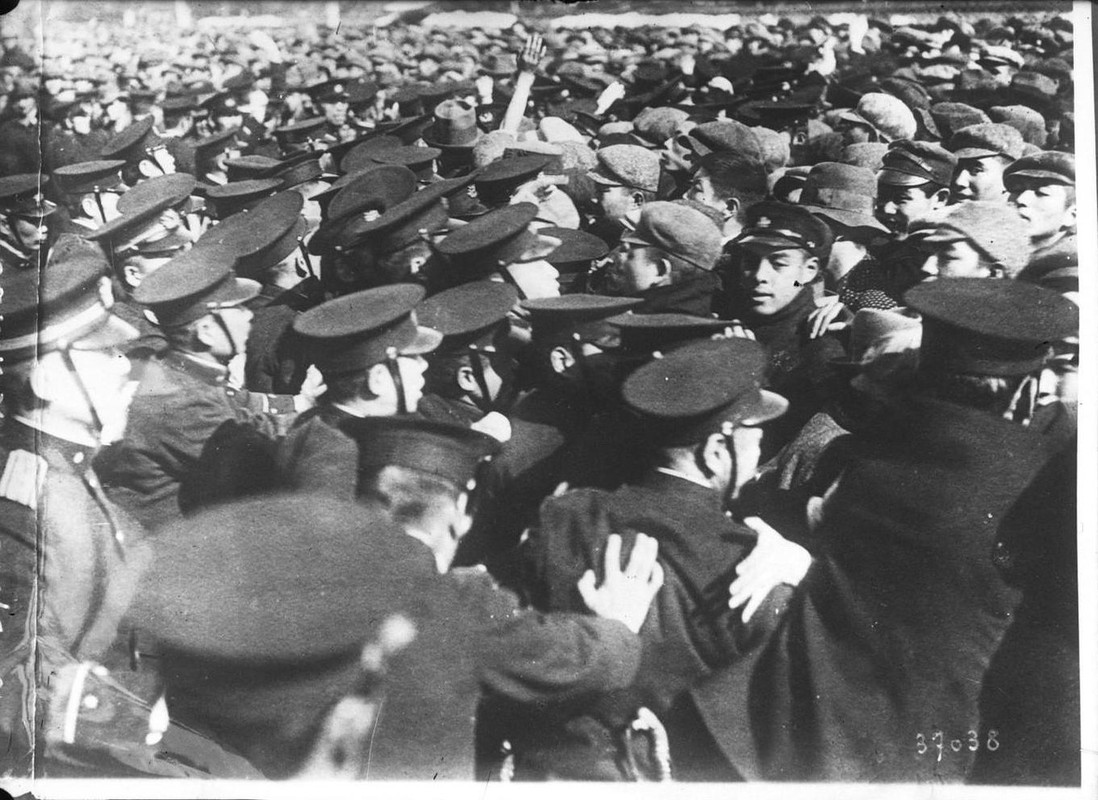

The crew of Tsukuba voting in Formosa

The crew of Tsukuba voting in Formosa

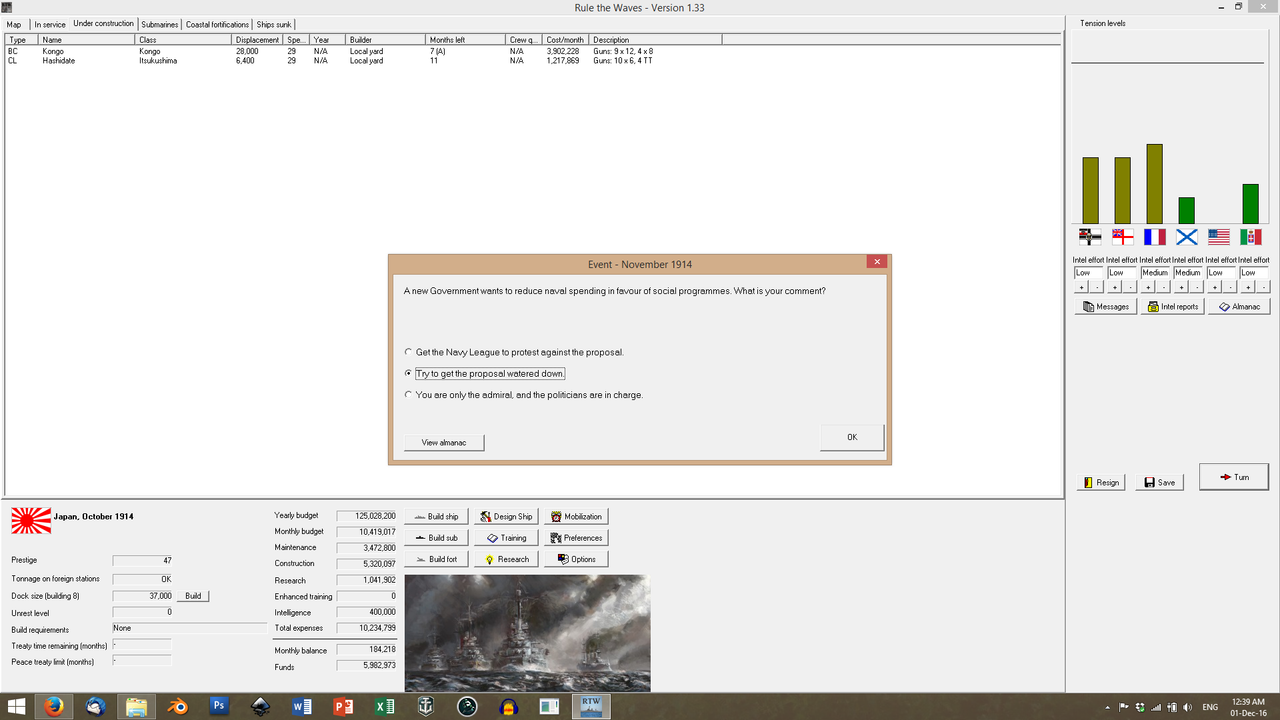

This changed after the late October elections. Ōkuma Shigenobu came to power as the new Prime Minister: he was a reformer, a firm believer in the necessity to establish a constitution, a patron of the sciences and a supporter of the Japanese industrialists. Considerable funds were diverted from the Navy to the development of the Allied infrastructure; and societal reforms were implemented. The Navy grumbled and protested, but to little avail.

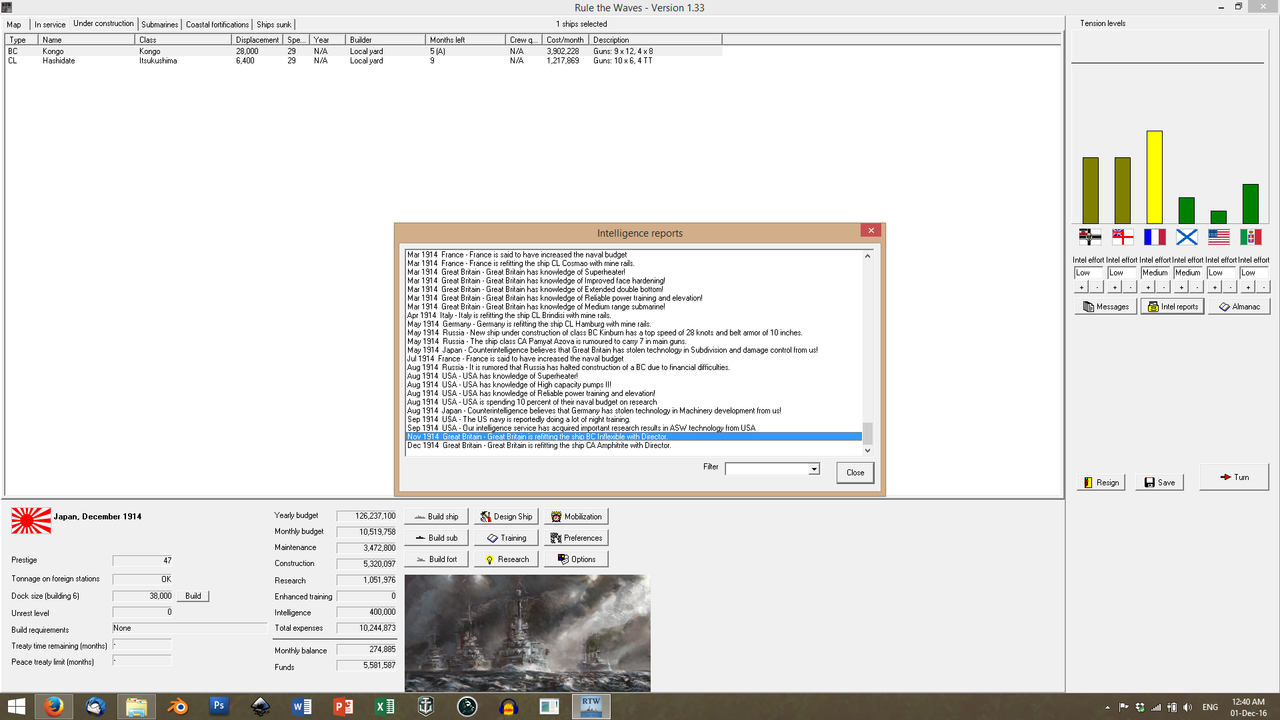

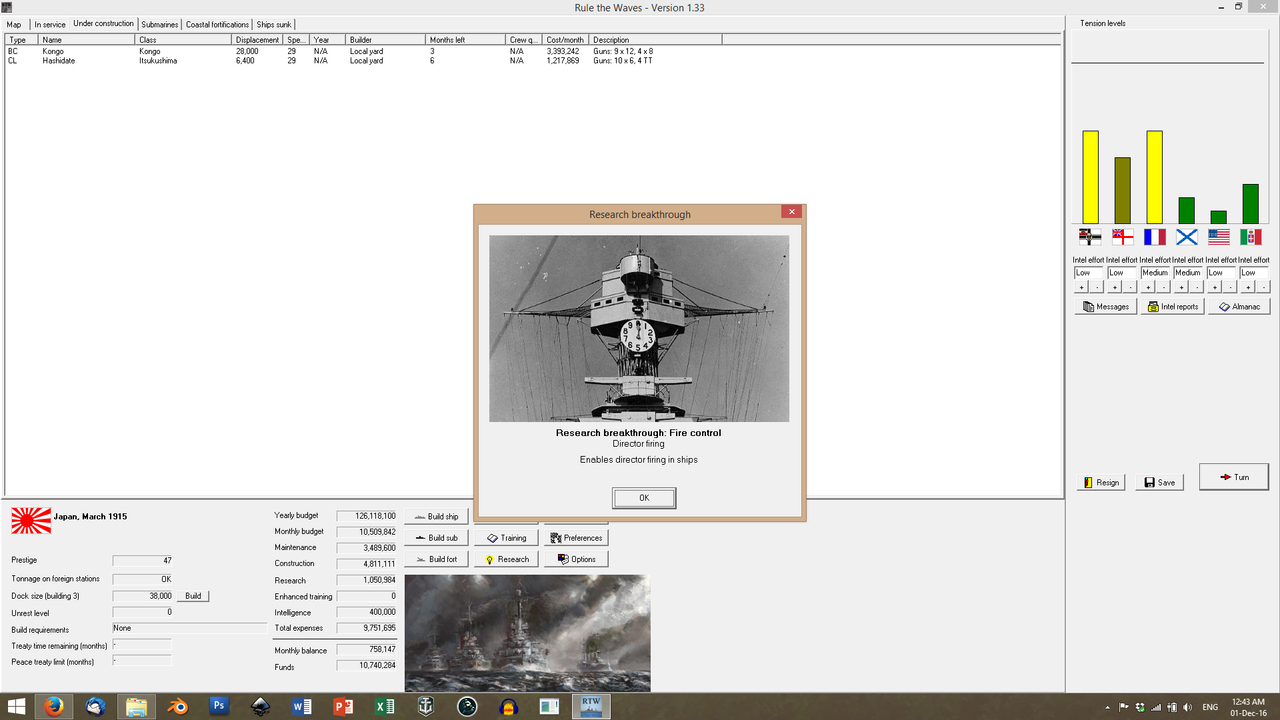

By December, concerning news had reached the Japanese Admiralty. Their one advantage over their European adversaries - the well-vaunted Japanese accuracy - was now in danger of being surpassed. The British were outfitting their ships with 'Fire Directors'; a new, revolutionary targeting system that would render Japanese technology obsolete. This was disheartening, to say the least. Japan had always depended on qualitative superiority over her enemies and now that advantage was being denied to her.

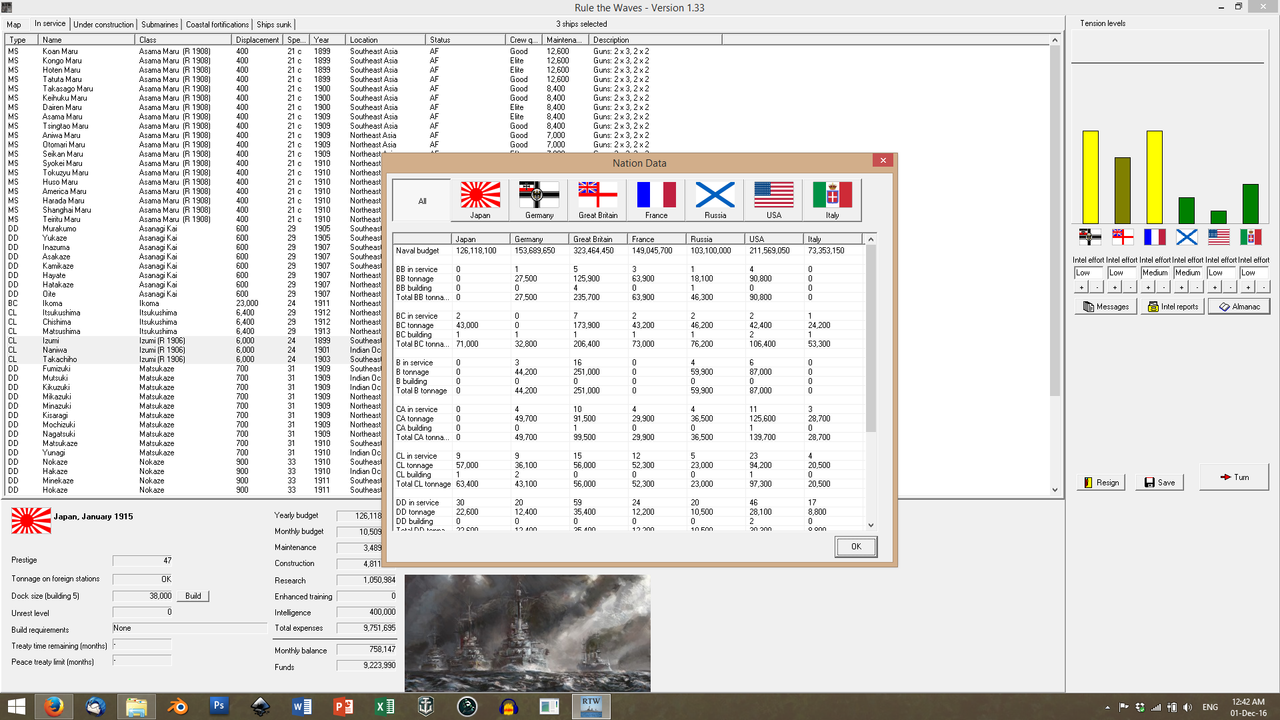

Small wonder. Ōkuma's reforms, while greatly benefiting Japanese society had gutted the Naval budget. Japan was spending less on her Fleet than Germany; who, by the way, had launched her new Dreadnought and had laid down a new battlecruiser.

Once again, naval designers brought forward the designs for a Japanese dreadnought that would literally and figuratively blow the competition out of the water. Once again, the response came from the Admiralty: "We can't afford it."

But in March, finally! Good news. R & D had caught up with the Brits. Japanese directors had made their appearance later than their British counterparts, but were every bit as good as them, if not better, given the Japanese technological lead in optics.

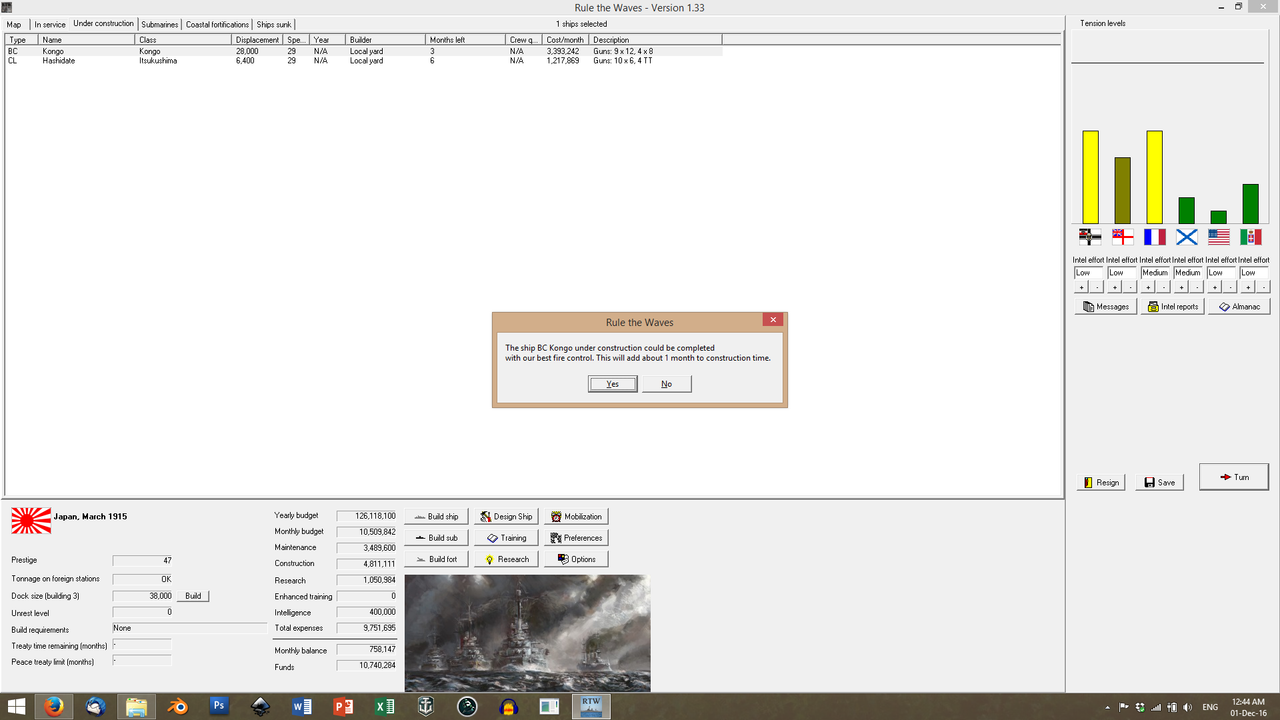

Even better, they could be seamlessly integrated in the construction of

Kongou, for only an extra month of work. Other, older ships would require drydock time.

...which the Navy was more than willing to pay for.

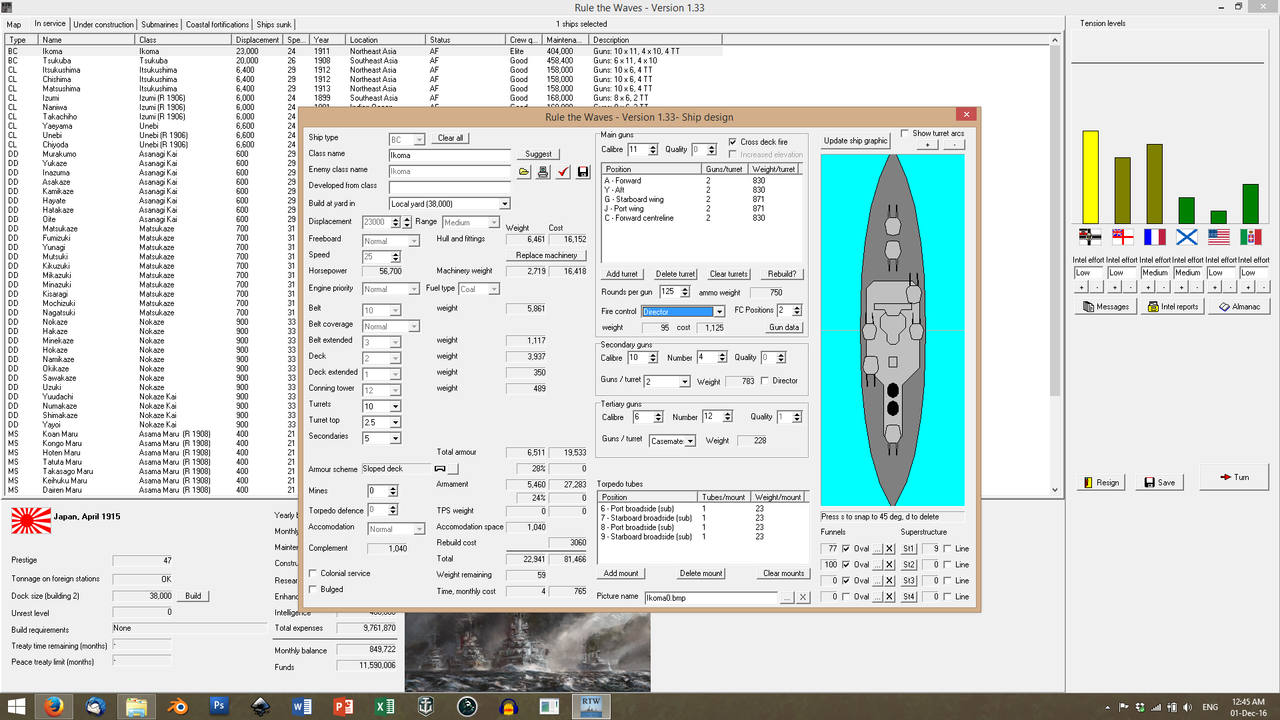

Ikoma received a fire-control upgrade, as did

Tsukuba. Unfortunately,

Ikoma's design allowed little room for outfitting her with improved engines or other modernisations. Changing her boilers to oil-fired designs would give her an extra knot of speed, but she was so compactly designed that the process of stripping out the old machinery and fitting in the new engines would cost as much as a brand new capital ship. In contrast,

Tsukuba's much less cluttered design allowed for a

massive rebuild, that raised her speed to 29 knots and completely overhauled her firing control. The 'elder sister' could now keep up with

Kongou even if her guns were growing to be on the anemic side.

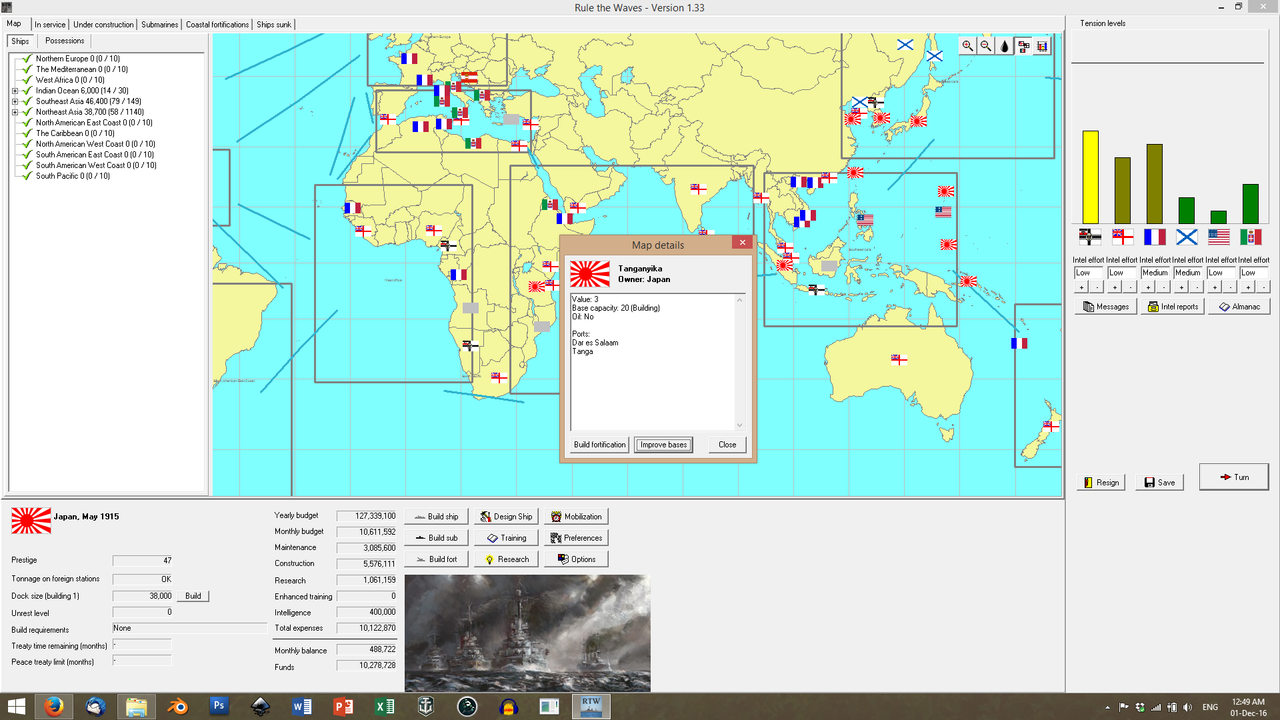

And in May, more funds were poured into Tanganyika. The German-begun railroad was completed by Japanese engineers and a local workforce; new rice farms were started in the Serengeti area; the rubber industry was expanded; the harbour was further expanded, schools were re-established and the training of local administrators was continued.

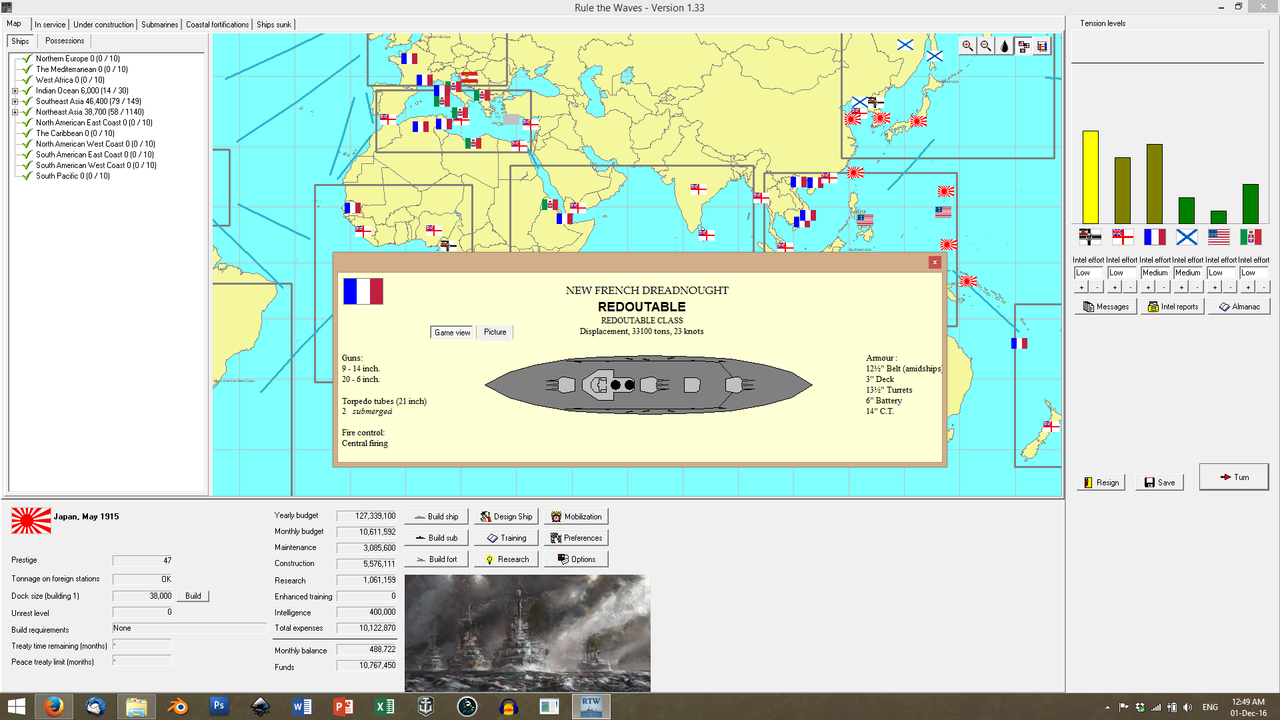

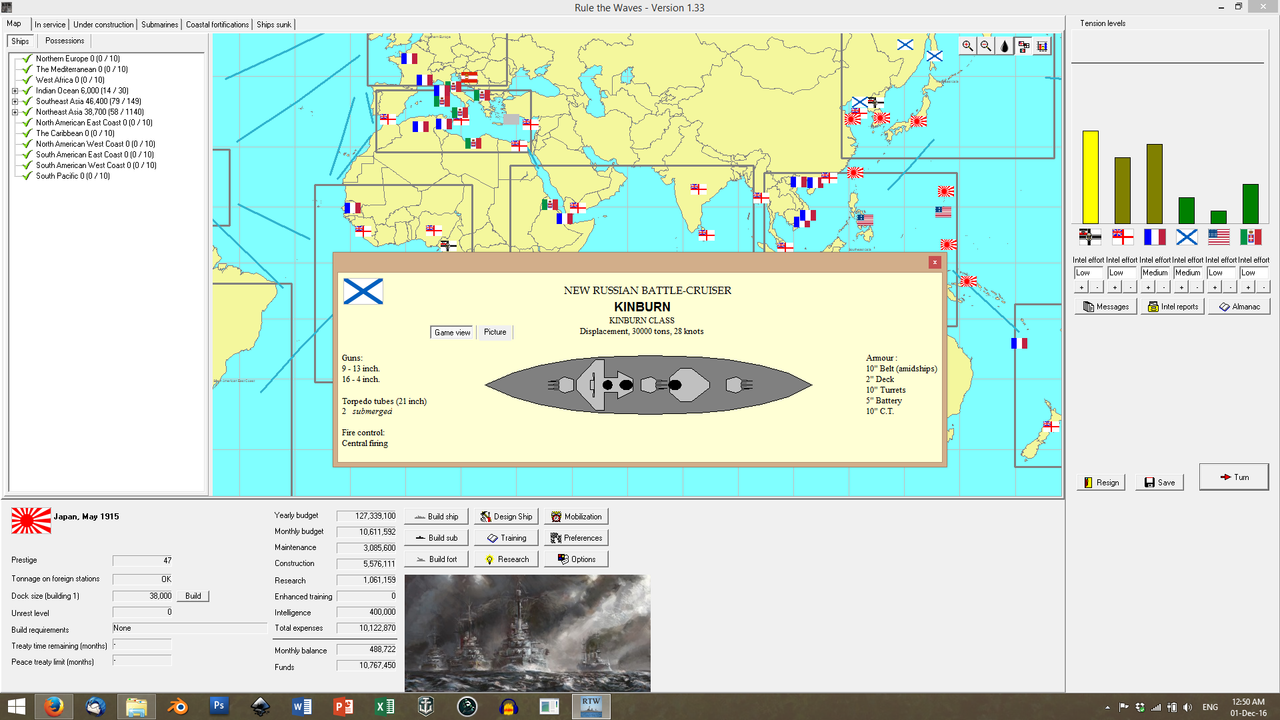

However, despite the general social improvements, it was a cold awakening for the Admiralty when Intelligence reported in with their new acquisitions: the blueprints for the new French dreadnought and Russian battlecruiser.

It was a very sobering thing to acknowledge that, even with their inferior firing control, these ships would outgun anything in the Japanese navy. The

Russians were catching up, for the sake of all the Kami! There was a rather bitter undercurrent in the relations between the Admiralty and the Government at the time...

...which was only partially addressed by the commissioning of

HIJMS Kongou.

Wait.

What?

Poll

Poll