- PART 5 -

Making Enemies

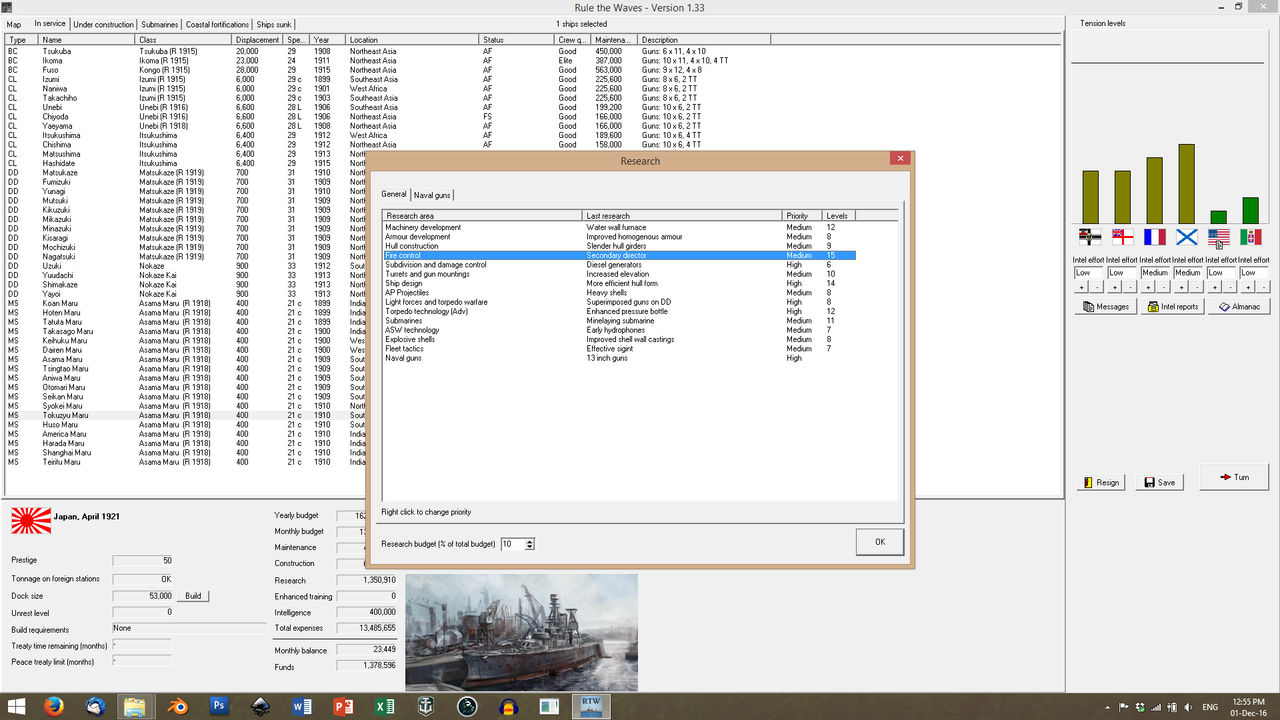

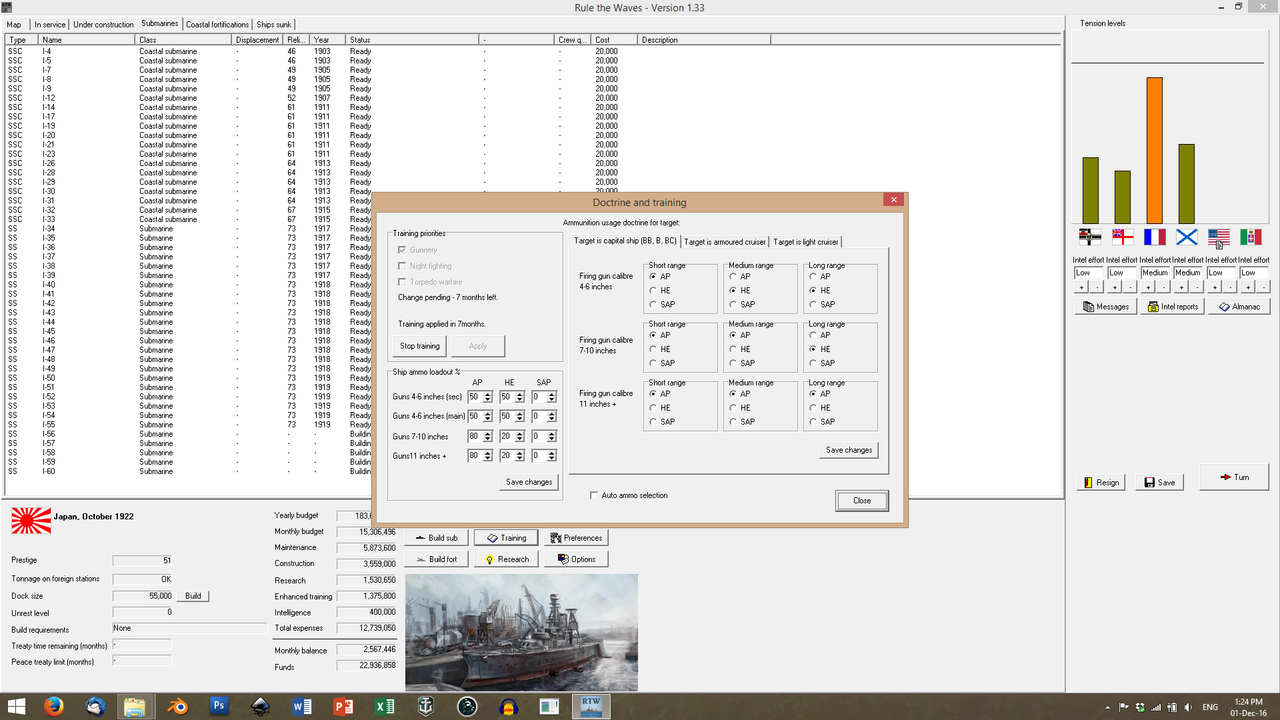

In April, the R & D department proposed a simple yet amazingly innovative design: a secondary director, meant to provide central fire control to a capital ship's small-caliber batteries. It would need to be retrofitted to ships and would require time in drydock, but it would also make designs based on heavy secondary batteries viable - and would greatly boost the effectiveness of the already-mounted secondary guns.

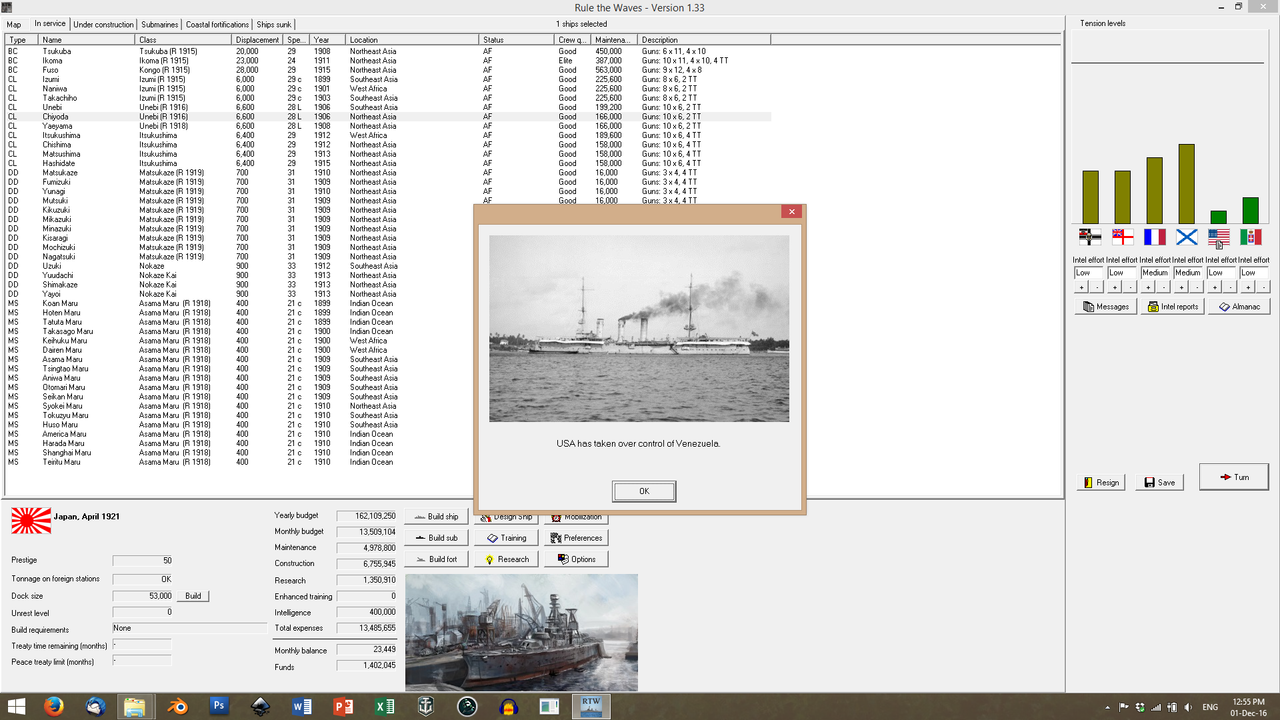

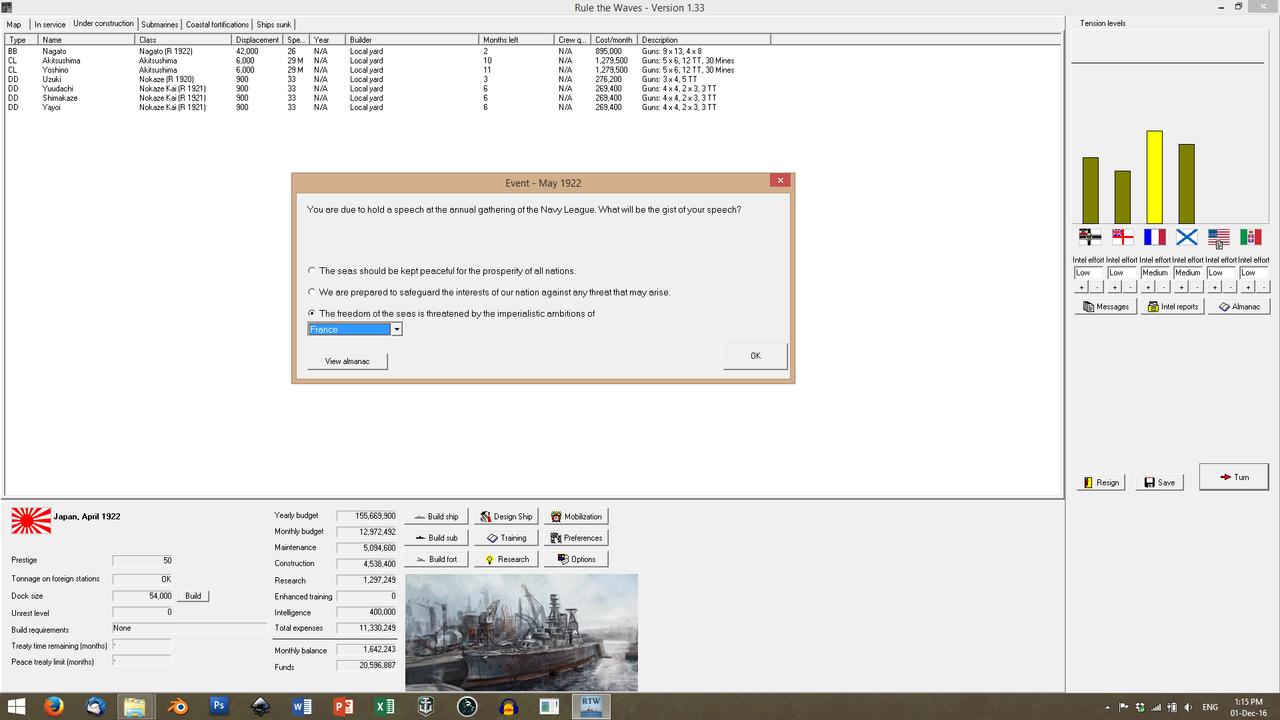

During the same month, a USA expedition occupied Venezuela. The Japanese Government had no objections to their ally extending their sphere of influence.

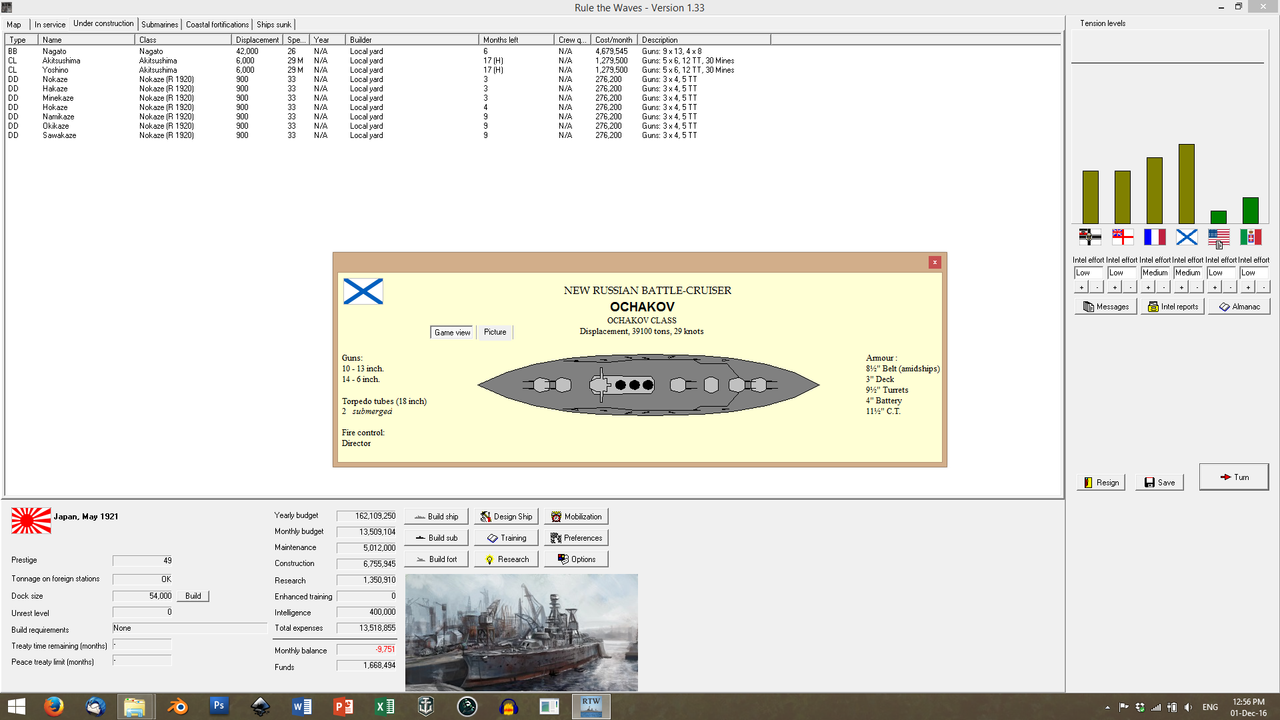

But in May - bad news. The Russians were building a Battlecruiser that was only 3k tons lighter than

Nagato, with a massive, 10-gun broadside. And more significantly - a fire control director.

Ochakov would take them years to complete, but she would, apparently, outperform

Fuso in all but her armor when she left the slipways. It was up to the Japanese to have an answer until then.

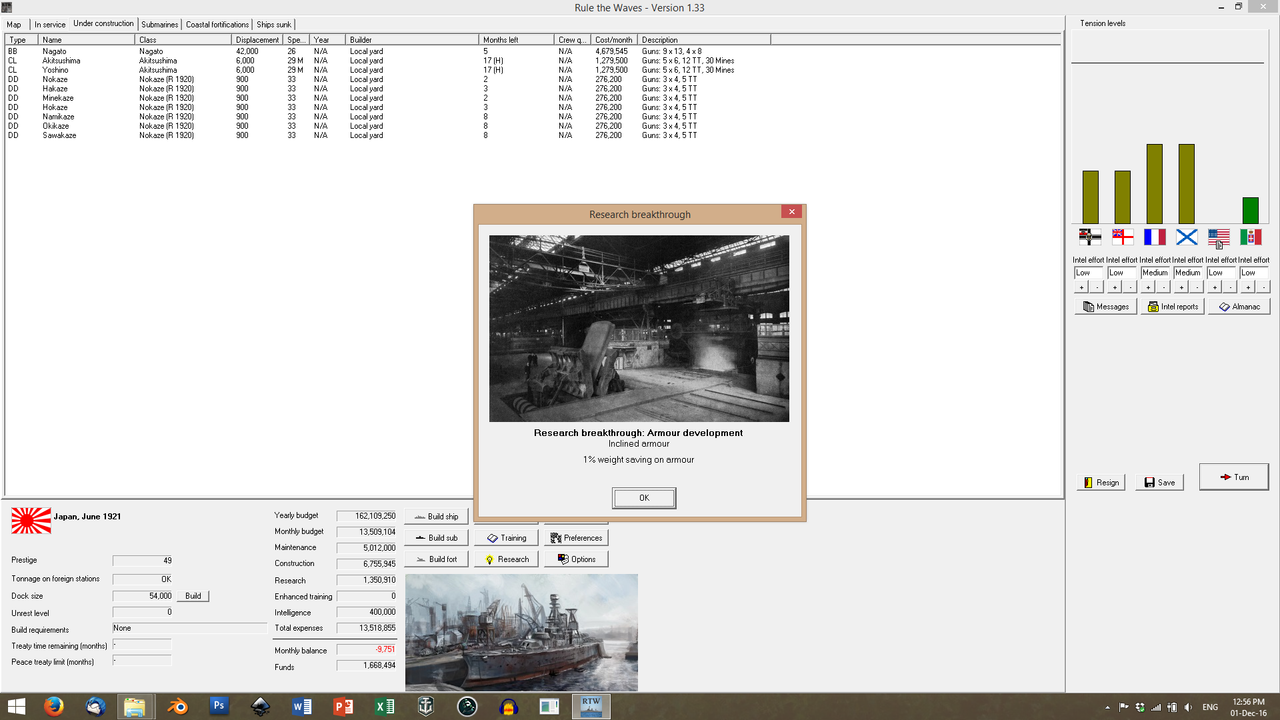

The work of the R & D department in torpedo defense carried over, to some extent, to armour schemes. Experiments with sloped layers of armor yielded promising results.

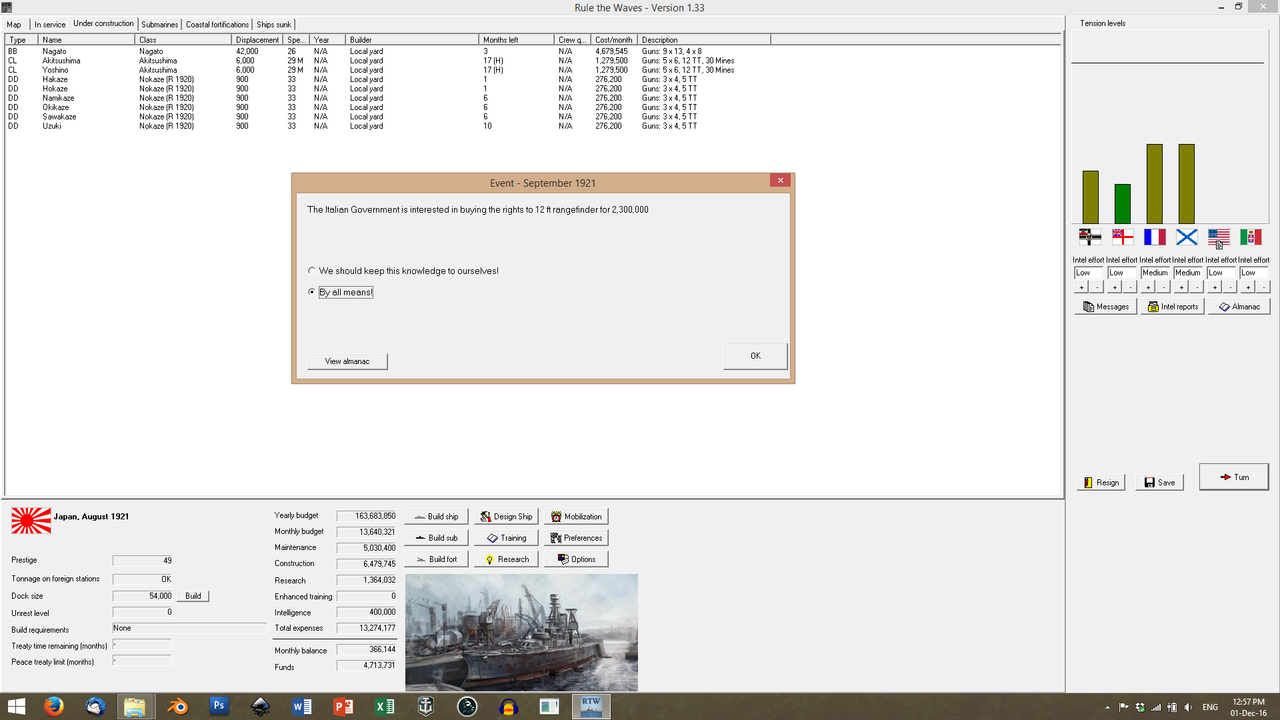

In August, the Italians approached the Japanese with a proposal to acquire the licence for the large rangefinders used in

Fuso. The Admiralty had no objection - Italy was no threat, tensions with them were low and it was better for them to

pay for the information than for them to acquire it clandestinely anyway. The Japanese had long since accepted that if the Italians wanted to acquire some confidential piece of technology, there was little one could do to keep them out.

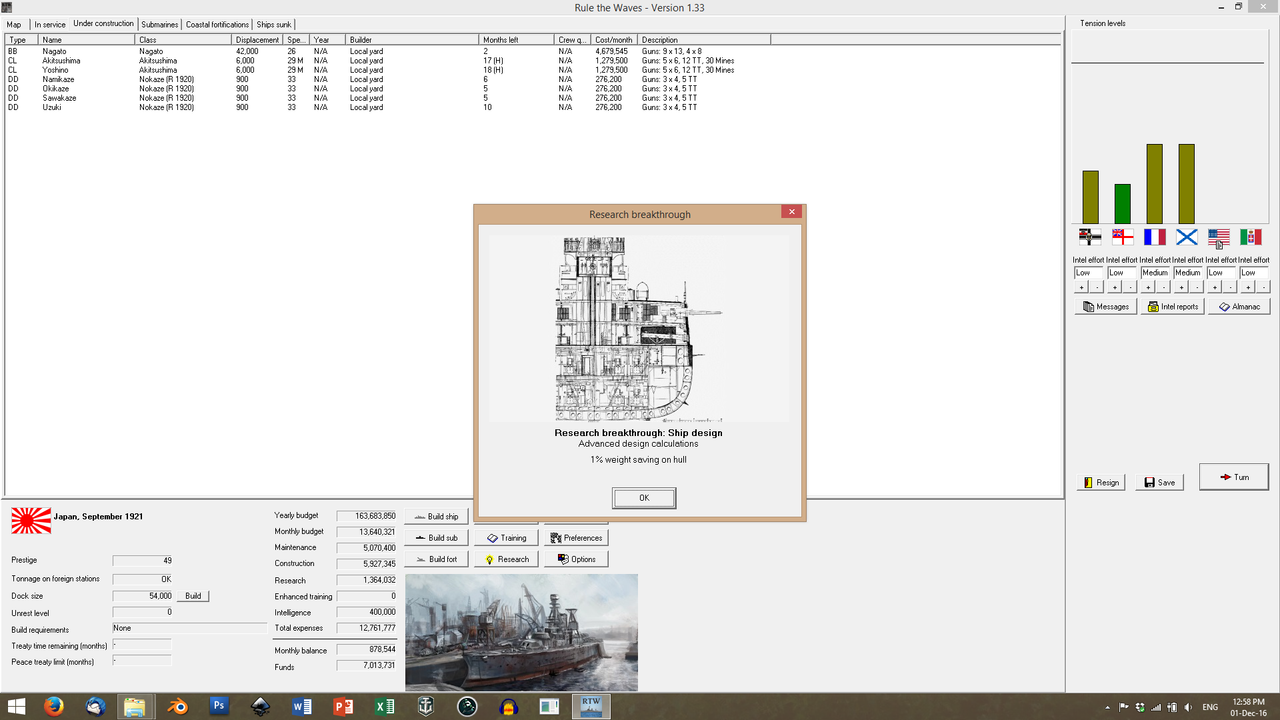

In September, the R & D engineers managed to overcome yet another hurdle in the implementation of their designs. Japanese hulls would now be more hydrodynamic and subjected to less stresses than before.

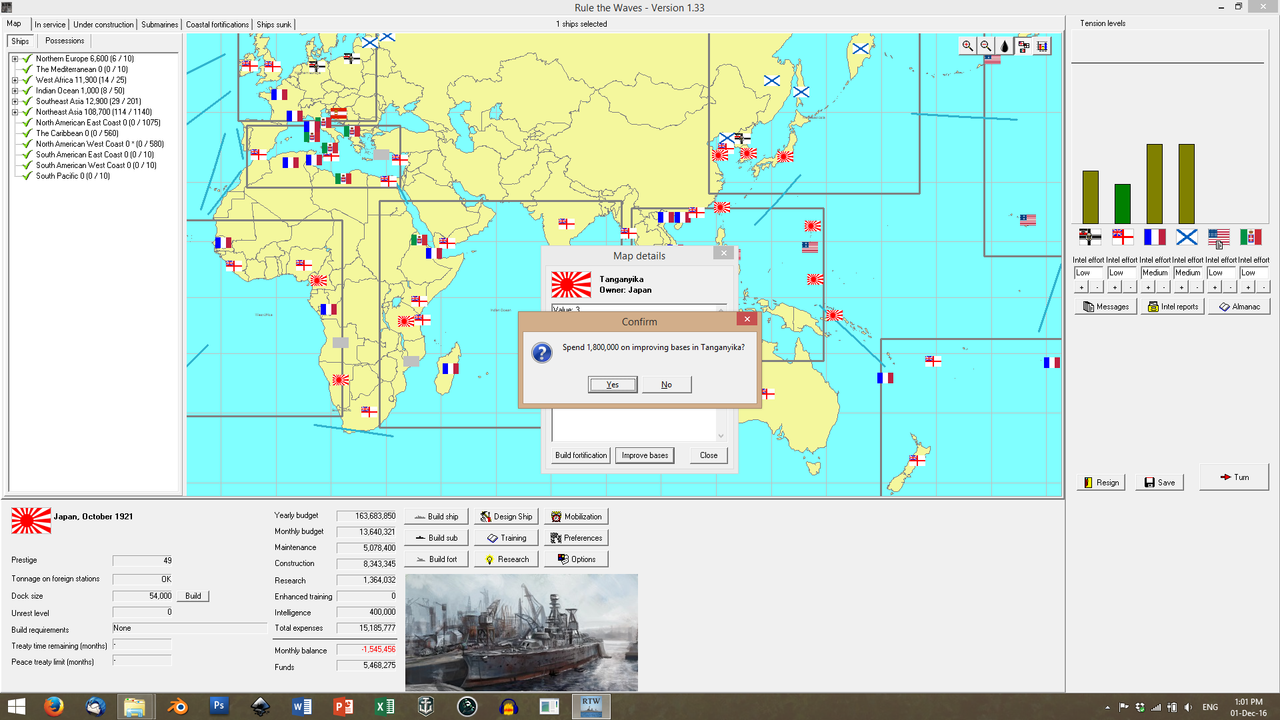

During the final years of the Hara administration, another program for further improving Japan's African holdings was implemented. With tensions with France rising, the Navy was not averse to improving their military port and supply depots in Tanganyika, as a counterweight to Madagascar.

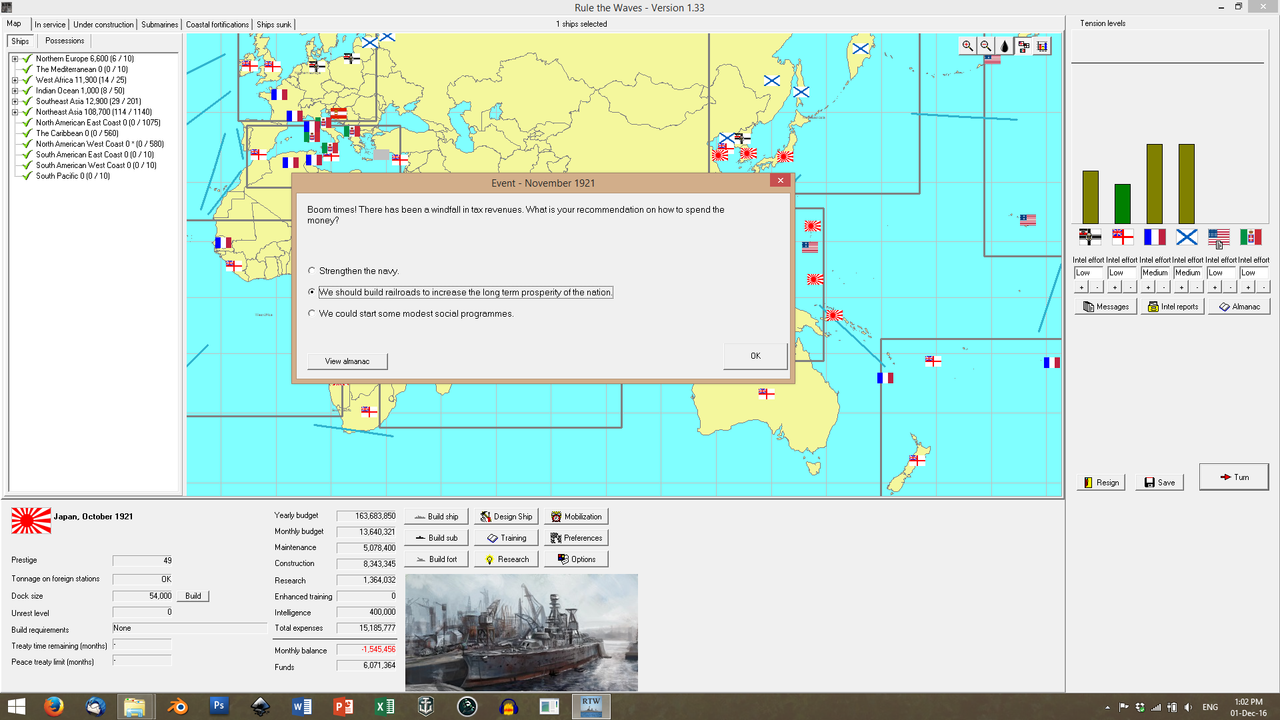

Meanwhile, the final stretch of the Trans-African Railway (アフリカ鉄道を通じて - "

Afurika Tetsudō o Tsūjite") was laid down, with a planned completion date of May 1922. When that was done, it would be possible to transport goods, troops and supplies overland from Tang to Kamerun and Namimbia in less than 48 hours.

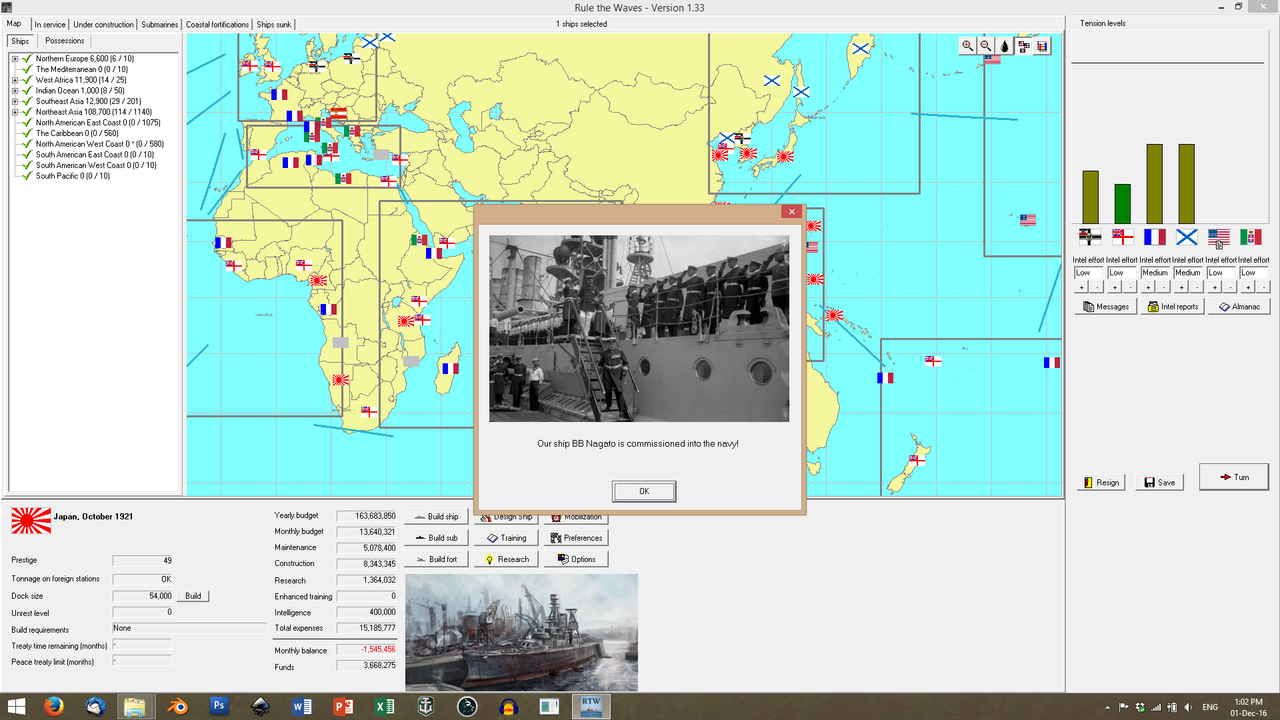

And, in October, the Navy rejoiced:

Finally

Finally after so many years, Japan joined the Dreadnought club.

The commissioning was a grand affair. The Emperor attended, but his declining health made it impossible for him to officiate; his son, Hirohito, led the ceremony as Prince Regent. Naval attaches from several countries were present as the world's largest capital ship was formally accepted into the ranks of the Japanese Navy. The hopes of an entire nation rested on her.

...And then she

immediately re-entered drydocks, to have her guns adjusted for increased elevation and the newest fire control systems integrated. Thankfully, the costs of

that were minimal.

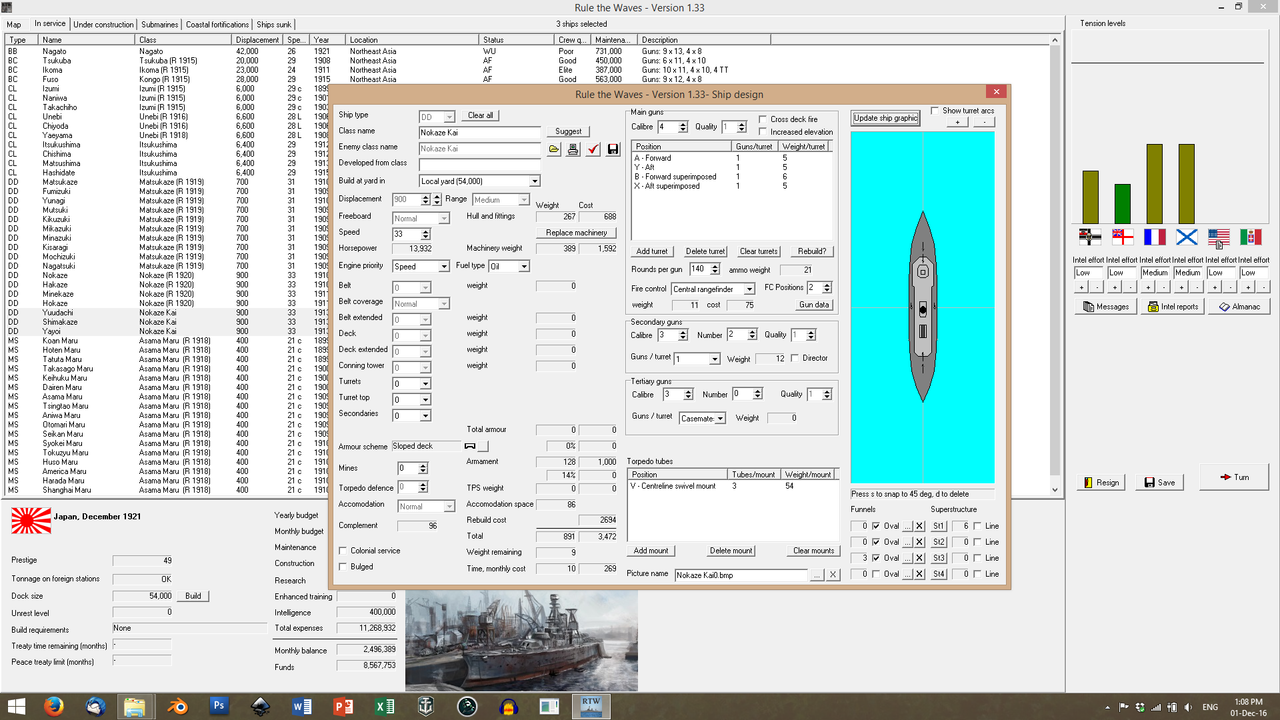

The Navy assigned the freed-up funds to the re-building of the

Nokaze and

Nokaze-Kai destroyers. The ships were given new boilers; and the Nokaze-Kais were stripped of some of their torpedo mounts in exchange for a centrally-mounted triple launcher, four 4'' guns and a small secondary battery of 3'' popguns. They were turned into true gunships.

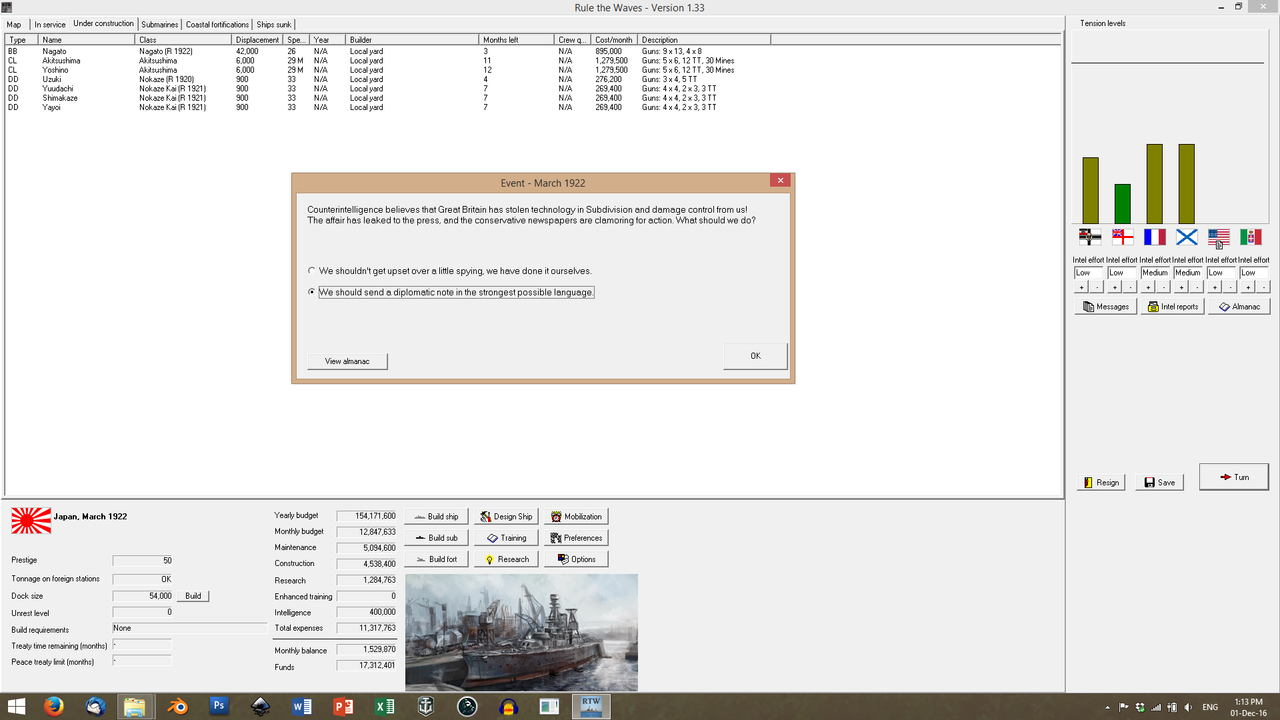

In March, Counter-Intelligence traced down a theft of older Torpedo Protection System designs by Grand Britain operatives. Old Albion had been foiled in her attempts to procure the designs by legal means and had resorted to theft. The Japanese bristled like hedgehogs. The 'Bond-Taiga crisis', named so after the two most active agents involved in the Intelligence operations from both sides only served to raise tensions - Albion had gotten what she'd wanted.

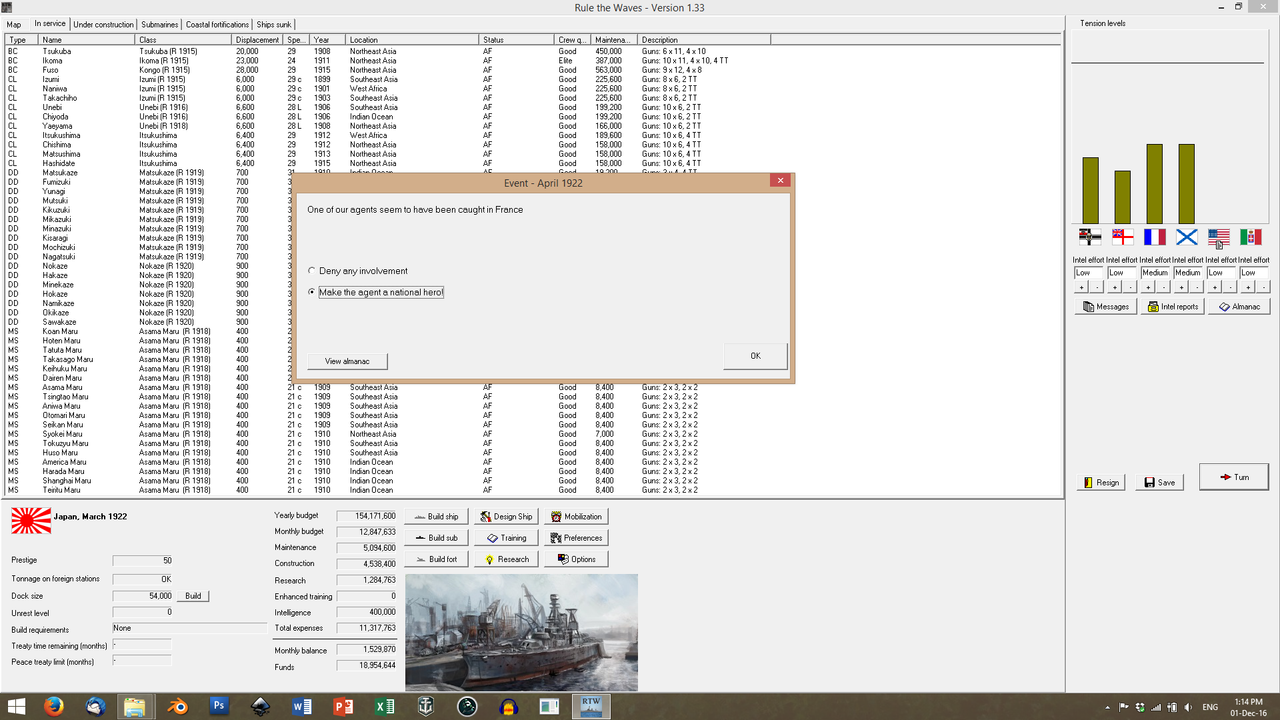

Japan was not so lucky. A Japanese mole, Francois Dumas, was identified and captured by French Intelligence; he would spend the next three years in a high-security French jail. Japanese newspapers made a hero of him, which only served to further aggravate the French.

In May 1922, elections were held in Japan; for the first time, every male citizen of the Alliance over 21 was given the vote, including all natives in African and Pacific holdings. Representatives were elected from all provinces.

The new Prime Minister was, once again, Yamamoto Goynbee; the new Government would be a Coalition Cabinet. Hara had given a good accounting of himself in integrating the new territories into the Alliance, but was considered to be too conciliatory in his Foreign Policies and his weakening of the Navy was a sore point, even among the citizens of the new holdings. Under Goynbee's administration Hara would receive the prestigious post of Minister of African Matters (アフリカ問題担当大臣 -

"Afurika mondai tantō daijin"), a position for which he was eminently suitable for and for which he would, actually, be more remembered than for his stint as Prime Minister. "Hara's Years" would be a golden boom time for Japan's African holdings and Hara would grow to be a close friend of Foreign Minister Kato, who was assigned to return to his earlier post. Interestingly, Kato had chosen to run as a Tanganyika representative and had received a stunning 76.5% of the votes.

Fresh out of the Dumas scandal, the new Government was called to take a position on the matter. After a brief interview with the Chiefs of the Army and the Navy, Goynbee and Kato drafted what would come to be known as the 'Formosa declaration' - a whithering

j'accuse of French policies in the Far East. Tensions, as expected, skyrocketed.

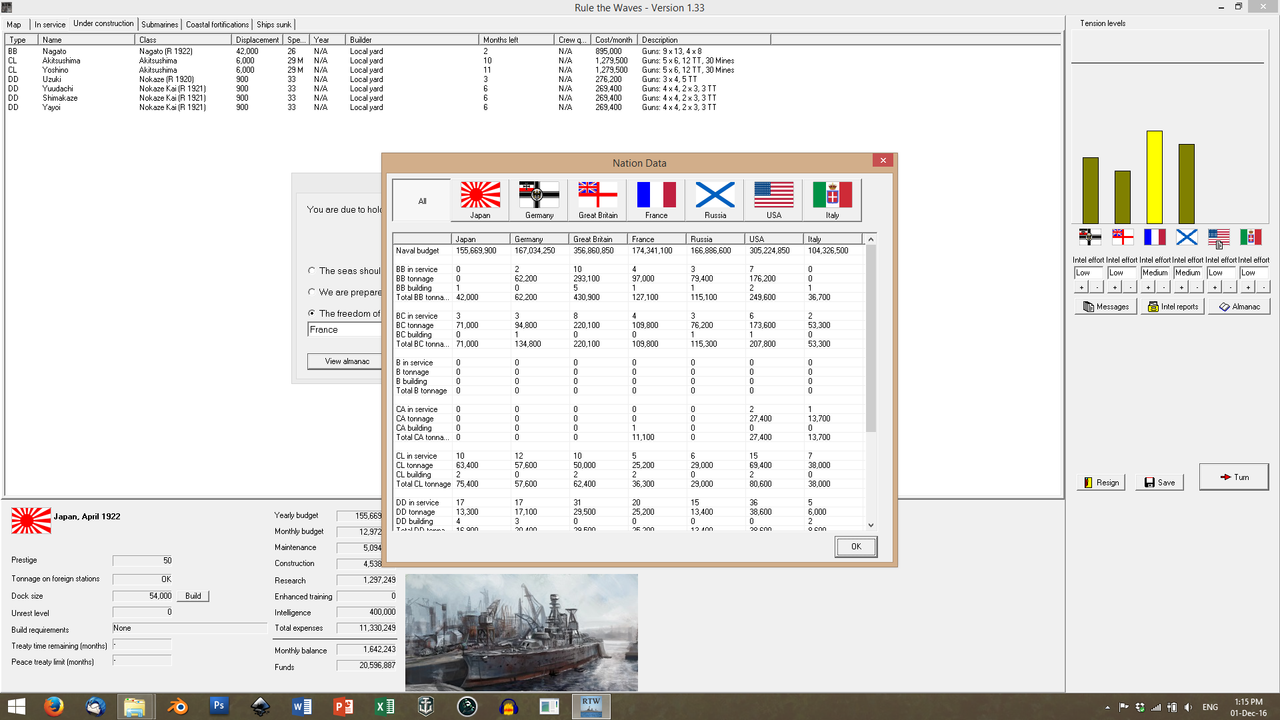

The French Navy was superior to the Japanese in every respect but three - but

these three points, the Japanese felt were

decisive:

Firstly, the French battle-line consisted of small dreadnoughts and battlecruisers. The Japanese Admiralty felt that, provided favourable engagements were pursued, the bigger and more powerful JApanese capital ships could carry the day.

Secondly, the Japanese would have the support of the Americans, which would, hopefully, pin a large part of the French fleet in the North Atlantic, thus allowing the Japanese to defeat them in detail.

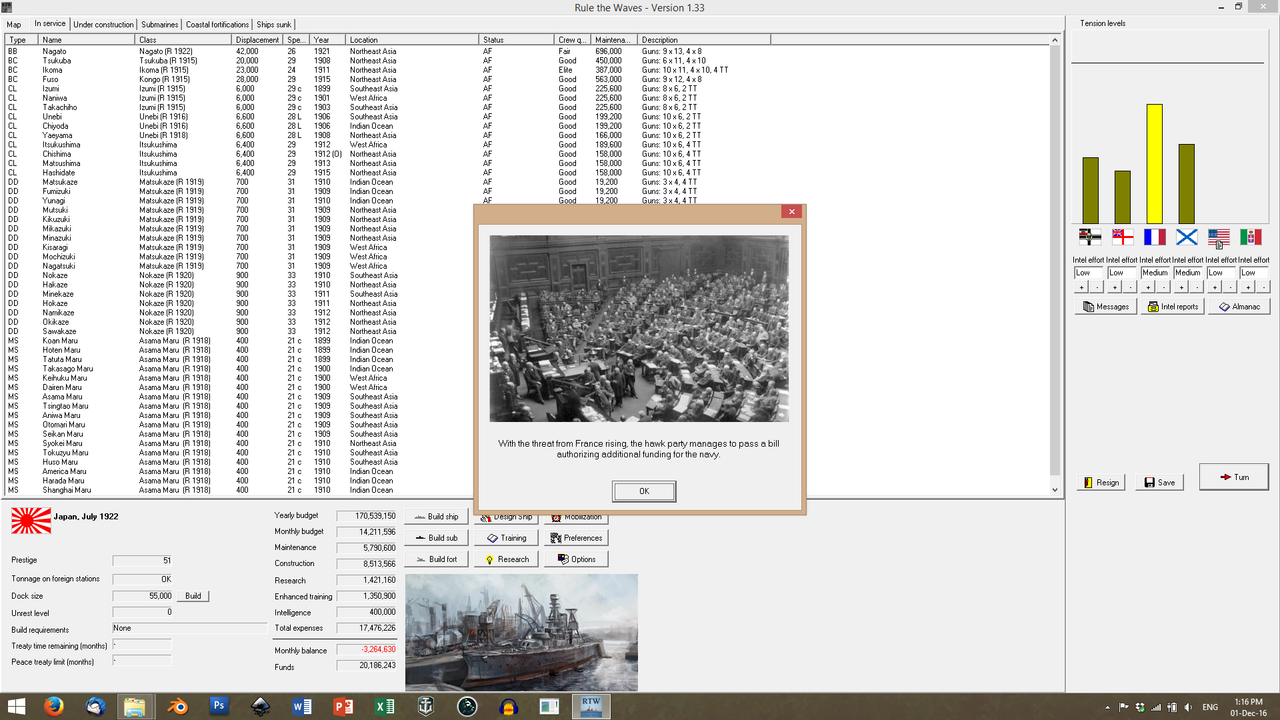

Thridly, for the first time in a while, the Admiralty had faith in the politicians running the show. Yamamoto was a strong supporter of the Navy and the Naval budget was sure to increase as tensions rose.

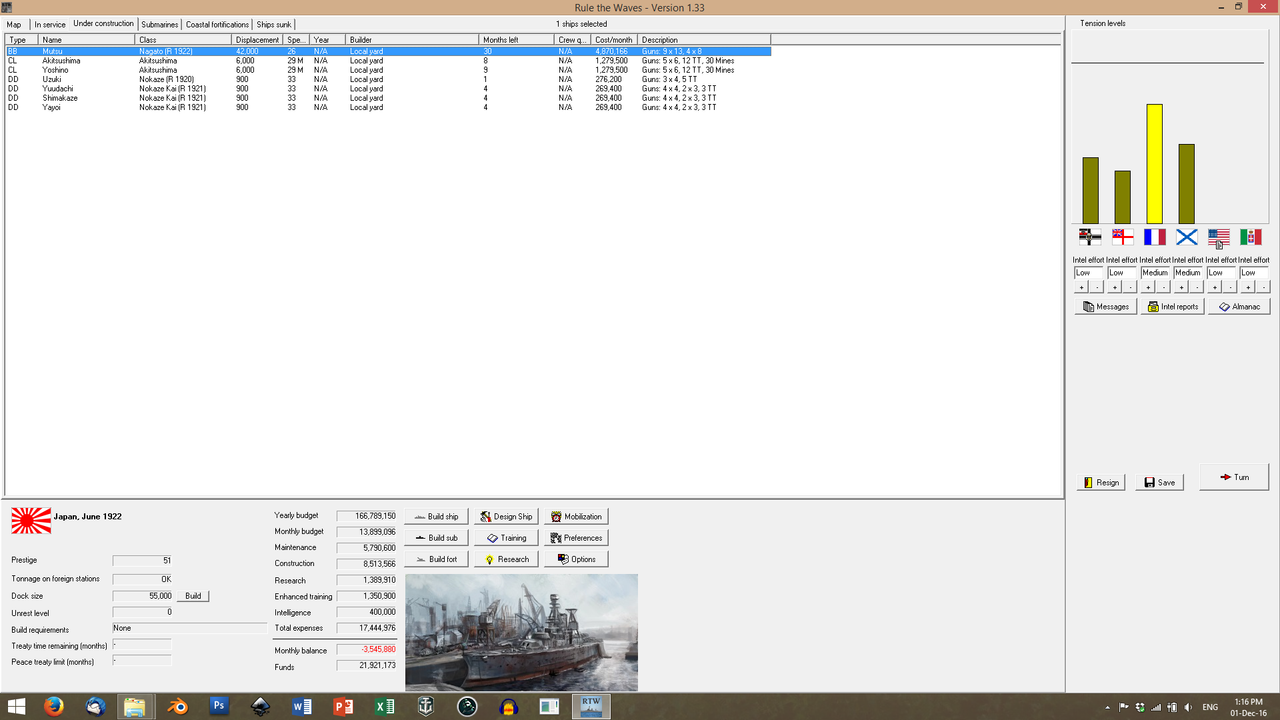

They were correct. Although it was impossible to

immediately up the Naval budget, Yamamoto channeled sufficient funds to the navy that it was thought possible to start work on a second

Nagato-class. The ill-fated

Mutsu was laid down in June, with an expected build time of two and a half years.

Alas for poor

Nagato, she would never have a sister.

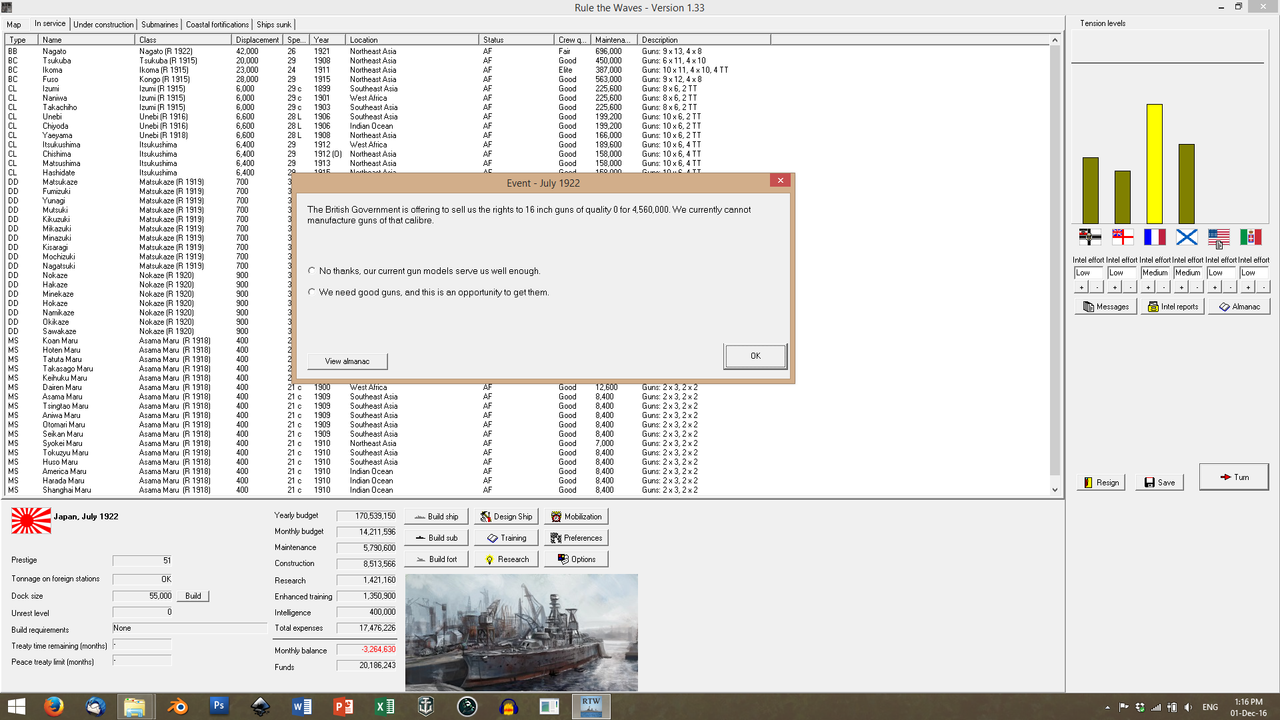

In July, the British Government, in a delayed but welcome attempt to defuse the 'Bond-Taiga' situation and in an attempt to get on the good side of what they predicted would be the winning party in a Franco-Japanese-American war, proposed to sell the Japanese the licence to the British BL 16 inch Mk I rifles. The Japanese were ecstatic at the chance to finally implement truly 'capital'-caliber guns in their ships and the deal went through without a hitch.

This, of course, made poor

Mutsu hopelessly obsolete, even before her keel was completed. The Admiralty did not hesitate: the order was given to scrap what little work had been done so far and await further instructions. Funds were stockpiled, in anticipation of the coming war.

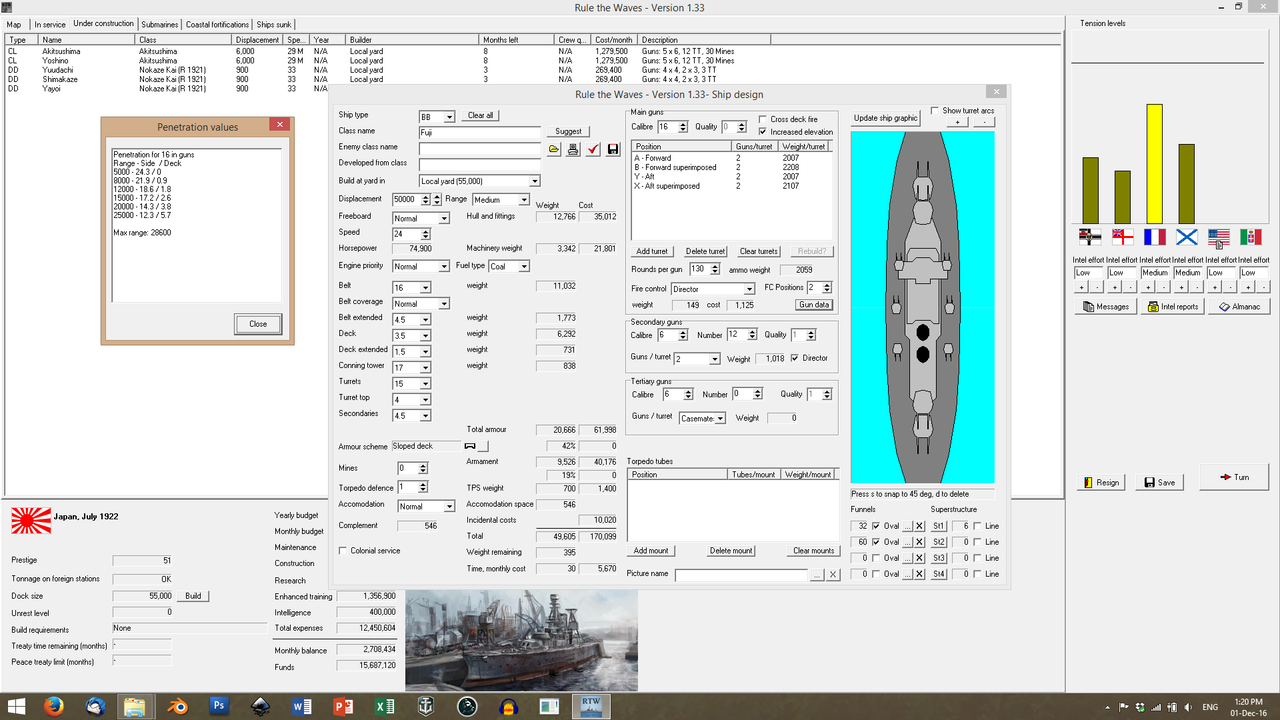

One of the proposed designs to take advantage of the new guns would be the

Fuji: an ABXY, 8-16'' dreadnought, implementing all new fire control systems and technical advancements. However, the Admiralty postponed the start of the construction, waiting,

waiting...

...for

this.

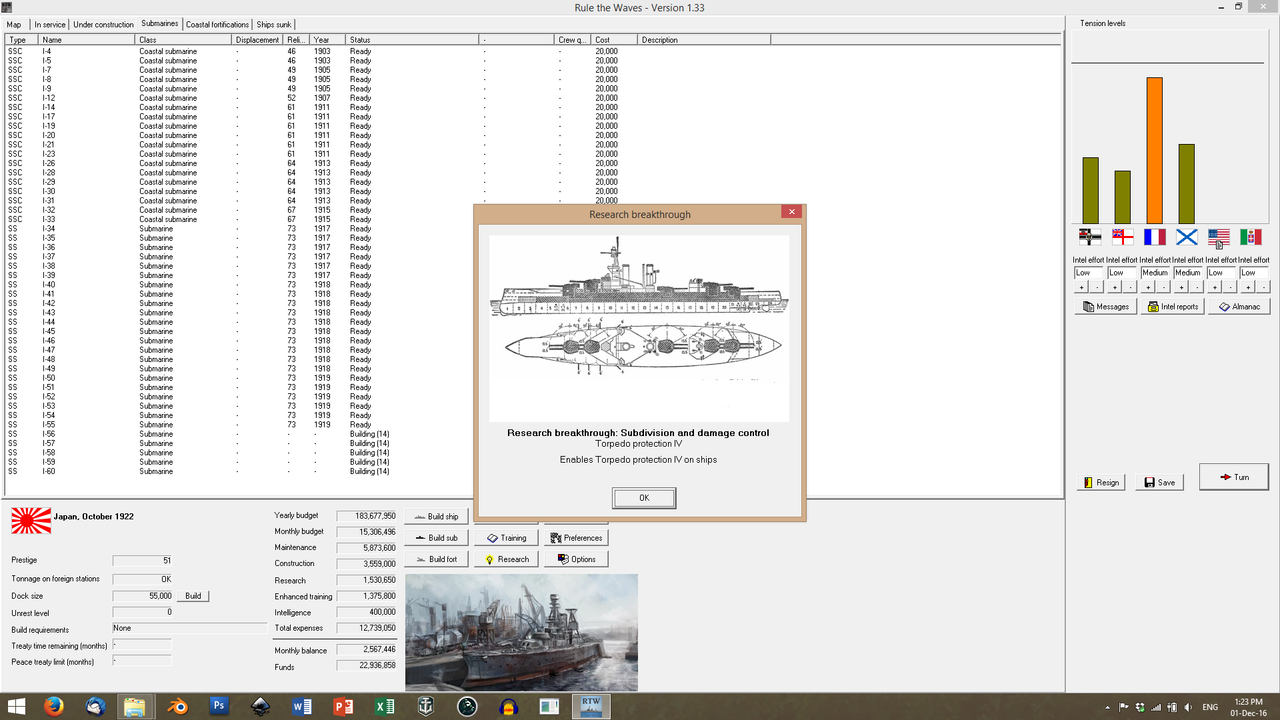

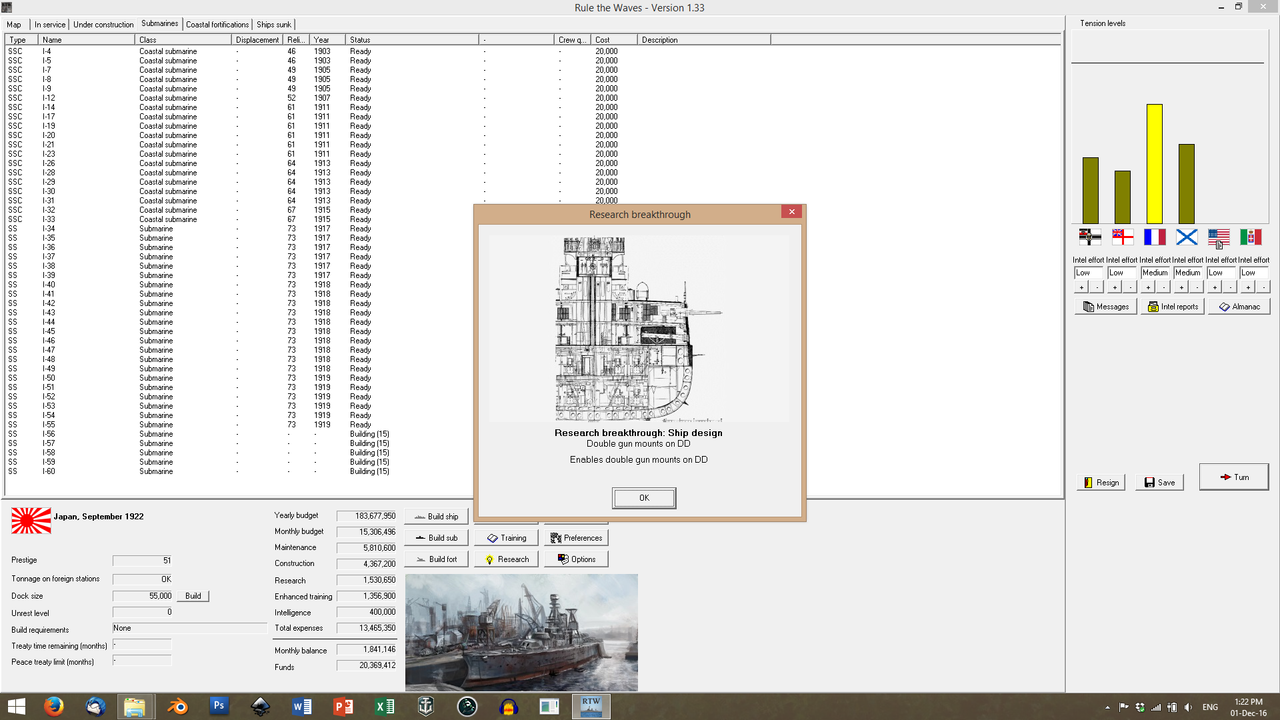

And, the R & D department being on a bloody

roll they also submitted a viable design for dual gun turrets on DDs, which made a lot of Japanese Admirals (especially the proponents of light torpedo warfare) very,

very happy indeed.

Things came to a head when France attempted to expand her holdings in the South China Sea, by attempting to occupy Borneo: an independent state in very friendly terms with the Japanese Alliance. The Japanese considered this a direct affront to the interests of their allies and their own; and a blatant disregard to their own custodianship of the Western Pacific. Once again, Kato jumped to action and showed his mettle.

The French forces arrived in Borneo only to be greeted by two Japanese task forces led by

Nagato and

Tsukuba; an American destroyer squadron based in Manila and operating under orders to assist their Japanese allies; and the British light cruisers

Fiji and

Sydney, with strict instructions to

"Guarantee and safeguard the interests of His Royal Majesty's allies in the South Pacific against any and all imperialistic action." The French squadron and troopships had no options but to withdraw.

With war being all but inevitable, the Japanese economy geared up into war footing. The African territories were reinforced with troops and the Army forces there were instructed to fortify and prepare for opportunistic and surprise attacks; guerilla forces were dispersed in inland outposts. The Navy started intensive live-fire training exercises. And R & D provided the Admiralty with improved torpedo mount designs and high-quality 5'' rifles, in anticipation of the modernisation of the Japanese destroyer forces.

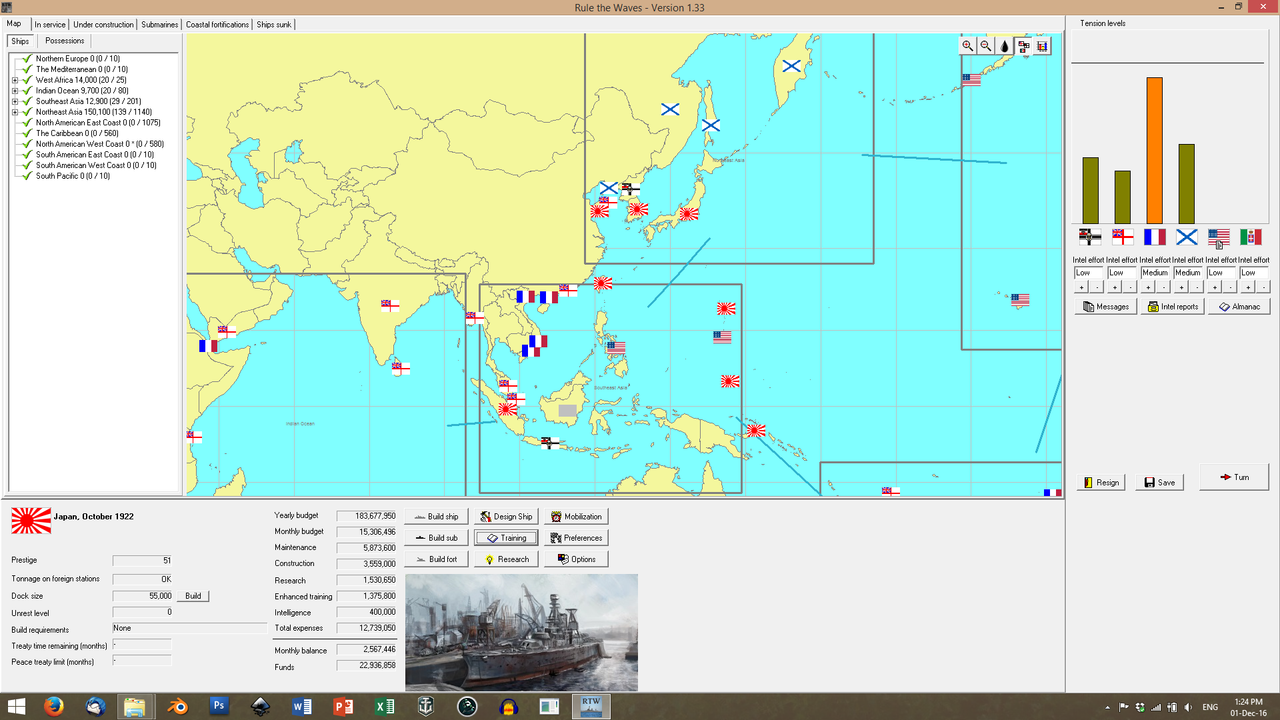

In October, this is what the Japanese saw as their future battlefield. A ring of Japanese bases surrounded a 'core' of heavily fortified French territory in Southern China. The plan called for joint operations with China and combined sea-borne and land attacks, supported by the Japanese fleet, to shake the French grip on their northernmost holdings. Since France possessed no holdings near the Japanese 'home islands', it was thought that they would be moderately safe from raiding and seaborne attacks - old

Tsukuba was deemed sufficient to handle interception duties, with all other capital ships detailed to supporting land operations.

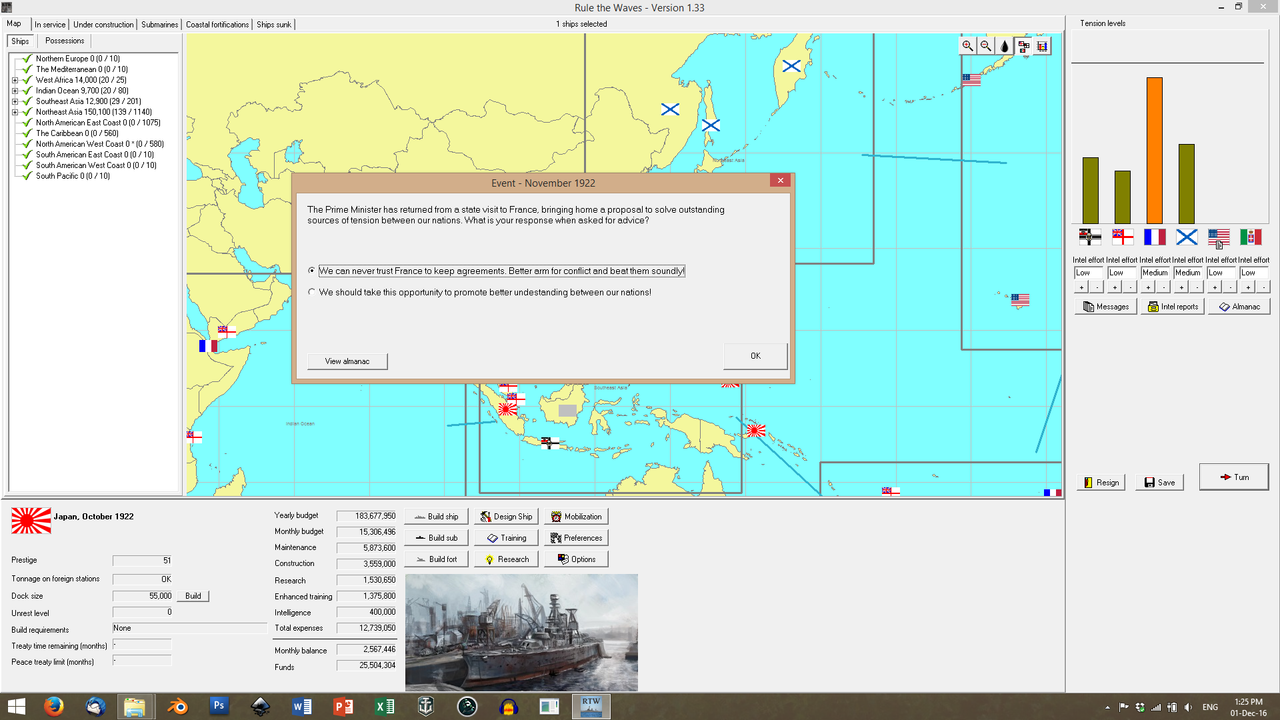

In the end of the month, Foreign Minister Kato and Prime Minister Yamamoto received a communique from French President Millerand, in a last-minute attempt to stop the war. Unfortunately, the mutual disarmament terms the French proposed were by no means acceptable to the Japanese; and, even if they had been, the Japanese had no intention to avoid war with a nation that they felt had grossly violated their sovereign sphere.

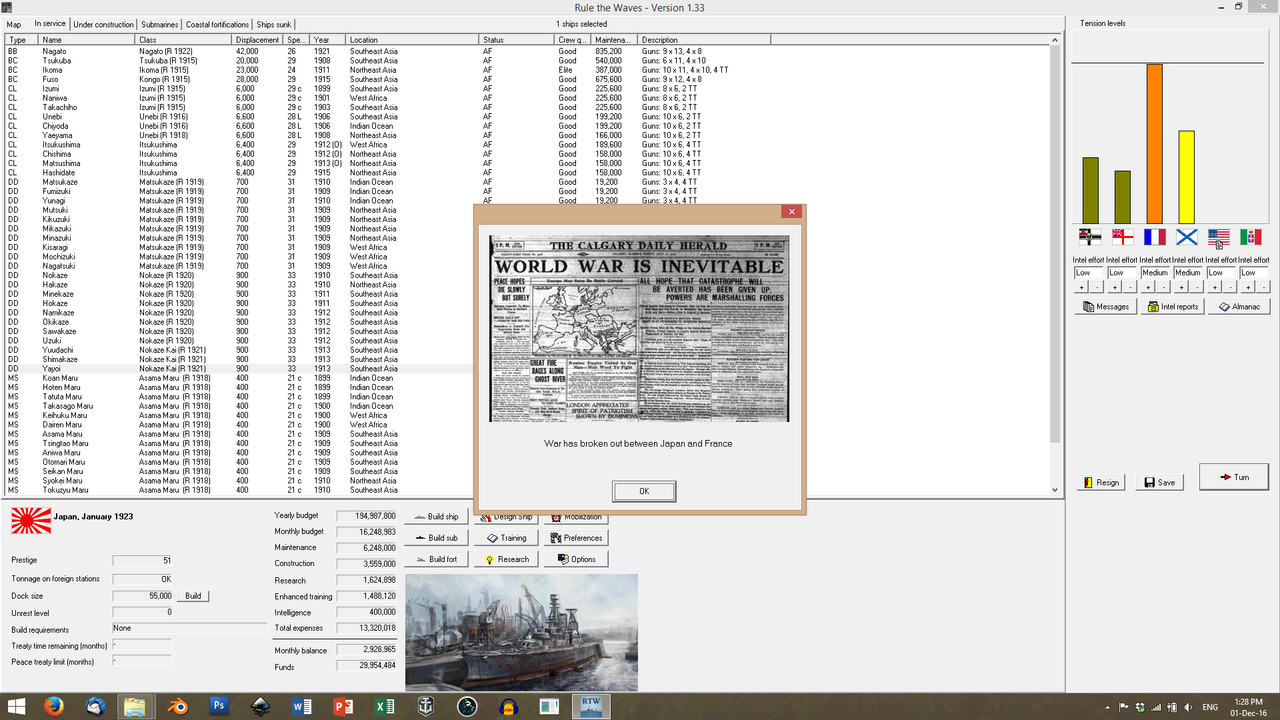

And so, things came apart shortly after the end of the year. On the 12th of January 1923, the French Ambassador delivered an ultimatum to Minister Kato; an ultimatum that was summarily rejected. France was now at war with America and Japan.

Poll

Poll