"It would be petty of me to not admit Vizeadmiral Büchsel's genius in not taking any chances

and succeeding in not losing the war in a nighttime ambush. His handling of the German battle-line was exceptional in Gotland; and I have no

doubts that his tactics won us the war."I am happy to say that, by the end of the battle, Herr Admiral

Büchsel and I were in full accord regarding the future of the Hochseeflotte

. The battleships were truly powerful weapons; but, for all their armor, they were surprisingly fragile against a single torpedo. If the German fleet were to take its place in the sun, we had to somehow address this matter - and we also had to make Herr von Tirpitz

and His Majesty see that a radical redesign of our capitals was in order"-Vizeadm. Galster K (post mort.) 1956, The Naval Question: Collected Papers and Letters, edited by Dr. Ernst Jablonka, Universitätsverlag Heidelberg.

Upon the return of the fleet, the Kaiser was quick to go public with statements regarding the

"final destruction of the Russian fleet" and the

"unquestioned supremacy of the Kaiserliche Marine". Most of the officers were glad for the praise; but they also were grimly aware of the fact that the latest sinking of the

Pamyat Azova, which the Kaiser was eager to attribute to his battleships, was, in fact, once again, the work of Galster's

Zerstörer.

For once, von Mecklenburg did not have to bring the two

Admiralität factions together. Both Tirpitz (under the strong prompting of Büchsel) and Galster had learned their lesson. Galster made the first move, approaching Tirpitz with his concerns regarding

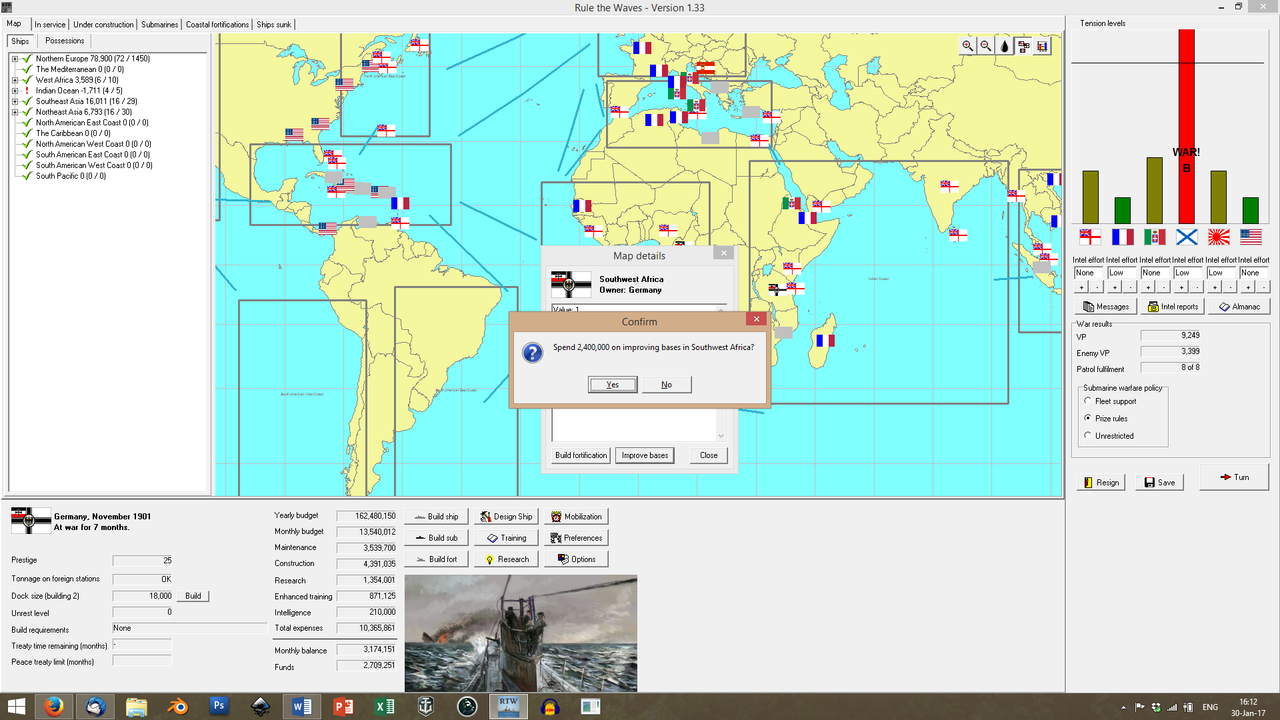

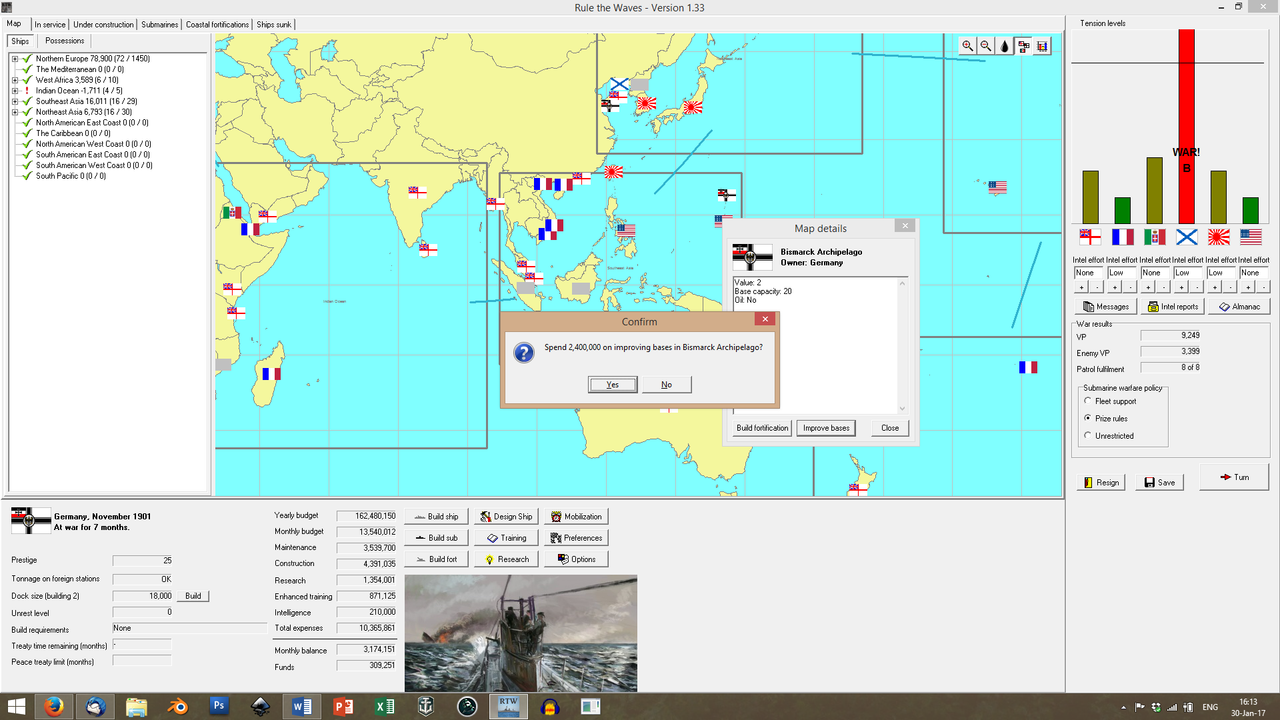

"the survivability of battleships in the modern battlefield against light forces and torpedo warfare" and with a detailed list of how Tirpitz' behemoths might be better fortified against torpedo attacks; Tirpitz, in turn, was quick to release further funds for the expansion of colonial harbors in Africa and the Pacific.

Finally the two admiralty factions were working to complement instead of undermine each other.

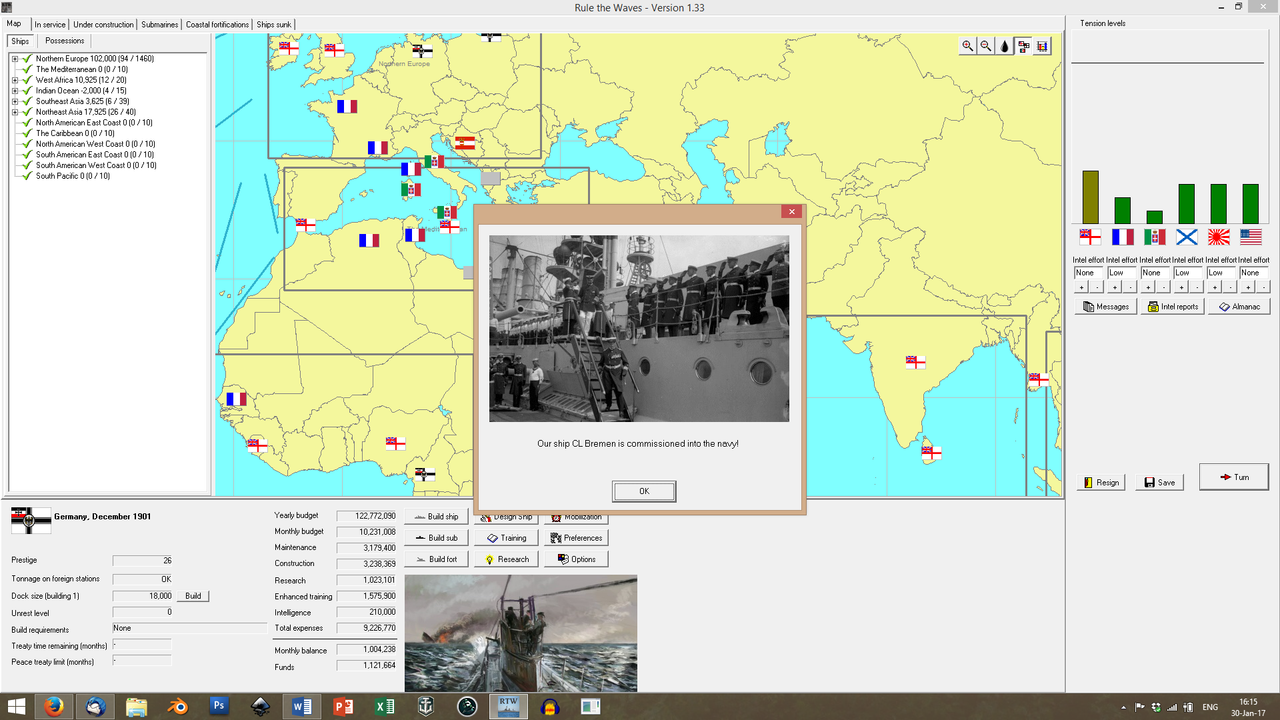

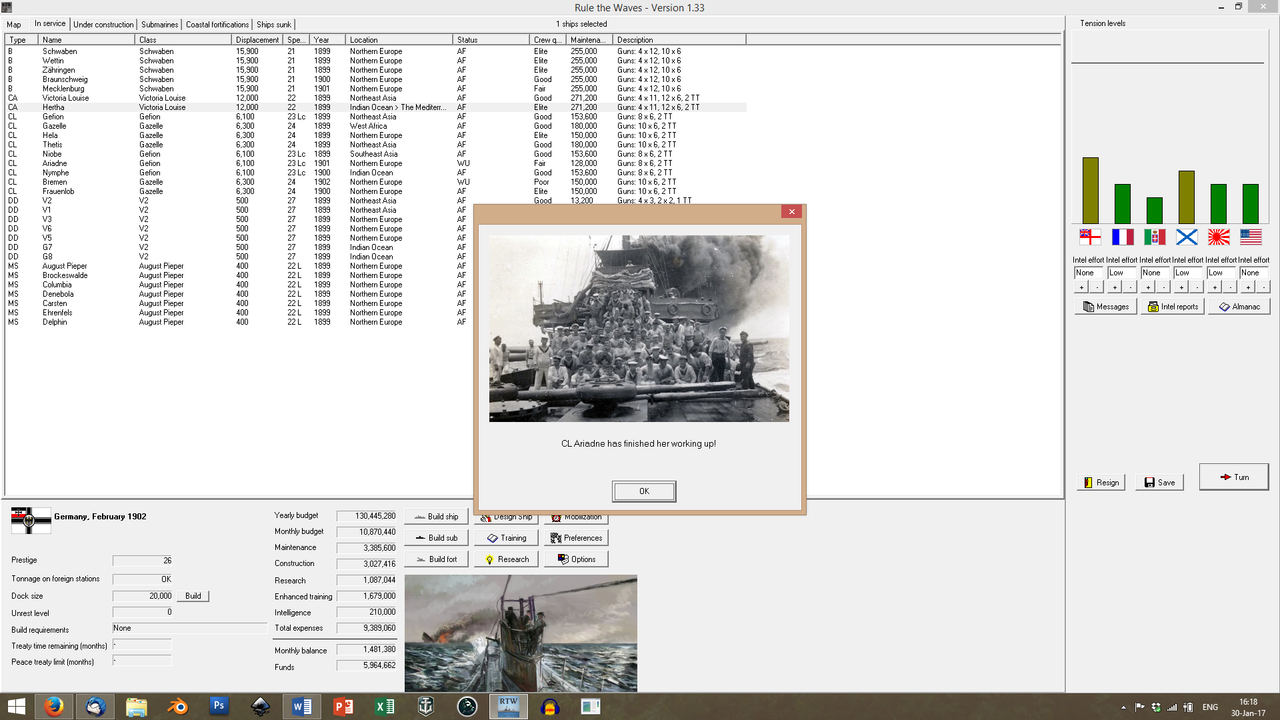

He also agreed on the need for new screening cruisers and authorised the accellerated completion of the light cruiser

Ariadne. The ship was commissioned on the 30th of November and Galster was very appreciative of the reinforcement of his cruiser forces. In collaboration with von Holtzendorff, he began drawing up a detailed, statistics-based plan for the interception of Russian raiders in the upcoming weeks.

Fortunately, it never became necessary to put their plan into action. On the 29th of November, Russia sued for peace: their ports blockaded and their armies in full retreat. The Kaiser requested the Navy's input and the

Admiralität was quick to proclaim that, with a few more months, they could park their ships in Finnish and Russian ports unopposed. The Kaiser was at the verge of demanding Russia's unconditional surrender, encouraged to no small degree by von Bülow - but then, von Mecklenburg pushed, and pushed

hard.

He arranged for the Kaiser to be invited to Mecklenburg, where the

Herzog's nephew,

Großherzog Friedrich Franz IV von Mecklenburg-Schwerin had recently come of age and assumed his ruling duties. He also arranged for the Kaiser to participate in one of the greatest deer-culling hunts of the last decade. Wilhelm, being a self-professed hunting enthusiast and constantly pampered by the von Meklenburg family, became particularly susceptible to the

Herzog's influence. By the end of the hunt, Wilhelm was perceiving the emissaries of von Bülow as constant annoyances; and was becoming increasingly receptive to von Mecklenburg's ideas.

The latter informed the Kaiser of 'conspiracies' in western Europe; of French and British plans to undermine German power, if the Russian bear were to collapse. The apparent balance of power in Europe had to be maintained, von Mecklenburg claimed, or France would come to Russia's aid, no matter their previous statements. Not to mention the danger of British involvement...

The Kaiser was incensed: both at the implication that German policies should be suggested by the approval or disapproval of the 'old enemies' and at the fact that von Bülow had failed to bring this to his attention.

"If all of my victories should be rendered void by a word of the British," he is said to have exclaimed,

"then should I mail my crown to Buckingham Palace and be done with it?"Von Mecklenburg's strength of personality once again saved the day. He opened up with a barrage of encouragement, declarations of fealty and appeal to sentimentality that would have made Bismarck blush; and followed with a proposed plan that seized the Kaiser's fancy. Once again, the Kaiser overruled his Chancellor's emissaries by appointing von Mecklenburg as his own personal representative to the peace talks; von Bülow could no longer ignore the increasingly relevant

Herzog. A silent war was to begin between the two; a war that would rage behind the scenes for the following year.

But for now, von Mecklenburg revealed his master plan. A peace was signed; a

very generous peace, the purpose of which was to, primarily, reassure the French and British and, secondly, lay the foundations of Germany's rise.

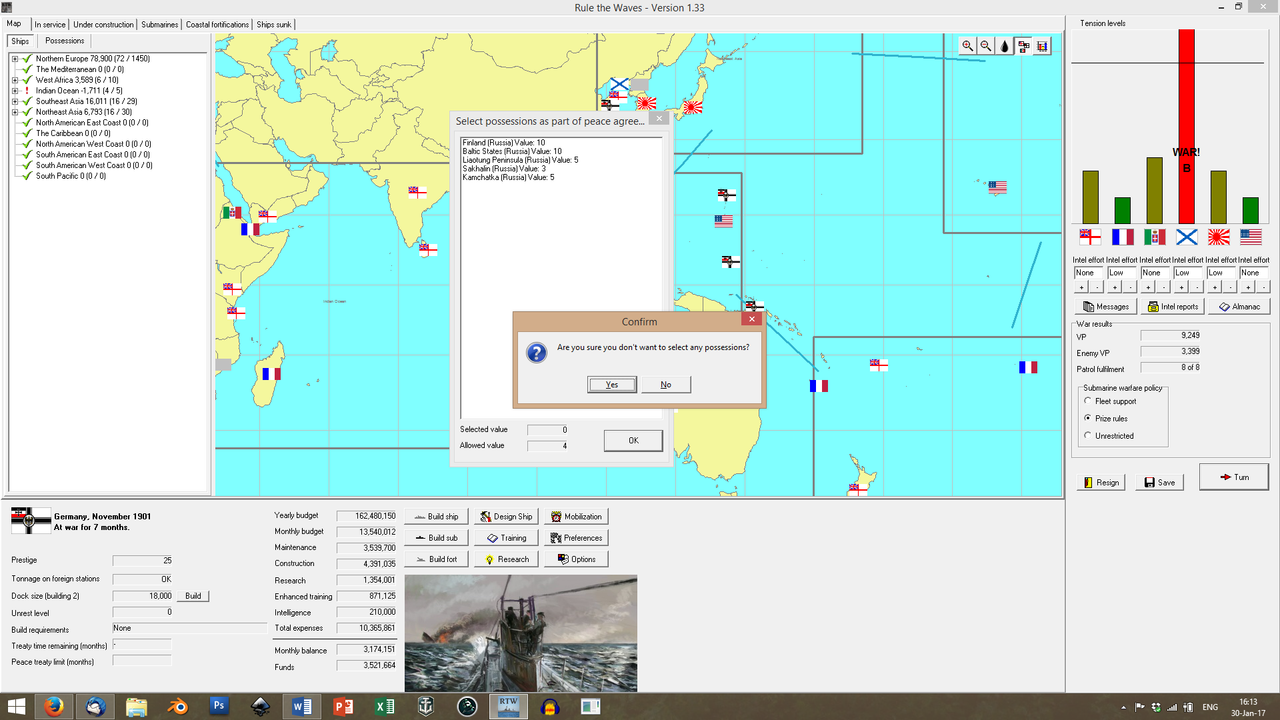

The Russians came to the table prepared to reluctantly yield some of their territories in the Far East - perhaps Sakhalin? They were stunned when von Mecklenburg informed them that Germany was completely uninterested in

any sort of territorial annexation. Instead, he negotiated for

trading deals and

resource exploitation. For the next

ten years Germany would receive tribute in the form of raw resources: coil, oil and ores from the massive stores of the Russian hinterland. No tolls would be in effect. German industrialists would be given access and the rights to select mining zones in Siberia - zones that the Russians were barely utilising anyway.

By mid-December, von Mecklenburg had the Russians tripping over themselves to sign the proposed peace; an arrangement that they considered a

bargain compared to what they had been expecting. What they failed to realise was that "Johnny's Danegeld", as the British press came to call the peace, would fuel a

massive wave of German industrialisation over the upcoming years.

The Kaiser sang von Mecklenburg's praise from the rooftops; von Bülow

seethed.

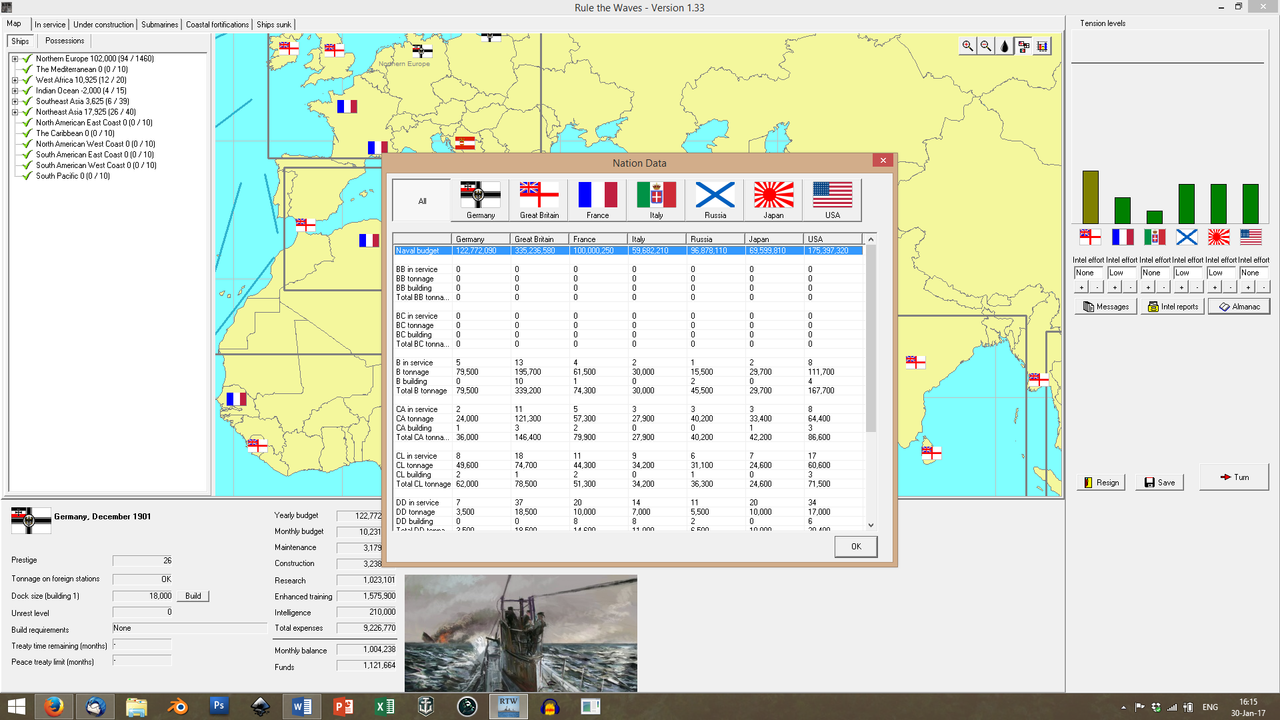

Sadly, any profits for the Germans were still in the not-so-near future. For now, the

Admiralität had to suffer a significant curtailing of their budget. Thankfully, they had been aware of that possibility and had accordingly limited their expenses: even after the signing of the peace treaty, they were still saving more than a million

Goldmarken monthly, for the time when they would be needed.

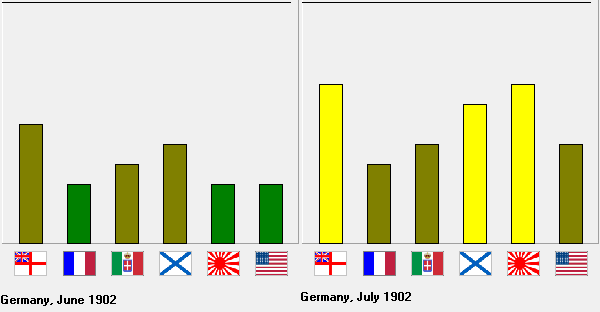

And, after all, their budget was nothing to be scoffed at. True, it was less than half of what the damned British spent on their ships, but it was more than the French! Or any other European power!

Christmas 1901: and there was much rejoicing! The new docks in Emden and Wilhelmshaven were completed and a massive victory celebration took place, with an impressive fireworks display organised by the

Admiralität. The Kaiser was throughly

gejubelt by the attending crowds, to his immense satisfaction.

.png)

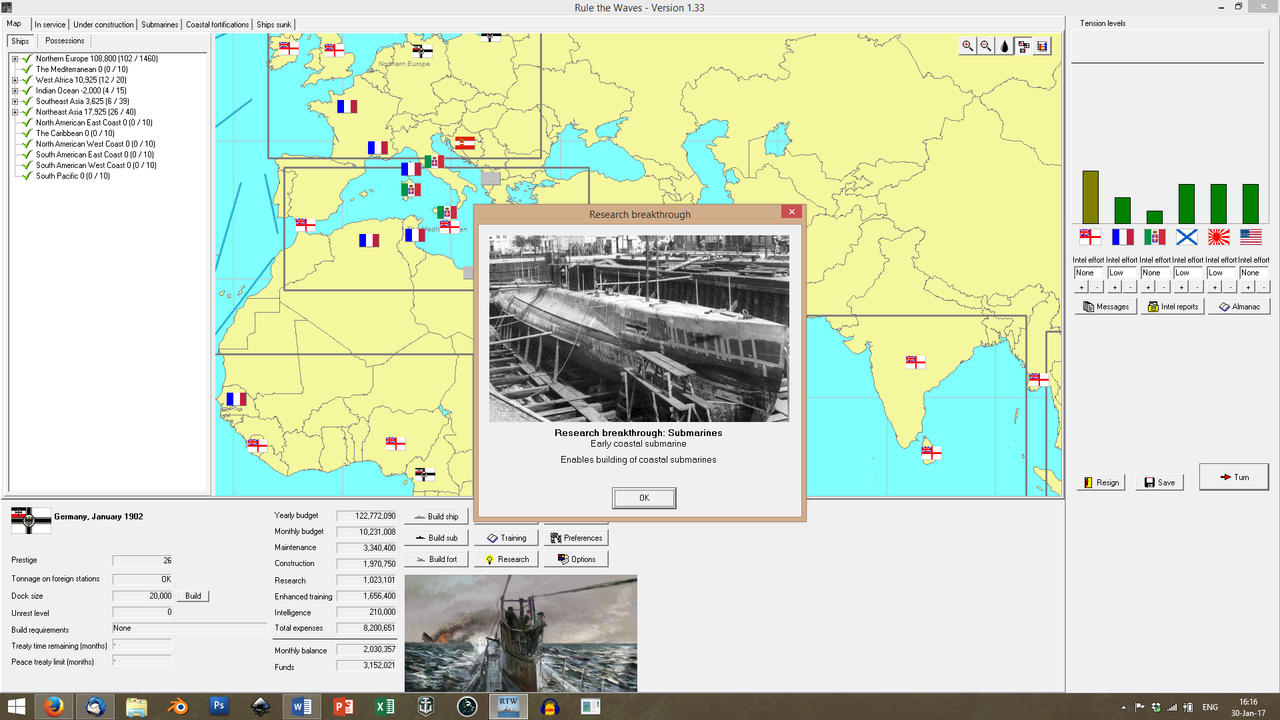

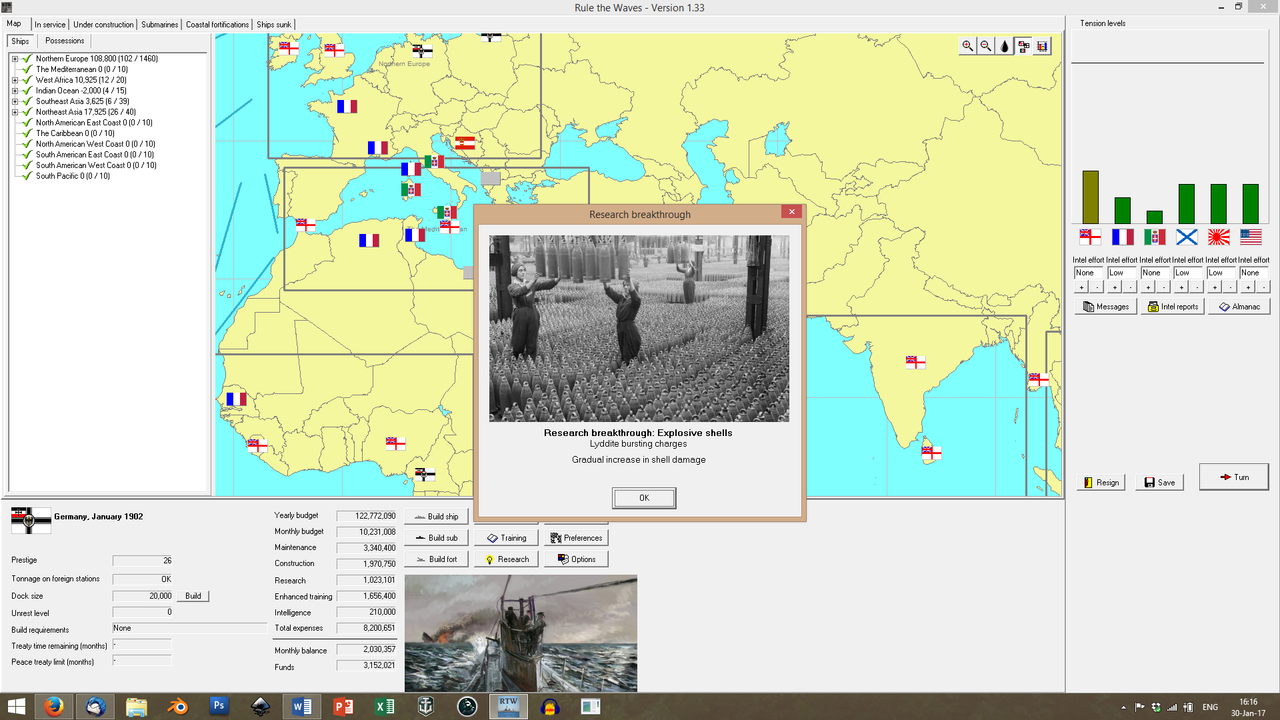

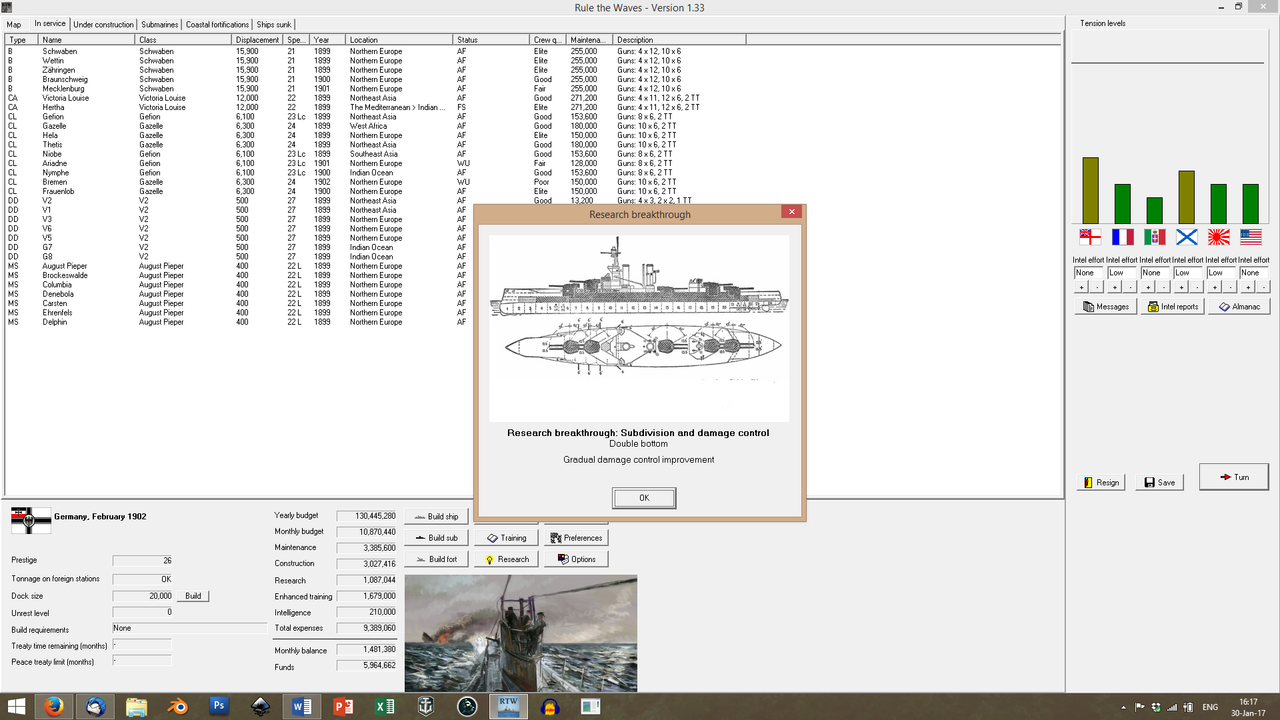

Also - research!

Finally fuelled by a joint Tirpitz - Galster push, the R & D department delivered to the grim satisfaction of both parties. First - the promised safety valves were rushed into production, ensuring that German machinery would be lighter and more reliable.

Then - to the palm-rubbing glee of Galster, a working prototype of a military submarine vessel, armed with torpedoes, was submitted for consideration of the admiralty.

And, following

that, improved, more destructive shells were introduced.

Finally, by February, designs for improved compartmentalisation were submitted. Both Tirpitz and Galster received those with barely-suppressed glee. Plans were drawn for the installation of 'bulges' and double bottoms on all German warships; the docks in the Baltic worked around the clock.

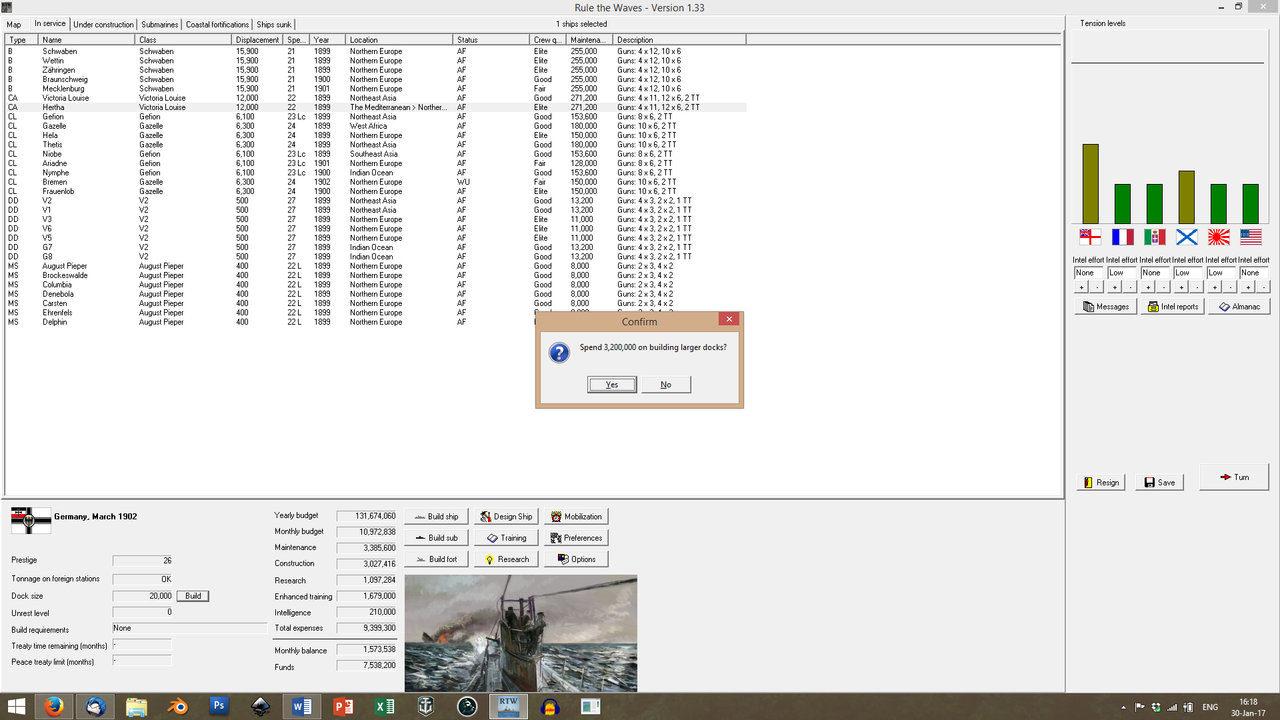

And the docks themselves were further expanded. Tirpitz expected to be able to lay down 22k-ton capital ships by March 1903.

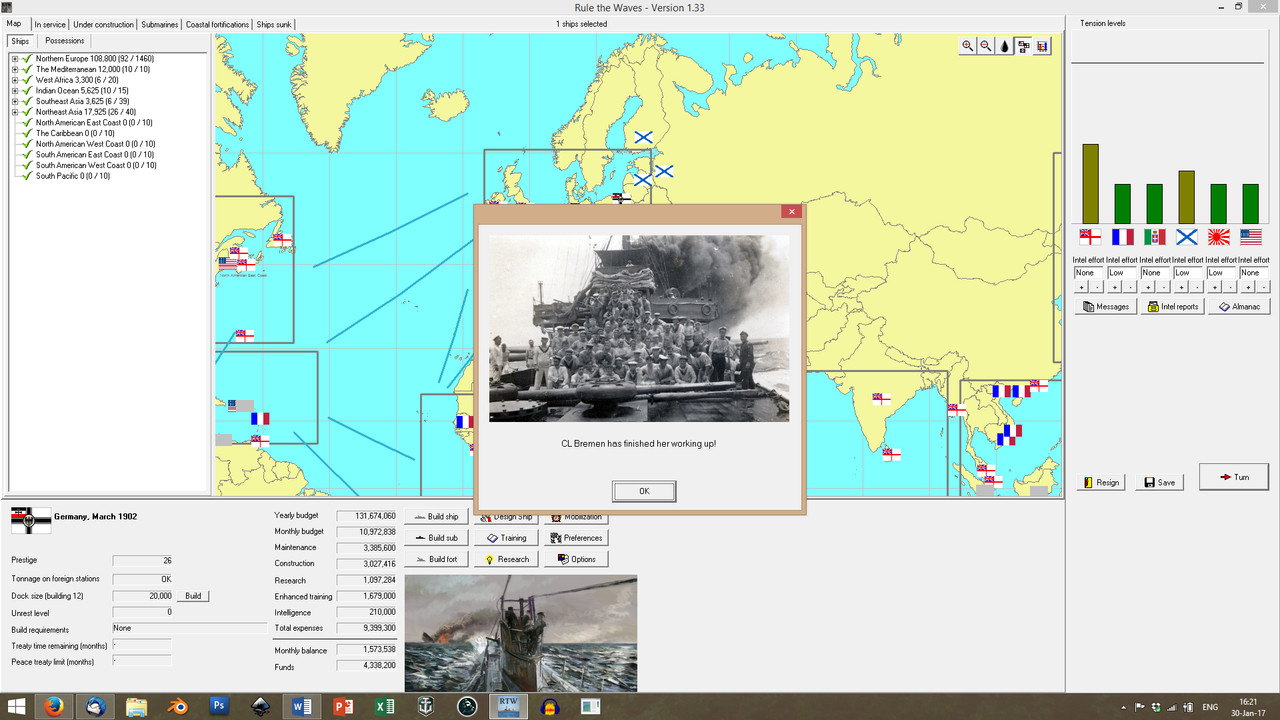

Meanwhile, Galster was busy with reworking his cruiser fleet.

Bremen and

Ariadne were commissioned and completed their shakedown cruises in early 1902.

So, when the Kaiser 'suggested' that a world cruise of a few German ships was in order, the

Admiralität was not averse to sending their newest ships out. The

Mecklenburg, escorted by the

Bremen and

Ariadne circumnavigated the world, in a mission to display the power of the

Kaiserliche Marine to all!

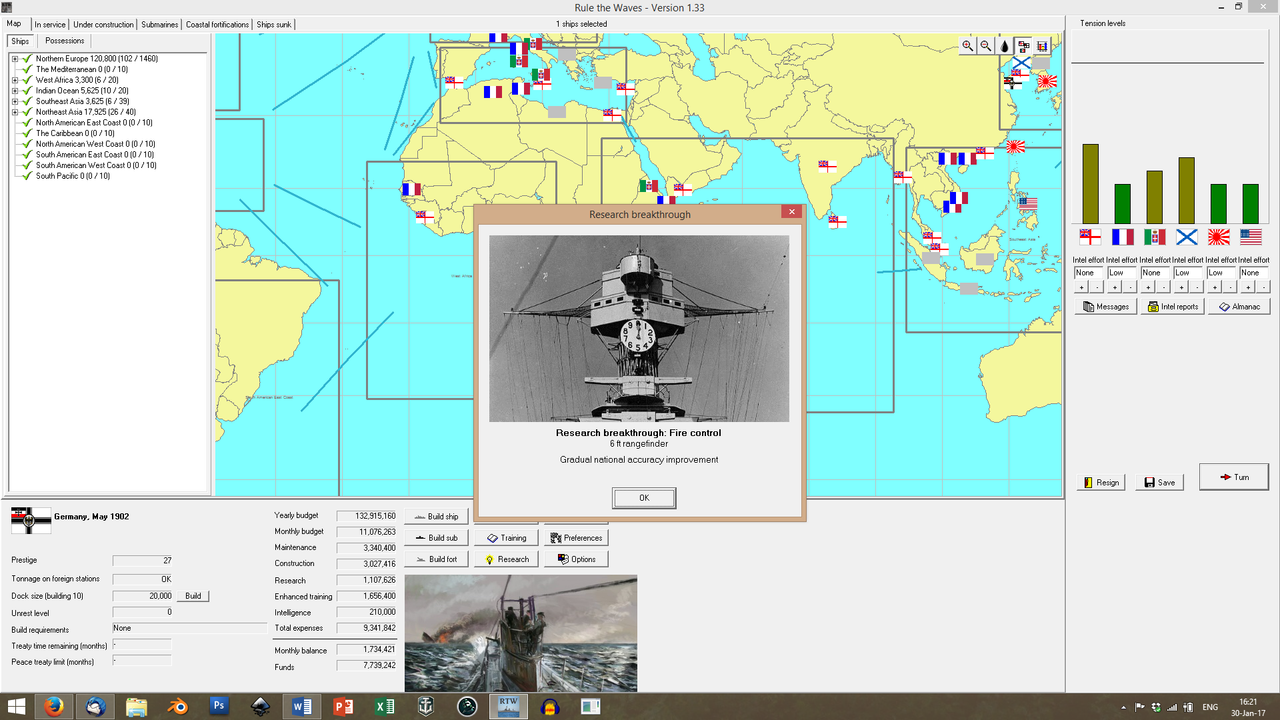

In May, Tirpitz unveiled the new R & D breakthrough that would make his giants more effective: massive, 6-ft rangefinders on their superstructures. Galster approved: anything to make the battleship more effective at keeping enemy cruisers away from the battle-line was a

good thing.

Also, to keep Galster happy...

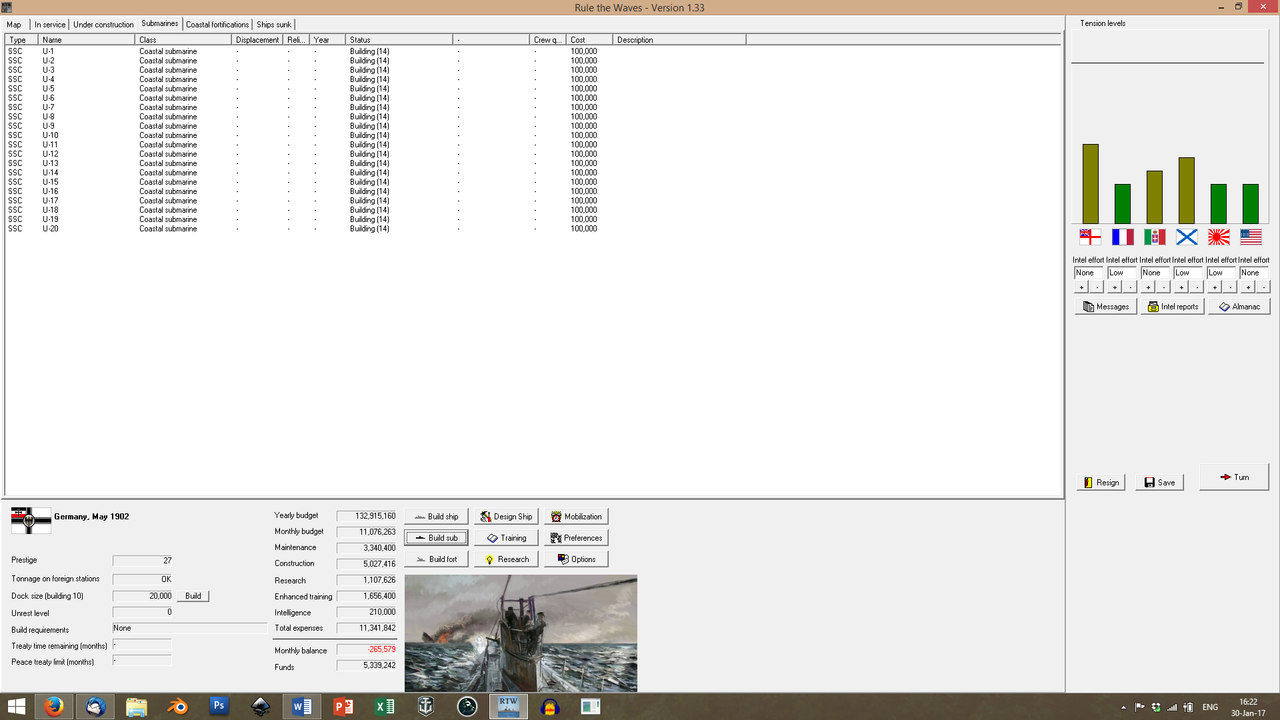

Ohoho. Hohoho.

Hohohohoho.

Hohohohoho.

But the laying down of the first German

Unterseeboote did not monopolise the

Admiralität's time in June. For von Bülow saw a great opportunity to strike back against von Mecklenburg in the home front. The administration of northern Korea collapsed in bloody revolution - and von Bülow knew that German forces were standing by in Tsingtao and Kiautchou bay. In what he perceived to be a daring move, von Bülow approached the Kaiser with a plan for the annexation of northern Korea; and Tirpitz, unfamiliar with the tangled diplomatic web of colonial politics saw no reason not to commit his forces. Von Mecklenburg, in a short family trip to a Swiss Alpine resort didn't find out about this until the orders had been sent out.

It is said that when news reached him, he was having dinner with friends; he paled and near-collapsed.

"In a few words," he is reported to have said,

"the Kaiser has undone all of my work of peace. There will be war again in less than a year and there is nothing I can do to stop it."

Meanwhile, the German expedition was successful; northern Korea quickly fell into German hands and one more Far Eastern base was secured. Of course, what von Bülow failed to realise was that Germany was not the only player in the international game; and that his little stunt had stirred a hornet's nest.